In this country, we have a bad habit of excess. We always think more is better, but in reality, more is just more. Just because you’re doing more doesn’t mean you’re doing anything that’s actually better for you. In all actuality, you’re probably just pounding unnecessary stress on top of the necessary stress for adaptation.

At some point in time, you’re just unnecessarily taxing the CNS. Ever heard of something called overuse injuries? When you add junk volume on top of planned stressors is when problems arise. This is why I do my best to avoid overuse and overtaxing my athletes whenever I can. How do I do this? Well, it’s by managing my sessions with my athletes and cutting the fat out of my programs. Let me explain.

RECENT: Comfort Zones are Death Zones

Someone once told me when it came to programming, their objective was to be able to get as much bang for your buck as possible. In essence, throwing one grenade and doing as much damage with that one grenade as possible. This stuck with me. For example, I look at my programming from a zoomed-out week. I don’t try to fit everything into one day; I try to fit everything into the week that I believe is best for my athletes.

That helps tremendously as I’ve seen people make the mistake of trying to do it all in one day. Most of us try to get a 2:1 pull to push ratio in our programming. I save time by doing this over the course of a week versus cramming it into one day. Why? Because:

- I want quality;

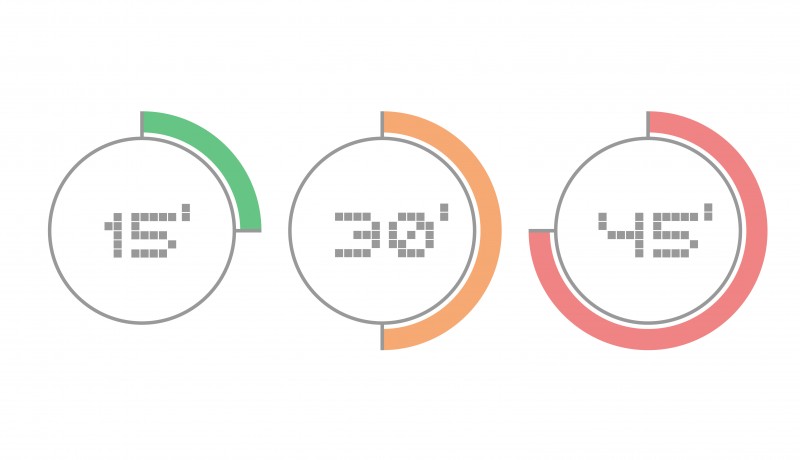

- And I don’t want an athlete in my weight room for more than 45 minutes.

I have found this is the time when things start to head south in training. On top of that, I like my tempo to be fast-paced. Now, the argument against this train of thought would be, “You get what you demand,” and to that, I say, “Good luck with your three-hour-long sessions.”

By spreading volume out over the course of a week I am allowed to train more efficiently and get more out of my max effort lifts. You have to keep in mind I go max effort, dynamic effort, and repetition effort every day on a three-day split. This is very taxing. But I’ve been able to do this without destroying my athletes by choosing the most efficient and effective exercises within the day. If you look at my programs, you would be hard-pressed to find an imbalance in the programming. I mean, it’s not just my love of comic books that get me all the Thanos comparisons.

Rafael Torres Castaño © 123rf.com

Now, the next thing some may think is, “There is no way you get all that work done and have a balanced program in 45 minutes.” Let me stop you really fast and say that I don’t mean “balanced” as in there’s a perfect ratio to everything (my post-chain definitely runs dominant). All I mean is that the program makes sense. But back to the Domino’s Pizza Time lifts.

When you look at the tempo I have in my lifts, I have very dense programming. My max effort block is usually paired with an antagonist and a prehab. When we go into dynamic effort, we could be anywhere from 14 x 2-3 to 10 x 2-3, and the rest time for these is anywhere between 30 to 45 seconds. Theoretically, I can get this work done in five to seven minutes. I usually take more time for my max effort work, but I don’t put my rest time on a stopwatch.

When my kids are ready to eat, I let them go hunt. I’ve often found if you hold them back too long and have them wait to rest, they end up becoming lethargic. As soon as my kids are primed, I let them go to the next set. Mental capacity is huge with max effort work. I’m not going to give you enough time to psych yourself out.

When we go into our repetition effort work, the tempo is usually already going from our rep effort work. I don’t want hesitant athletes; I want aggressive ones. I let them go at a fast tempo but give them time to get quality reps in on their accessory work. Their max effort is also slowed down for this purpose. Dynamic effort is always quality speed/movement, but at the same time, I give them movements they can’t mess up. Keep it simple, stupid. We pick things up, push things away from us, and pull things toward us. There’s not much to mess up.

RELATED: So You Want to Be A Collegiate Strength Coach: The Pros

The time I do slow things down is when I work on my pure speed work outside on the field. I make sure there is adequate time for rest and recovery because I want pure speed work when we go out to the field — not conditioning. I want quality in everything we do. Taking time for recovery out there on the field isn’t soft; it’s smart. Even with my conditioning, I make sure we have more than adequate time to recover because at the end of the day, it’s not worth an athlete’s life, and they’re going to feel that value on their CNS regardless.

Now, my fieldwork may only be 45 minutes, and some of you are wondering how that’s even possible. Easy. I have an all-encompassing warm-up that only takes five minutes that’s grounded in movement prep. I don’t waste time breaking certain things into drills. I put them in my warm-up and coach them.

I do very basic tech work because, at the end of the day, I’m not training Usain Bolt; I’m trying to make non-Olympic sprinters just a little bit better at sprint mechanics. I am not Charlie Francis, and I won’t ever be; therefore, I admit that I am not going to be the one to turn an athlete into the next Ben Johnson.

When it comes to increasing the motor and high CNS sprint work, I keep it extremely simple. We run fast and recover, then we run fast again and recover some more — about 25 to 30 seconds between reps and one-and-a-half to two minutes between sets. If they need more time between reps or sets, I give it to them.

My change of direction stuff is pretty simple. We go from closed to open (reaction) to competitive. Joe Walker told me in 2015 (I’m paraphrasing here) that doing all the COD tech work might be a big waste of time. Again, I’m paraphrasing, but then I realized that he was pretty much dead-on.

I can sit there and teach you the perfect shin angle for a 5-10-5 for six weeks and then pat myself on the back that your time increased (thinking it was all because my ingenious tech work), or I can be real and admit to myself your time probably increased because we’ve run the drill 30 times by the time we tested it. Cognition and awareness are big things when it comes to running the drills. The quarterback that get’s better at hitting a wide receiver on a dig route probably has practiced throwing the dig to a wide receiver. It’s not because of the banded external and internal rotations he’s been doing.

In conclusion, I really just have become more efficient as time goes on with my programming. I quit wasting time on the things that don’t matter, and I make the focus on the priority. I’m no genius for doing it. In fact, I’ve only been able to come to this light bulb moment of realization by making so many mistakes. But after I’ve over-volumized athletes and saw adverse results, I realized that less (but more efficient/effective) is always more. More is truly just more.

Let me open by saying I've learned a ton from your articles and I love the family and growth perspective you bring as a contributor!

Question -- why only 1.5 minutes rest periods for sprints? Are these just sprint starts or actual 20 meter + sprints? To me 1.5mins seems like nowhere near the amount of rest needed for speed adaptations.