written in 2008 - excerpt from Raising The Bar

Were you fed through a bottle, or were you fed naturally?

Did you eat from plastic plates? Stand too close to the microwave?

Did you grow up in the ghetto?

Are you a recovering drug addict?

Is your life a living hell?

Are there things about yourself that you don’t like? Do you procrastinate?

Are you jealous?

Do you suffer from selfishness, obsessive behavior, mood swings, or low self-esteem?

Are you a loner?

Do you keep to yourself?

Or are you surrounded by so many people you aren’t sure which ones are your friends?

Do you have a support network to call on during hard times? I’m not talking about someone on the other end of the phone when you have a flat tire. I’m talking about someone you’d call when times are so hard that you don’t know if you’d be better off dead or alive. Do you know who’ll be there for you? Will you be there for yourself to make the right decisions based on what’s best for you? Or are your eyes swollen shut to what makes you happy?

I don’t know you, but I do know that we all have our demons. We all have our pasts that we don’t want to deal with, and we have things that we’d rather forget. If we didn’t have these things, we wouldn’t be alive. What I’m questioning here is whether you’re alive or just living.

Do your demons control you or do you control them?

Are you sure?

Let me tell you about a little boy who had demons of his own. His demons were no worse or better than yours, but his eyes remained shut tight to the effect they were having on his life. He used justification and blame, tried to prove his worth, and looked for respect, acceptance, and significance. These are basic human needs. We’ll fill them in; however, we can to gain what we’re seeking, even if it means living a life with blinders on.

This boy grew up with learning disabilities that were embarrassing. He was made fun of and excluded from most of the things that other kids get to experience growing up. Teasing was a daily occurrence, and he was filled with pain, guilt, and worthlessness. He didn’t develop physically because most of the time he spent on the playground was spent alone. He wasn’t invited to play neighborhood games with any of the other kids. Instead, he sat by a tree looking at cloud patterns. He tried to see what animals the clouds resembled, and he wondered if there was a heaven. He wondered what it would be like if there was. Would it be better than being alone most of the time? Or would he die and spend more time alone?

If he ever was invited to play, the games were miserable ones like ball tag. He was given the ball, tackled, and then beaten up. His childhood memories are filled with incidents like the times he was lassoed with a tetherball rope and then kicked and beaten. Things like this happened regularly.

One day, the neighborhood kids invited him to play baseball. He’ll remember that game for the rest of his life. He’d never played baseball before but was elated when they asked him to play. They said they needed one more to make the teams even, and he was more than willing to be a part of the game.

He was given a nice looking, leather catcher’s mitt. It was all beat up, smelled like oil, and felt great in his hand. He loved the smell of the leather and oil. The sun was out, and it was a great day. The kids all

got into position, and he was taught how to squat down and hold the mitt so the pitcher had a target to hit. They threw him a few practice pitches, and he caught them all. It felt really cool to have found something he seemed to be pretty good at.

After a few more practice tosses, the kids were ready to start the game. Right before the first pitch, the batter said, “You didn’t really think we wanted you to play, did you?” He swung the bat and smacked the kid right in the mouth, knocking his tooth out. The kid wasn’t even sure that he’d felt it, but there was blood everywhere. All he knew was that he had to get the hell out of there fast and get home.

When he made it home, he told his mother he’d taken the dog for a walk. He said that he’d started running, and the dog had dragged him across the street. He said that he’d tripped and smashed his tooth on the curb.

He spent the next few hours in the dentist’s chair having a partial tooth bonded to the half tooth that remained. Every few years, the bonding had to be redone. This served as a reminder. There was also a slight color difference between the bonded side and the original side. To this day, the tooth is symbolic of how the “stupid kid” of the neighborhood grew up—battered, beaten down, worthless, alone, and depressed with nothing to do but sit under a tree and wonder what was behind the overcast clouds.

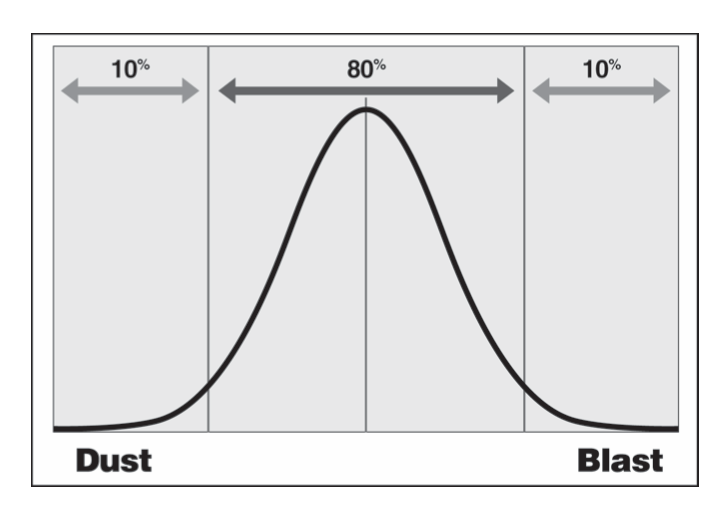

When the sun came out, his eyes were blinded to the beauty around him because his focus was on the future. His eyes were always looking up, but the sun burned them. When this happened, he lost hope, and the reality of depression pervaded his consciousness for yet another day. In time, he developed what he called a blast and dust scale.

For the little boy, dust meant doing nothing (depression), and blast was the hope for a better future (dreams). There was no middle ground for him. He was either blasting away at how great the future could be or sitting in the dust depressed about how badly his current situation sucked.

When he was eleven, his uncle gave him his first weight set. Almost immediately, he discovered that he didn’t need friends if he had his weights. He trained for four hours a day every day, and all he could think about was the next workout and how he’d be able to make himself bigger and stronger. The weights didn’t make fun of him. They didn’t exclude him, and they didn’t label him. He had control and could punish himself for all of his faults. He blasted with the weights and learned to disregard any negative remarks because they didn’t matter to his training.

His athletic ability improved with time, and while he still didn’t know the wrestling moves or football plays, he was able to kick the crap out of everyone who used to make fun of him. His outward demeanor changed. Outwardly, he adopted more of an aggressive “badass” look. He built a coat of armor to keep people away from him so he wouldn’t be beaten up or ridiculed anymore. He didn’t need friends or relationships. The weights gave him everything he needed. He only wanted to be left alone to build the strongest body possible.

The stronger he became, the less crap he took. No longer was he the “stupid learning disabled kid.” Now, people said, “Don’t mess with that guy because he looks like he could rip your head off.” Given these two options, he found the latter much more gratifying. It laid the groundworkk for the rest of his life. The “stupid kid” was gone. An imposing new persona emerged, wrapped in a suit of armor designed to keep people out and away. He found the significance and acceptance that he’d been seeking. The weights had saved him from a life of constant depression.

The harder he worked, the stronger he became, and the more attention he received for his size and strength. Both now exceeded those of men far older than he was. He’d decided what he wanted out of life, and training gave him the spirit to achieve things by being stronger.

This kid had never been asked to play Monopoly, Clue, Mouse Trap, or any other game because he’d been labeled as stupid. Now, he walked the halls of his school with authority and confidence. He’d become the master of his own domain. Friends, however, remained few and far between because he was still labeled as slow and stuck in special education classes. The kids in these classes weren’t from the same middle-class neighborhood in which he lived, so he wasn’t “allowed” to hang out with them. Time with them was limited to school or after-school activities like football and wrestling.

Wrestling became his passion because the team was comprised of kids who weren’t from his social class. Many were in his special education classes. The training was hard, individual, and intense. After having his ass kicked every day for a year, the weights came into the picture. Using his newfound strength, he didn’t lose a single match for two years. The boy had also started participating in powerlifting because he relished the competitive challenge of getting stronger.

He trained with a group of adults who took him under their collective wings and taught him proper training techniques. They showed him how to cycle his training programs for optimal results. As a result, he built himself into one of the strongest teenagers in the country, break- ing many state and national records in the process.

By contrast, he hated football with a passion. The coach called him slow and screamed at him for not knowing the plays. You needed to know the plays. You were also supposed to know what to do if a play was changed at the line. When that happened, you figured out what to do based on where the defender’s head went.

Not grasping this made the kid feel even more stupid. The coach was on his ass every day, and that made things infinitely worse. He always thought about quitting. His weight training sessions were the only thing helping him through this. He knew he’d be meeting his training partners in the gym after practice because there was always a meet coming up, and that feeling of anticipation temporarily made football tolerable.

On the blast and dust scale, wrestling and powerlifting were “blasting” and schoolwork and football were “dust.” He saw no reason to spend time with stuff that meant nothing to him. He wasn’t interested in anything that wasn’t enhancing his life. Schoolwork and football made him feel more like the “stupid kid” that the world had labeled him as. Wrestling and powerlifting showed him success and the ability to see that, if he worked hard, he got want he wanted. And what he’d wanted was for the abuse to stop.

There were eventually some decisions to be made. Weight training had added significant mass to his physique, and there were weight class issues to address. In football, he was a defensive end, but he didn’t have the speed to be a good pass rusher. He needed to add more weight to play defensive tackle, but this meant he’d have to wrestle as a super heavyweight, which he didn’t want to do. Wrestling all the fat guys took the fun out of the sport. To stay out of the super heavyweight class, he’d only have to drop ten pounds, so the decision was easy. He stopped playing the sport he hated and went with the sport he loved.

Powerlifting remained a constant, the way it would throughout his life. It went year-round and was always there.

This decision ate at him for weeks. The coach he considered the big- gest asshole of all sat down with him and showed him a letter detailingg the values and virtues of football. He told the boy that he cared. This was the most attention the coach had ever shown him, and the kid was in disbelief. Even so, he still just wanted this coach to go away. Every coach in the school had a word with the kid, trying like hell to get him to play football. They all had something to say, but not one of them listened.

Finally, he gave in to all their pressure and went back to playing football. He never wrestled again. He did what he promised to do with football, but powerlifting became his number one passion because it still fulfilled his needs and kept him away from what had hurt him. He was still a loner, but he was a strong one—by far the strongest in the school. A balance was struck—he kept to himself, and the rest of the world kept to itself.

His self-worth was measured under the bar. He built an increasingly stronger suit of armor to keep from being hurt and to prevent people from seeing him for what he truly felt he was—the stupid kid. This label never went away for him. The weights redefined it, retooling him into the “stupid kid who no one wanted to mess with.” He needed no one, and no one needed him. This was a perfect arrangement that kept the exterior pain away. The interior pain, however, never left him. It was suppressed and buried with half-truths and justifications.

He was getting stronger and spending less time in the dust phase. Most of his time was spent blasting. Training was the final piece that he’d needed to fill all the gaping voids in his life, and the goals that he’d set could now be fulfilled by him and him alone.

The selfish nature he developed became a safety net. Nobody messed with him, and he hid all his fears behind his strength, aggression, and intimidation. This was a way of life that could get him what he wanted without having to expose who and what he thought he was. Ironically enough, he’d found his greatest strength, acceptance, and significance in avoidance.

As an adult, he would give motivational seminars on what it took to be a better lifter. He’d show how to use these same qualities in life. The entire time, however, he knew that everything was a half-truth because he wasn’t happy with himself, and he couldn’t figure out why. When he was challenged, he always fell back on his basic model:

To avoid confusion, he threw one hundred percent of himself into everything, letting the rest fall where it would. He “fixed” his obsessive behavior by putting all of his effort into the gym—training for meets, going on diets, getting lean, or taking on some other drastic training goal.

To avoid confusion, he threw one hundred percent of himself into everything, letting the rest fall where it would. He “fixed” his obsessive behavior by putting all of his effort into the gym—training for meets, going on diets, getting lean, or taking on some other drastic training goal.

Meanwhile, the rest of his life was in the dust because overcoming non-gym related adversity took everything he had. He’d been giving his pursuit of happiness a Herculean effort, and he still hadn’t found it.

Blasting with everything he had left no time to focus on anything else. If something didn’t involve training, he relegated it to the dust pile and found something else to focus on. He called this “balance.” By placing one hundred percent of his focus on one thing and then the next, he stayed in blast mode constantly. He did this to seek pleasure and avoid pain.

This didn’t give him the pleasure he wanted, so he created new and bigger blast goals. He told himself, “If I could just get this...If I could just do that...In just one more year, I’ll be able to do this...” The obsession with these things never stopped, but happiness never came. He thought this was because he hadn’t yet achieved his ultimate goal—the one that would finally prove his worth for all time.

This was never about “the game.” To this day, this kid can’t tell you his sporting stats. If you ask him about his income and business statistics, he has to look them up. “The game” was never the point. It’s always been about proving something.

In adulthood, most people would say that he’s proven everyone from his youth wrong—that he’s no longer the “stupid kid” and that he’s become a very successful man. To him, however, there was always more to prove.

But to who?

Thirty years later, I now understand that I was blind to things that should have been important because I was trying to prove something to myself. What I didn’t realize was that this something didn’t need to be proved. It needed to be embraced. I was trying to prove something that couldn’t be proven in the first place. I was looking for the golden egg.

None of us can change the past. What we can do is look back and learn from our mistakes. One of the biggest mistakes I made was living my life according to the blast and dust scale. As my niece told me, this is analogous to living a life of heaven and hell. Life is what happens between the two.

When I take my scale and make a bell curve out of it, you’ll see the greater meaning:

My focus was on only twenty percent of what was going on in my life. According to the Pareto Principle, you receive eighty percent of your results from only twenty percent of the work that you put in. I felt that this was an acceptable way for me to live my life. However, if this rule is true, it applies to all the individual segments of the curve and not the entire curve as a whole.

So did I miss eighty percent of my life?

I ask myself these questions each and every day. Think of it this way. If you always drive to work the same way every day, do you notice the other cars on the road?

Do you see the new paint job on the old house around the corner?

Did you notice the river you crossed?

Or is getting in the car and turning on the ignition all you ever remember?

I was disassociated from a large part of my life.

Was it twenty percent? Eighty? Who knows?

That’s not the important part. The thing to remember about life is that it’s what happens between the bad times and the great times.

Eighty percent of life involves learning how to master what’s here at the moment. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t strive for things in the future or learn from the past, but you have to stop to smell the roses. I do that now. There’s an entire world out there right in front of your face. It’s not about what’s happened or what you strive to have. It’s about learning to love what you do have and finding happiness within yourself that’s not based on false justifications.

Staggering numbers of people fall to the far ends of this curve. They look for happiness in depression, drug use, alcohol, other people, work, over achievement, success, more money, status, and power. I’m not saying that this is right or wrong, and I’m not making judgments on whether it’s constructive or destructive. I’ve just found that there’s more to life than the things for which we strive. We need to stop and take a look.

Striving for big goals is essential. However, learning to find happiness in the process of achieving those goals is also necessary. Don’t let one goal consume your entire life. If you do, you’ll be living life the way I did. You’ll blast one hundred percent of the time, get burned out, do nothing, and just sit idle until it’s time to blast again. Trust me on this one. After living this way for thirty years, I can assure you that it will not bring you the happiness you’re seeking.

In my first book, Under the Bar, I tried to explain the values I’ve learned in the weight room and in sports. I know now that there were a few I missed. These values have always been there, but in looking back with an older, more experienced eye, I know there are ones that I’d overlooked, taken for granted, or just never understood at all. As coaches, athletes, and parents, we need to understand all the great things that sports offer. We need to see not only the values that fill our own gaps but the ones that build character, balance, and happiness.

1 Comment