Joel Fridman and I played with several models and arrangements for the 5-lift course. Our chief goal was to, at the same time, break strength into its multiple manifestations and their physiological differences, and introduce an integrated approach to it.

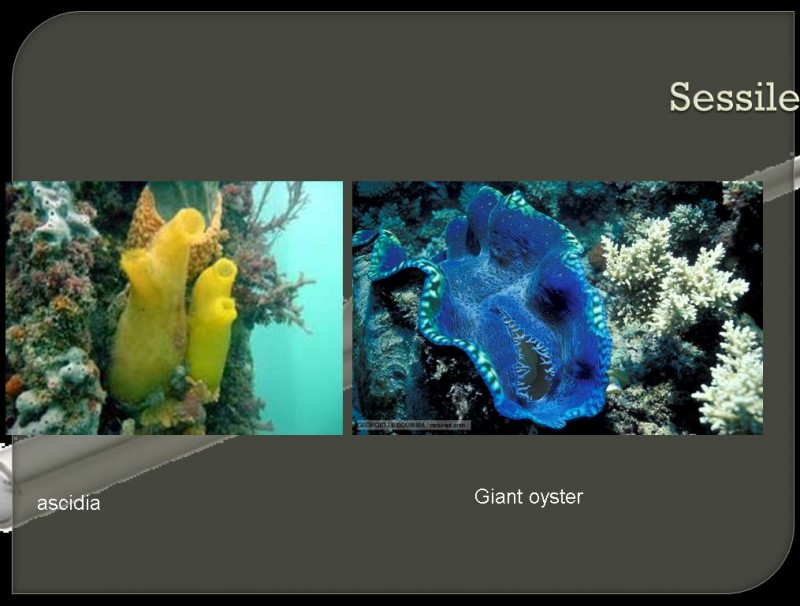

I was responsible for the introduction to the concepts of movement, strength (different authors’ typologies and also measurable strength components) and applied exercise physiology concepts. We were also strong on misconceptions such as those concerning exercise, training, fitness, conditioning, sport and physical activity. We were dealing with students who would receive a medical prescription with over 80% chance of containing a misconception. We had collections of medical notes prescribing “exercise”, “physical activity” or “sport” in synonymous and interchangeable manner and, unfortunately, college didn’t clarify that for them.

Joel was, if I remember well, a graduate from the second or third class of the highly innovative and experimental undergraduate track of “Sports Science” at the prestigious University of São Paulo. The classes of 1994 to 1996 attracted idealist students who wanted to either change the world through sports or change the world of sports through science. It ended up churning out frustrated and sad graduates into a market that was not prepared to assimilate them. Joel was my best work partner because all that wealth of critically thought ideas and contained innovation power in his head would burst into creativity at every opportunity. We were both anti-guru and anti-charlatan people (still are) and offered our students all the cited literature.

Right in the beginning, as I introduced the concept of movement through an evolutionary approach, there was a slide with a spider. That slide had to go as Joel strongly dislikes spiders and not just a few students shared his disgust.

While designing the conceptual part was challenging, the structure of the practical part was much more. Here were some of our questions:

- Should we introduce the lifts according to movement types? As in squat-press-pull? In this case, the lifts would be presented in this order: the squat, the bench press + overhead press, push press and push jerk, and finally the snatch, the clean and jerk, and the deadlift. We tried this with a small experimental group and it wasn’t that great. While the pedagogy of the Olympic weightlifts is optimally done in a segmented manner, the powerlifts are better introduced “holistically” (and later segmented into movement components).

- Should we introduce the dynamic lifts and the “static” lifts separately? Should we devote one day for the dynamic lifts and another day for the static lifts? We also tried that. It is practical but not optimal in terms of learning.

- Should we introduce the dynamic and the “static” lifts separately, technique only with an empty bar, on the first day and everything again on the second day adding weight to the bar and executing all the five lifts as full lifts?

The third approach produced the best results. We still speculate as to why. Joel suggested that the night between the very high-volume work with the empty bar from the first day somehow helped/forced a first level of assimilation. It’s important to point out that our students were not untrained subjects: as I mentioned before, most of them were coaches, were familiar with at least the powerlifts and many were also familiar with the Olympic lifts.

We expected the students to have more difficulty with the Olympic lifts. The big surprise was how technique-virgin they were in terms of the power lifts. The big “a-ha” moment for them was feeling their lats and glutes cramp during the bench press. At least 50% of all classes declared that “What I did before was not a bench press: this is a totally different movement”.

Keep tuned to the next chapters of this exciting story.

For my evidence-based column articles, click on my name and, in the author's page, choose articles: