I don’t know about you, but I find it difficult to write my own training programs.

Even though I train other people for a living and have a decent understanding of proper strength and conditioning programming, I can’t seem to program for myself very well. The objective thought process that I use when programming for others goes out the door for some reason when it comes time to train myself.

I know a lot of coaches and trainees deal with this problem, so I have outlined three solutions that I have used in my own training to help you write better programs for yourself.

Remove Your Bias

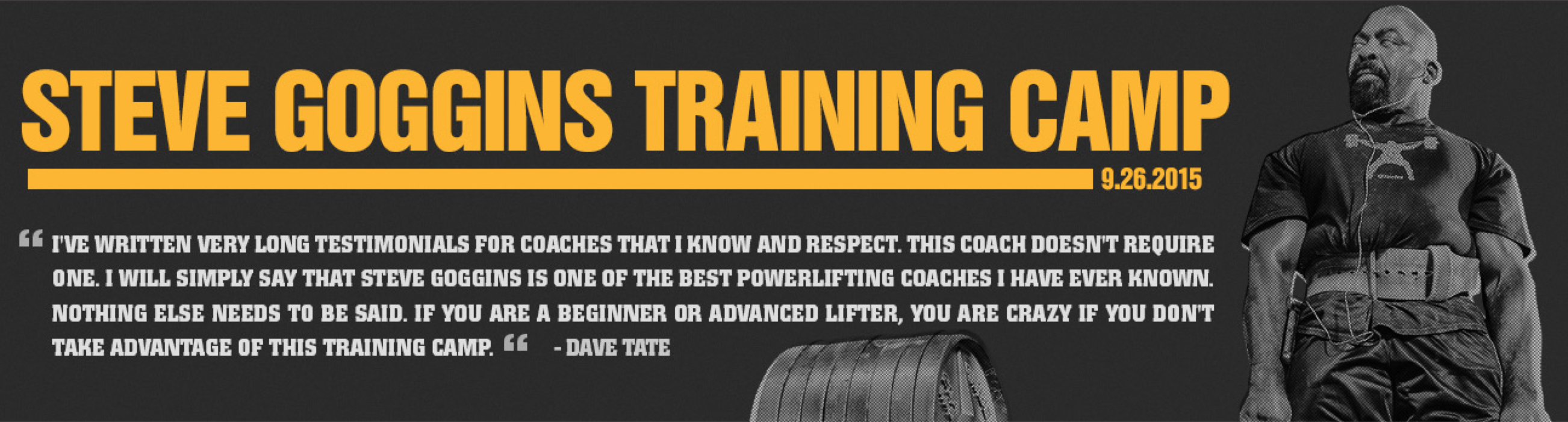

The easiest solution is to have an experienced training mentor or other qualified professional write your program for you.

It’s human nature to favor your strong points and conveniently neglect your weak links when you write your own programs. This is one of the many reasons why having a coach pays itself back several times over.

As an example, I recently had a colleague of mine review my strength program, and after looking over the program for a matter of 30 seconds, he determined I wasn’t doing enough horizontal pulling to accomplish my 600-pound deadlift goal.

WATCH How to Design An Annual Programming for Powerlifting — Weeks 1-5 After A Meet

This was a shock, as I thought I had been doing enough, but my clouded vision prevented me from seeing this.

That same colleague took me through a brief assessment and saw my left glute was significantly more inhibited than my right due to a very tight left hip flexor. This was something I had noticed, especially as my deadlift numbers went higher and higher, but I never put in the time to actually correct it.

He gave me a few corrective exercises that have contributed greatly to clearing up my movement issues and making my deadlifts feel a lot better.

Your own bias can be the biggest factor holding you back from success.

I highly recommend taking the time, and making the investment, to have a professional that you respect evaluate what you are currently doing. I guarantee you will come away with some valuable insights that you may not have seen on your own. Even if they don’t write you a full-on program, a few tweaks here and there are sometimes all that is needed to get you over the hump.

Don’t Fret Over the Exercises

The first thing most people tend to do when they sit down to write a program is figure out what exercises they are going to perform. This sounds logical, right?

Well, as Alwyn Cosgrove has pointed out several times in his works, exercise selection is the least important programming variable1.

Instead, the repetitions, sets, rest intervals, and lift tempos need to be planned out before you decide what exercise you’re going to do. We adapt much faster to a particular rep scheme, rather than to a certain movement1.

So the next time you sit down to write out your next 4-6 week block, decide what training effect you are going after (I’m assuming you want to build strength, but what kind? Speed-strength? Absolute strength?) and incorporate the set and rep scheme that will set you up for success with that goal.

Even though a lot of you reading are powerlifters and the movement variety isn’t that great to begin with, it would still do you good to put the emphasis on the “other” training variables before you decide you are going to do X, Y, and Z exercise.

To put it in perspective, it doesn’t matter if you do deadlifts for three reps at 30% 1RM if your goal is max strength.

The deadlifts don’t make the program; how you perform those deadlifts is what makes the program.

Keep A Training Log

This is probably the single-most powerful practice that I have used throughout my training career. When I keep a training log, I am consistent and my numbers go up.

When I don’t keep one, I have a much greater tendency to skip the gym and my numbers, of course, are stagnant or they decrease. Not only that, but weeks and months can pass and I will have absolutely no clue how I got from Point A to Point B if I don’t record my progress.

You have probably heard of the statistics that talk about those who write their goals down on paper have a much higher success rate than those who don’t2. I think the same is true with training.

If you write down what you are going to do, there is a much greater chance of it actually happening.

For me, I know this is especially true when squat day rolls around. Being that I am much more proficient with the deadlift, I don’t like squats as much. If something happens during the day that throws off my training schedule, and I don’t have that day’s session written out, it’s not happening.

I would love to sit here and say that I never miss a day no matter what, but that’s just not true.

However, it is much more true when I have a training log that basically says, “You have to do this.”

The big misconception with training logs is that you have to write down a ton of stuff. You don’t. Write down the movement, the sets/reps, tempo, and even the rest, and jot down notes where you see fit. If something felt great, make note of it. Maybe you slept better the night before or had something different for breakfast. A training log helps you identify certain trends that may be occurring that you would not have picked up on, otherwise.

If you want to look how you did six months or a year ago, it’s essential to have those notes to refer back to in order to figure out what you did to look that way. Without the notes, you are shooting an arrow in the dark.

This is why it is important to actually go back and review your log every few months to make sure you are accomplishing what you are after. And I’m not sure what it is, but seeing my own notes helps me remove that “denial” aspect that many of us carry.

Yeah, I do my mobility work all the time.

Sure, I cycle my sumo deadlifts every three to four weeks to keep my adductors from hating life.

Well, the training log will tell you if you are actually doing these things!

While the concept of a training log may not be directly related to writing out a better program, it does the priceless job of helping you actually execute said program. You can have an amazing program on paper, but it won’t increase your lifts on its own. You have to show up. And a training log ensures you do that.

Conclusion

The ability to put together a smart, objective training program for yourself that gets results over the long-haul is an oft-overlooked skill, and one that I am still working to master.

However, by letting an experienced professional evaluate your program, focusing more on the “numbers” behind an exercise, and keeping a training log, you can have a program that does just that!

References

1 Cosgrove, Alwyn. Results Fitness Program Design Manual.

2 Matthews, Gail. Goals Research Summary. Dominican University. http://cdn.sidsavara.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/researchsummary2.pdf

2 Comments