This article aims not to revisit what smarter people than me say about the core but rather create a simple and effective system to plan and train the core of an athlete. This system has to be simple to be understood by athletes and transferable to all sports.

My Vision of the Core Concept

Conventionally, the core is defined by a complex of muscles that support the lumbopelvic hip complex to stabilize the spine, pelvis, and kinetic chain during functional movements (Greenwood, 2007). To this definition, there is something I would like to add. In the core concept, I would like to include ALL the muscles that stabilize the shoulder and pelvic girdle with the spine to create a fixed point and allow movement. I won't go into details of the anatomy, but I want to talk about sport and movement. For every movement, we need a fixed point. Without a fixed point, our muscles can't produce strong and powerful movements nor perform the given sport.

A Look on the Sport Side

In sport, the core has two functions; safety and force transmissions. The safety function is to prevent placing our structure in susceptible anatomical positions and avoid injury. The second function is force transfer. A famous quote from Charles Poliquin says, "You can't shoot a cannon out of a canoe." The meaning of this in a strength and power action context is that stability must precede force production (P W Hodges, 1998). In other words, if you cannot stabilize the shoulder and the pelvic girdle with your core muscles, you will not have a stable base from which to produce or transfer power.

Let me illustrate with two examples. Firstly, to throw a ball with your hand, you need to stabilize the shoulder girdle with the spin and the pelvic girdle to build a fixed point to produce a powerful movement. As another example, if you want to tackle an opponent in rugby, you push through the floor with your lower body and the opponent with your shoulder. To limit the strength dispersion between the lower and upper body, and limit the deformation of your body, you need to create an inflexible link between the pelvic and shoulder girdle (with your spine between both) via your core. In my opinion, working the core is not only your six-pack muscles; it includes many more muscles.

RECENT: Why Athletes Should Use Cheat Reps

Both examples allow me to present the concept of anti-movement. Popularized per Mike Boyle (Boyle, 2016), anti-movement is another approach to core action during sport. Take all sports movements and let me know if you can see an abdominal or a lateral (oblique) flexing in any. Apart from some wrestling situations in contact sports, there are none. In the majority of sport actions, the role of the core muscles is to resist movement and preserve stability. From this observation, we can rethink core training by training them in an anti-movement approach to be more specific for the sports activity.

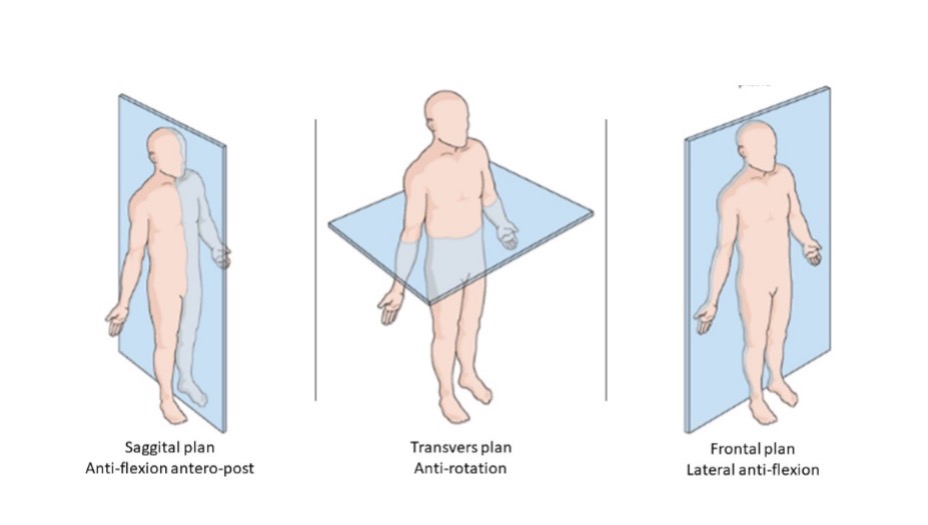

Commonly, we can define three basic anti-movement patterns. All the other core anti-movements will be resulting from these three basic patterns.

- Anti-flexion and extension antero-post (sagittal plane): Maintain the spine and the hips against force from the front or back. A good example is a situation when you lift something or someone with your arms.

- Anti-flexion lateral (frontal plane): Maintain the spine and the hips against forces coming from the side. When you carry your shopping bag with one arm on the side or when you change direction at high speed.

- Anti-rotation (transvers plane): Maintains the alignment between the pelvic and shoulder girdles thus preventing spinal rotation. It’s present in all the rotational movements and in all movements in which you push or pull something with one arm.

To be thorough, we can add anti-compression, call it anaconda strength per Coach Dan John. It is defined per the ability to "squeezing everything out to hold everything in place." We talk about inter abdominal pressure to create a stiff system, exactly like a tackle in American football or rugby. In a lot of sports, core activation occurs against external resistance. When that happens, you cannot anticipate. You have to adapt immediately, which will be essential for training and building our blueprint.

Creating a Blueprint

We see that there are four basic anti-movement patterns for the core. We have to build a simple system to organize and structure a progression to train these patterns for our athletes.

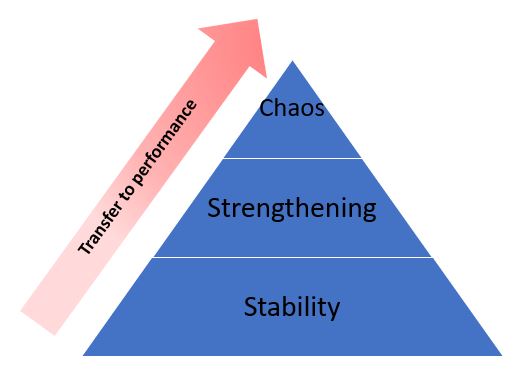

I suggest dividing the core training into three phases that I will call: Stability, strengthening, and chaos. Let me define each phase in detail.

Stability: The first problem with athletes is motor control. We start by teaching how to achieve a neutral spine and hip position. They need to experiment with lots of feedback and simple situations to improve their motor control. I will use a static isometric first, followed by an eccentric tempo during this phase. The goal is to expose the athlete to lots of volume with low intensity and no chaos because intensity and chaos can lead to a bad position.

Strengthening: Increasing the intensity of the exercise. The goal is to strengthen all of the muscles used in the exercise. There are two parts to this phase. Firstly, I increase the intensity of the eccentric tempo. There are two goals with an eccentric tempo. It will improve the strength of the muscles used and teach the athlete how to absorb force without form deformation. I like to teach the core muscle how to brake fast against resistance for the second part. For that, I will use isometric pauses. I will start with two isometric pauses inside the movement with a progressive speed increase between each pause. Then I move on to only one pause to improve the speed (and the kinetic energy) before the braking phase. And to finish, I will use the drop and catch method to improve the speed and the strength of the break.

Chaos: The last phase for core performance is transferability to sport. The goal is to create stability in unpredictable environments. For this to happen, I like to prevent the athlete from anticipating and force the core to react via reflex. I have created exercises where the athlete is focused on the result and therefore can't stay focalized on form (like in sport). Various tools are available to achieve this: Max reps for time, max speed or watts (power monitoring tools will be needed), eyes closed, random partner pressure, objects with random resistance like waterbags or plate suspended with bands, etc.

| Phase | Goals | Methods |

| Stabilization | Motor control | Static isometric; low intensity eccentric |

| Strengthening | Strength | Medium to high-intensity eccentric; Pyramidal concentric, pauses isometric; drop and catch |

| Chaos | Sport transfer | Rep for time; max watts or speed production (need power monitoring tool); closed eyes; random partner push; random resistance tools (water bag; plate suspend with band) |

To resume, the base for my core training is stability because without mastering this phase, it can lead to injury (athletes with the best core performance but injured are useless in sport). Even if the stability phase doesn't have a big impact on the sport performance, it must be the foundation of your core training. Note: You don't need to spend too much time on this phase. Just be sure that your athlete has effective motor control to maintain a safe spine and hip position. Once your athlete has developed an effective motor control, you can focus on the strengthening and chaos phase, which has the biggest transfer to sport performance. We win with the strengthening and chaos training, but we can lose without good stability."

Organizing Core Training

To structure core training, we have to think of two aspects—which training ratio between each anti-movement and each training modality.

To determine the different training ratios between each anti-movement, you need to analyze your athlete's sport, the position that he and she plays, and the number of workouts per week.

Analyzing the athlete's sport will give you the answer on which anti-movement you need to prioritize. For example, if you train a rugby player who has a lot of scrum, tackle, and wrestling situations, maybe he/she needs more anti-compression and anti-rotation, more so than anti-flexion lateral. So in the weekly plan, he/she will have two core workouts, one in which he/she will train the lateral anti-flexion only and the two above anti-movement twice a week. If you train sprinters, maybe they need less anti-compression work. Another way is to try to address the athlete's weakness.

Note: Heavy squats and deadlifts can maybe enter the category of anti-compression.

Knowing how to apply each training modality depends on your athlete's level, sport, and vision of plannification. Personally, if I work with a novice athlete in a development phase, I will follow a linear plan. They will perform a stability block with progressive overload until they can master all the anti-movement, a strengthening block to improve their strength, and a block of chaos for transferability to their sport. It's a simple construction, but with this model, you can't miss the link with the construction of your athlete's core.

For advanced athletes, it will be a little bit different depending on how your athlete's sport is organized (if it's like an Olympic sport in which you have to perform once or twice a year). Otherwise, I think you can follow a block system for the novice athlete. If you train for a sport with a lot of competitions in the year (like most team sports), I like to use a rotation of the modality each week or every two weeks. Be careful. Using a rotation of modalities means your athlete can adapt and better understand the difference between each one.

Example of a three-week block using a rotational training modality:

| Anti-Rotation | Anti-Flexion Lateral | Anti-Flexion Antero-Post | |

| Week 1 | Stability | Strengthening | Chaos |

| Week 2 | Strengthening | Chaos | Stability |

| Week 3 | Chaos | Stability | Strengthening |

Variety is Key

The last section in the athlete's core blueprint is how often the exercise is changed.

Learn to change because it's a key to adaptation and as I wrote above, the goal of your core muscles is to adapt to the unpredictable situation in a random environment. By changing regularly, you force your body to adapt every time. The negative side of variation is you don't have the time to master an exercise that requires a lot of stabilization work to limit the risk of injury.

Similar to the training modality, I think it depends on your athlete's level and experience with specific core training. If your athlete has a robust background in core training, it will be more beneficial to use a lot of movement variation. For professional athletes, I use the same movements for a block, but with the training modality rotating every week. With this system, I can maintain a base of execution for each movement, but the modification of the training modality provides variation, and they are forced to adapt.

This is an example that I use with my athletes. The base exercise remains the same and variety is created by changing the training modality.

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | |

| Anti-Rotation | Pallof press isometric 3x15" | Pallof press + squat 3x5 4010 | Pallof press + squat with plate swing 3x5 |

Exercise Bank

In this section, I will give you an example of a full core training progression for the three anti-movements.

Anti-Rotation

Stability

- Plank Shoulder Tap: 3 sets x 5 reps, hold 1" (isometric)

Progression: Knees to feet; hand under shoulder to hand wider than shoulder

2. Landmine Rotation: 3 sets x 5 reps, tempo 4010 (light eccentric)

Progression: Lunge position to stand up

Strengthening

- Stand Up Landmine Rotation: 3 pyramidal sets 1x10 1x8 1x6, go heavier at each set (pyramidal concentric)

- Landmine Rotation with 2 isometric pauses: 3 sets x 5 reps

Chaos

1. Landmine Rotation Rep for Time: 3 sets x 5 reps with max speed (use stopwatch to boost your athlete)

2. Landmine Rotation Drop and Catch : 3 sets x 5 reps

3. Rotation with Water Bag: 3 sets x 5 reps with max speed (use stopwatch to boost your athlete)

Anti-flexion Antero-Post

Stability

- Bird Dog Isometric : 3 sets 15’’

- Bird Dog with Movement: 3 sets x 5 reps with 1’’ pause

Progression: Start with hand and knees in quadrupedic position to start with hand and knees already standing (improve lever arm) and finally add a band.

3. Ab Wheel : 3 sets x 5 reps 4010 with band assistance (under your knees) or only body weight

Strengthening

- Ab Wheel with Plate on the Back: 3 pyramidal sets 1x10 1x8 1x6, go heavier with each set (pyramidal concentric)

- Ab Wheel : 3 sets x 3 reps 4010 (heavy eccentric) by increasing your arm lever

Progression: Start on feet and fall on the knees then on the feet with bent arms. Finish with a start on the feet and straight arms.

3. Ab Wheel with 2 isometric pauses : 3 sets x 5 reps

Chaos

- Ab Wheel Rep for Time: 3 sets x 10 reps with max speed (use stop watch to boost your athlete)

2. Ab Wheel Drop and Catch (Jump) : 3 sets x 5 reps

Anti-Flexion Lateral

Stability

- Side Plank Isometric : 3 sets 15’’

- Side Plank with Movement: 3 sets x 5 reps with 1’’ pause

Progression: Do all the movement with the arm on the hips

3. Squat with Shifted Bar : 3 sets x 5 reps 4010

Strengthening

- Squat with Shifted Bar: 3 pyramidal sets 1x10 1x8 1x6 go heavyer at each set (pyramidal concentric)

- Squat with Shifted Bar with 2 isometric pauses : 3 sets 5 reps

Chaos

- Squat with Shifted Bar Drop and Catch: 3 sets x 5 reps

2. Squat with Shifted Bar with Plate Suspended on Band : 3 sets x 5 reps

3. Squat with Shifted Bar with Eyes Closed : 3 sets x 5 reps

To Go Further

Two points to conclude this article.

I like to add some specific hip series work too. My goal is to eliminate weaknesses. I like to use adductor, abductor, psoas, and straight leg plank exercises. Most often these exercises are performed unilaterally and follow the same blueprint as core exercises (stability, strengthening, and chaos progression).

The second point is, I don't talk about aesthetics. My point of view is only in regard to sport. If you train for your physique, it can be a good approach to maintain a safe spine, but I'm not sure this is the best approach to hypertrophy your six-pack.

Final Thought

I often like to say, "Putting a Porsche motor into a cheaper car body isn't safe. When you improve your strength, power, and speed, you have to build a core to support all these constraints." This will help your athlete to perform and reduce the occurrence of injury.

References

- Boyle, M. (2016). New Fonctionnal Training for Sport 2nd étition. Human Kinetic.

- Greenwood, M. D. (2007). Core Training: Stabilizing the Confusion. Strength and Conditioning Journal ·, Volume 29, Number 2, pages 10–25.

- P W Hodges, C. A. (1998). Delayed postural contraction of transversus abdominis in low back pain associated with movement of the lower limb. Journal of spinal disorders, 46-56.

- Purves, A. (2007). Neurosciences. De Boeck.

Romain Guerin is a French strength and conditioning coach for professional rugby. He worked with the under 16 France team rugby league, rugby league academy, and police special forces. Romain earned his master's degree in sport science and other certifications like Westside Barbell® Special Strength Certificate and EXOS® certification. He can be reached at romainguerin.coachsport@gmail.com. Follow him on Instagram @romainguerin_pro.

I don't remember the author but for the average joe I'd also add in vacuums since every single one of my past and present clients have cared about how slim their stomach looked and working the TVA is inherently good for anaconda strength.

Thanks for writing!