The end and beginning of a Gregorian year is just an arbitrary date, like any other. It does, however, represent not only a symbolic but also a material landmark. In many parts of the world, that’s the end of the academic year. That’s when people graduate and the scary unknown of whatever comes next begins. Some insurance plans start in January, as well as other official activities. Suicide rates spike, since the period between right before Christmas and soon after New Year’s Day is considered “family time” — something hard for those who don’t have families or who have sad memories attached to them.

RECENT: The Squat Rack: The Heart of the Weight Room

In training terms, it might not mean much. For athletes, it may mean planning for the following competitive year. For many coaches, it means saying goodbye to some of their athletes who will move on to adult life. For personal trainers, it’s a pretty tough time, since many people take a break (and take a break from paying as well).

Most adult responsibilities and plans, however, don’t follow a 12-month cycle. Let me give you some examples:

- Pregnancy lasts around nine months. This time frame is not negotiable. Some health plans that cover pregnancy and delivery require an 18-month membership before the due date.

- Most college degrees in the USA are four years long.

- Most masters degrees are about two years long.

- Most PhD programs, if straight from college, are five to six years long.

- Most medical doctorates take four years to complete, like law doctorates and others.

- Mortgages last between 10 and 30 years.

Not surprisingly, the relationship people have with a sport also follows cycles. Some sports are highly determined by physical abilities that decline with age fast enough to cause retirement even before “stable adulthood” is reached. Others rely on physical capacities that decline slowly. Powerlifting is one of them, and it allows athletes to remain competitive for a long time.

The relationship with the sport may not be determined by physical decline, though. Especially if it is a team sport, many times life gets in the way. Many people who played college football, for example, will quit once they go to medical or law school, or their full-time jobs make it impossible to keep it even as a hobby.

The relationship with strength training and even strength sports is a bit different. Once a certain level of commitment is reached, usually as a stable adult, it frequently becomes part of that person’s identity if not forever, at least as long as the person is functional. This relationship is dynamic and changes through time. In this article I’ll share with you some of my adventures that culminated in 2017 and offer a few tools that may be useful for you.

Life Stages: They Are Not Just Imaginary

Life stages exist. The pioneers in the study of life stages focused on child development (Beilin 1992, Harris 1995, White et al 2010). For the last 30 years, however, scholars have been attempting to understand the stages of adult life. People live longer and the baby boomer generation entered middle age and now old age, contradicting the “retirement and death” expectation.

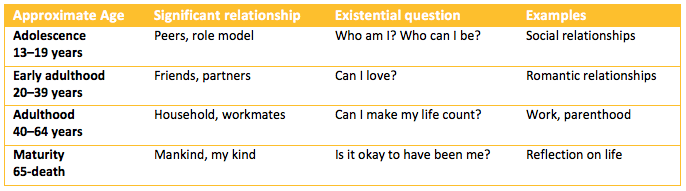

Erikson (1977) was one of the relevant authors to look at adulthood as a complex set of stages, but it was journalist Gail Sheehy (2011), in the 1990s who broke up modern adulthood into more realistic stages. As one of her interviewees, a nursing home director, said, in the 1970s he would see 40-year-old adults bringing their 60-year-old parents to the facility, whereas in the 1990s he was seeing 72-year-old adults bringing in their 90-year-old parents. Sheehy proposed the following stages:

Provisional Adulthood (18-30)

First Adulthood (30-45)

- “The Turbulent 30s’”

- “The Flourishing 40s”

Second Adulthood (45-85)

- “The Age Of Mastery (45-65)”

- “The Age Of Integrity (65-85 And Beyond)”

Now, that’s more likely for the brave new world. Around 30 is when things get real, babies and very young growing children are the chief concern, together with settling down professionally. It’s also when most sports and even training, if it wasn't an integral part of one's identity, are abandoned.

The 40s are a short period of some level of climax achievement for some individuals. And from there, one transitions into the “second life” or “second adulthood.” Not surprisingly, that’s when many people start new (and innovative) businesses and also pick up strength training.

In elite masters powerlifting competitions, you usually see two types of lifters: those who lifted their entire lives and those who discovered and fell in love with it in their early or mid-40s. I fall into the second class (and I’m 54). By my early 30s, I had a four-year-old, had defended my PhD dissertation, and was principal investigator in several research projects. By my early 40s, I was worn out, sick, disappointed, and lost. I realized I had spent all of the four previous stages with one huge background noise: getting over the fact that my central goal in life, which was improving it for the better through knowledge combined with rational and harmonious human relations, had been vampirized by opportunist radicals and/or wrongly channeled by me. All that, and the feeling that I hadn’t been the mother I expected myself to be. Hell, I didn’t even win the tooth brushing and veggie eating battles. Life had become a sequence of summer lice seasons and projects that excited me less and less.

It was around Sheehy’s predicted “new adulthood” beginning that my life went through a dramatic discontinuity in almost every relevant aspect. I handed my last report for my last public grant supported research at the university and didn’t renew my appointment, to many people’s dismay. I had hit the proverbial rock bottom and I needed a strategy out of it.

That was when strength training and powerlifting came into my life. Now, mind you, I did have a plan. Actually, a rough decennial plan. And I channeled the resources I already had—solid training in the hard, biological, and social sciences, writing skills, and experience in project management—into this new life. I re-educated myself, applied for a license as a strength coach (which, in Brazil, requires higher education in the field and is federally controlled), and was quickly invited to teach graduate courses, lecture, write, and coach. I published the first textbook on powerlifting in a Latin language, a 400-page book titled Back to Basics, and others. I broke a squat all-time record in 2011 and remained until 2015 in the first positions in the powerlfting world ranking, if not the very first. I’m still ranked among the (something) all-time best. Sheehy was right and it was the age of mastery: I did become one of the best in this thing I still don’t have a name for, which is the intersection between excellence in doing something and knowing something.

MORE: The Top Authors, Athlete Blogs, Coaching Blogs, Articles, and Products of 2017

I was in love and devoted to powerlifting and I had to find all possible ways of “giving back to the sport.” First, I designed a social project to address the needs of the vulnerable youth in impoverished areas. I trained at a gym in a slum in Sao Paulo and it made a lot of sense. Politicians and companies paid lip service compliments to the project and made promises they never kept after elections. Finally, the major federation that controlled that training center created obstacles. I gave up.

That was when people came up with the idea that a new national powerlifting organization was needed, one not fueled by corruption money and committed to a rule by law ethos. Lots of people were there for the first meeting — none remained. I managed to organize a few meets, which is something I soon discovered I hated. I examined the international sanctioning bodies available. I even became an international judge in three of them. At some point around 2013 or 2014 I concluded that, for historical reasons, organizing ethical sports in Latin America was virtually impossible.

Between 2012 and 2016 I created and taught a continued education program for coaches and other health professionals on strength and lifting. By 2015, it covered a wide range of topics in eight courses. In a certain way, again, I did it because there was nobody else to do it in Brazil. By then, I was more than twice a year in the USA to compete and judge. In 2015 I hit my best bench press and judged so many meets that I lost count. It felt to me that judging became, after all, my preferential way of “giving back” to the sport.

Meanwhile, I started working for elitefts. Decades of college teaching didn’t prepare me for that experience. The abstract idea that “sufficient and quality information produce better decision making” materialized before my eyes. I was giving, but to something bigger than “the sport.” Hold that thought.

The plan ended abruptly in 2015. That is when I moved to the United States. I know it sounds weird, but I didn’t know I was coming to stay. Life throws us some curve balls and that one was tough. I had to make up my mind: I applied for permanent residency based on the “exceptional ability and higher degree” provision and was approved. Actually, I was approved in this immigration status for two different fields, which is very rare. All in all, I was good. And then, according to the government as well, I was badass. Now it was just “live and let live.” Peace and love, right? Wrong.

Things Learned and Things to Let Go

My relationship with the sport of powerlifting changed dramatically in the year 2017. The following items build on what I described concerning life stages and also a few insights:

1. Competing

I competed once this past year. I had fun and was still the best by far among females. The year before, I was winning one specific federation world championship by over 50 kilograms or 110 pounds more than the second lifter in the open class when a hamstring tear brought me down. Except for the pain, it didn’t bother me. I realized that my relationship with competition was “off.” I had intrinsic motivators related to the process of preparing for one specific day where I could surrender and go for pure transcendence, but I also had extrinsic motivators related to my lifelong commitment to meritocracy and the respect for rules. I don’t feel the “social sharing” is completely real or satisfactory anymore. Not while being a federation official. It never was fully satisfactory, but now it’s gone. I also miss the transcendence element at the platform. I started to enjoy it more in complete solitude. A month ago, I had my final crash against systems that fail the meritocracy ideal and that is not negotiable for me. Will I compete again? I’m not sure. But I will never "give (back?)" to any sports organization again.

2. Giving Back or Passing On? — Pro Bono Work, Organizational Paradigms, and Guilt Trips

From the “peace and love” generation, I inherited the motto according to which “the love you take is equal to the love you gave.” In other words, or Gabe Sorenson’s words, “You take from powerlifting what you put into it.” What I learned from the past decennial plan is that giving back is different from passing on. Giving back is charity; you are grateful for what you have been granted and you give back what you can. Passing on includes improvement. That is how civilization was built — by passing on what you learned plus your original contribution.

Where I came from, and where amateur sport was either entirely corrupt or completely idealistic, the “elders” once had a sit down with me and said, “Look, for five years, your life will be miserable, your family will come second, you will lose money, your career will suffer, and your health will as well. It is your commitment to the sport. Beyond that, it is suicide.” I should have listened to them.

I’m done with trying to fix what is beyond my ability. In other words, I’m done with giving back. I’m passing on.

3. Coaching

I’ll keep this short and promise to expand it in another article. This year I worked more with patients, in collaboration with physicians, than athletes. Most of them were distance-only; until 2015, people either came to my place or were distance-only. I don’t handle gyms very well. Some thoughts:

- Online programming is always online coaching. Deal with it. It is also a highly qualified work. Nobody can do well online if they didn’t do well on-ground and master training concepts.

- Programming is always online for obvious reasons. You need to either choose a platform or build your own.

- You need to be online because the person you are coaching can be anywhere, and early signs of injury happen suddenly. You need to respond.

- You need to be creative with communication and information technologies to fix issues and teach technique. That includes creating individualized videos, video chatting while training in real time, using chalk, threads, video analysis software, and whatever else you can think of.

Most of my people did well, some got hurt. It’s life.

The Scientific Mindset and the Mysteries of Human Strength

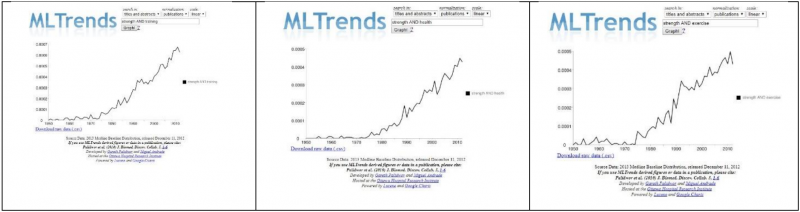

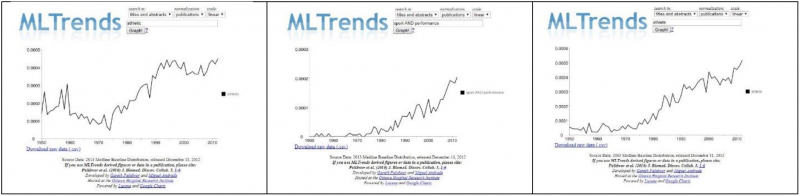

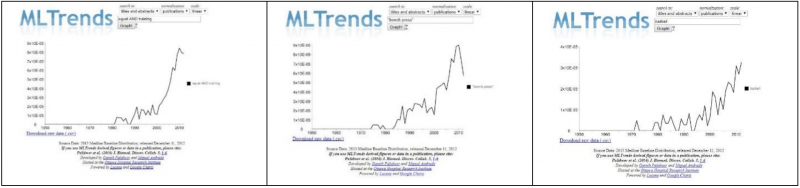

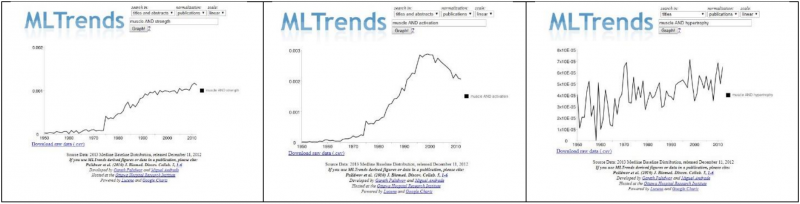

The good and the bad news is that many of the burning questions about strength are still unanswered. To begin with, there is no way around the fact that experimenting with humans with high levels of risk is unethical and animal models just get us so far. But the real good news is that there is more research about strength in general, both in absolute and relative terms. This is not an academic paper: in an academic paper you don’t leave the search system in the picture, but rather describe it. I’m hoping to encourage you to use these tools, so I’m leaving it “raw.” The images below were obtained from PubMed data normalized by the total number of indexed publications at each year.

Figure 1 suggests that strength is being studied in a broader perspective as well as specific (physiological, biomechanical, kinesiological in general) ones. The curves show a stable increase, with a steeper rise by the mid-1990s. Figure 2 shows there is much more and more traditional research on muscles and strength, but the trend is that of a stable or declining relative interest. Figure 3 shows that the scientific community has been more interested in sport in the past, and maybe the focus has changed during the decline of the Cold War. Figure 4 suggests that in spite of the small volume of research into the strength specific motor tasks and movements, it shows an interesting recent increasing trend.

Keep in mind that this is not a scientometric research, but a collection of trends that I compiled to back my claim that strength remains a scientifically attractive subject. That is reason to celebrate among us, educators. Don’t forget our elite motto: Live, Learn, Pass On. We’re here to educate, and we should be happy with our opportunities.

Figure 1: Scientific Production on Strength

Figure 1: 1a represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about strength and training; 1b represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about strength and health; 1c represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about strength and exercise.

Figure 2: Scientific Production on Muscles and Strength

Figure 2: 2a represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about muscle and strength; 2b represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about muscle and activation; 2c represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about muscle and hypertrophy.

Figure 2: 2a represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about muscle and strength; 2b represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about muscle and activation; 2c represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about muscle and hypertrophy.

Figure 3: Scientific Production on Sports

Figure 3: 3a represents the relative increase in indexed research publications containing the term “athletic” on titles and/or abstract; 3b represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about sport and performance; 3c represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about “athlete.”

Figure 4: Scientific Production on Movement-Specific Studies

Figure 4: 4a represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about squat and training; 4b represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about bench press and 4c represents the relative increase in indexed research publications about barbell.

What Now?

Very simple: keep living, learning, and passing on. That’s what elitefts is committed to. I stand by it.

References

- Harris, Judith Rich. "Where is the child's environment? A group socialization theory of development." Psychological review 102, no. 3 (1995): 458.

- White, Fiona Ann, Brett Kenneth Hayes, and David James Livesey. Developmental psychology: From infancy to adulthood. Pearson, 2010.

- Beilin, Harry. "Piaget's enduring contribution to developmental psychology." Developmental psychology 28, no. 2 (1992): 191.

- Erikson, Erik H. Life history and the historical moment: Diverse presentations. WW Norton & Company, 1977.

- Sheehy, Gail. New Passages: Mapping your life across time. Ballantine Books, 2011.