It’s no secret that a lot of powerlifters are a little fucked in the head: you’ve gotta have at least some crazy in you to want to put a quarter ton of iron on your back and try to lift it. And hey, there’s nothing wrong with that – after all, a little crazy keeps life interesting.

But I think the connection between physical and mental health deserves a little more attention than that, and it’s not something that’s limited to powerlifting or even to strength sports. If you look at the broader fitness industry, there’s actually a lot of evidence of that same connection.

- Nearly one-third of people who suffer from long-term physical health problems also suffer from mental health problems. That’s not too surprising – just think about how stressful a minor injury can be, and then extrapolate the effects of a chronic condition.

- It’s worse in reverse: almost half of those with long-term mental health problems have physical health problems. Again, it’s not all that shocking when you consider that many people cope with anxiety and depression through emotional eating; or that those diseases make it more difficult to find the energy to exercise.

Even if you’re not dealing with a serious or long-term health problem, I bet you can think of a lot of ways that training can be stressful. I can, too, and so over the course of the year, I’m going to look at them in a little more detail.

One more thing. This is NOT a post saying you should stop trying because there're some misleading assholes out there. In fact, it's just the opposite. Check the vid below for more on that:

Gurus and Charlatans

Online programs are pretty popular right now (I have a couple myself). Turns out, they were pretty popular a hundred years or so ago, too. Back then, they were sold through the mail – you’d order by sending a letter to the guy (or girl) selling the course, and they’d send you your weekly training. Think Amish-style online training, or something like that.

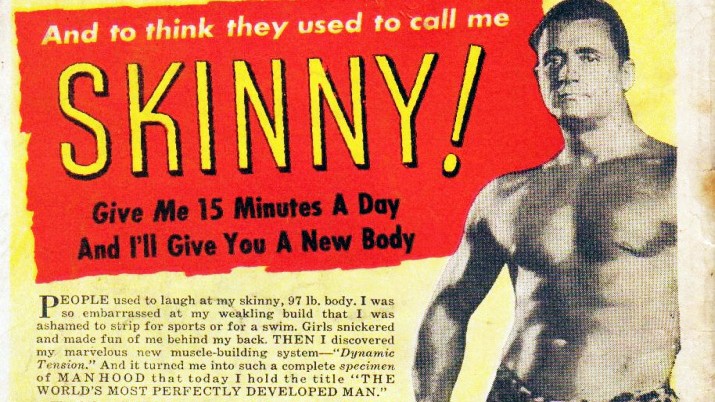

These mail-order muscle salesmen usually gave themselves a title, like Professor Smith, or World’s Greatest Something Or Other, to make them seem a bit more authoritative and help their advertisements stand out to everyone flipping through the pages of a magazine. And it worked – the second-best salesman was a guy named Earle Liederman, and his course brought in over a million dollars a year in revenue. You’ve probably heard of the number-one guy: his name was Charles Atlas.

Plenty of “gurus” sell programs today doing the same damn thing. They make up accolades and fancy website ads and bring in customers, even though it really only takes a few minutes of scrolling to figure out that the promises these courses are making could never come true. Who the fuck believes he’s going to add three inches to his arm or lose thirty pounds in a month? But people buy them anyway.

That’s because we desperately want to believe that there’s a guy out there with all the secrets: someone who can show us the ropes, and who has our back when things go wrong. This appeal to authority is actually a logical fallacy, but it’s a tempting one because human beings feel an emotional pressure to conform to groups – and to leaders of groups, like the guy writing the program. There’s a certain amount of comfort in believing that “if this smart guy says it, it must be true.”

Manipulative Marketing

All that would actually be fine if it weren’t for the fact that usually, the gurus (A) don’t actually have any special knowledge, and (B) are selling their programs using manipulative marketing. (A) isn’t really all that bad; maybe the program doesn’t work too well, and you’re out $20, but that’s not the end of the world.

(B) is much more destructive. Let’s go back to the guys selling their courses in the early 1900s. They weren’t just selling them by calling themselves professors and running around making up accolades. They were using ads that, basically, made people feel really shitty about themselves, and then claiming that their course could “cure” those shitty feelings.

Take a look at Atlas’s most famous ad (one of the longest-running print ads in American history):

You don’t want to be the 97-pound weakling, do you? Fuck no. That’s why you’d buy Atlas’s course.

It’s really no different today. Even if they’re not quite as obvious, ads of guys with photoshopped, chiseled abs and girls with perfect butts are very obviously implying that hey, you’d be happier if you looked like this. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not advocating body acceptance; I think that’s just twisting the message in an opposite, and equally unhealthy, direction. The point is that you shouldn’t make any judgements about yourself based on an advertisement – especially an ad designed to manipulate you into buying something.

But sadly, people do that exact thing all the time. It’s hard not to, when you’re constantly bombarded by the same messages over and over again. The cognitive dissonance alone can cause stress and anxiety. Hell, even I feel insecure sometimes looking at ads like these, and I’m doing pretty decently in the fitness world.

And studies show that the negative consequences can go even deeper: decreased self-esteem, poor body image, and increased prevalence of extreme diet or exercise habits all can result from repeated exposure to these types of messages. These outcomes are even more common in those who have suffered or are currently suffering from some form of eating or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

What to Do About It All

Look: people have been selling programs this way for over a hundred years. It’s not a fad. It’s not (just) a social media thing. It’s not going away. So forget about changing it, and start thinking about how to deal with it.

The first place to start is always awareness. When you’re hanging out on the couch watching The Biggest Loser and start to wonder why you don’t look like Jillian Michaels or Dolvett Quince, stop for ten freaking seconds and remember that first and foremost, they’re actors; and second, how they look has no bearing on how you should feel. Usually, taking those ten seconds to stop and step out of the storyline in your head is enough, and over the long term, it will start to make a real difference in your perspective.

Next time, we’ll look at how this all does play out on social media, and what that means for you.

1 Comment