Everyone has seen the athlete who struggles with upper body pressing movements. When they overhead press, their arms tend to travel forward while their lower back sways in. Or, if they are simply just standing there, you notice their caved posture leading to several dysfunctions in the shoulder. As an athletic trainer and strength coach in both the private and collegiate setting, I have seen countless compensations of the upper body lead to injury when not addressed. As strength coaches, what do we do about it? What CAN we do about it? Performing some simple range of motion (ROM) screens can help determine what the issue actually is, that way we can train for what we are trying to achieve.

Quick Anatomy Lesson

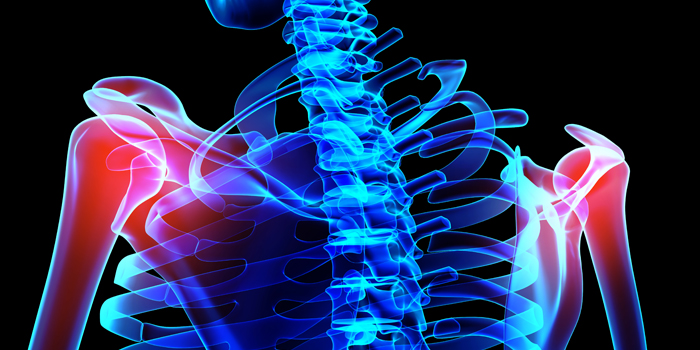

There are four joints that make up the shoulder: the acromion clavicular (AC) and sternoclavicular (SC) joint, glenohumeral joint (GH), and scapulathoracic (ST). The AC and SC joint hold the shoulder girdle together, whereas the GH joint is affected by soft tissue structures (the rotator cuff) and the ST joint is affected by the AC and SC joint and soft tissue structures, respectively.

GH Joint

- Held together by the rotator cuff and is extremely mobile

- Rotator Cuff: Supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis

- Other muscles that connect: both long and short head of the biceps, lats, pecs, and triceps

ST Joint

- AC and SC joint affect it because it’s not a true joint

- Promotes the articulation between the snap and back of the ribs

- Muscles that also affect the scapula: lats, levator scapulae, rhomboids major and minor, traps, pecs, and the serratus anterior

Below are four quick tests to determine shoulder function. They’re quick, simple, and to the point. I did not create these nor do I take credit for them.

The Bilateral Shoulder Elevation Test (BSET)

This is a simple range of motion test that can be done in ten seconds and will tell you which joints are responsible for the end range of motion in an overhead movement.

How to Perform

If possible, have the athlete remove their shirt to better observe their scapular motion. Have the athlete raise their arms straight over their head, thumbs pointed up and palms facing each other. As they hold this top position, take the time to walk around from the side and back, looking at their spine, ST, and GH joint orientation.

What This Tells You

Once the athlete raises their arms up, do you notice any scapular dysfunction? Compare bilaterally. Do both scapulas rotate upward and downward evenly? Do they excessively elevate or wing? Also, observe the scapula as they lower their arms. Does the inferior angle/border elevate, then depress? If there is no restriction and the athlete can go through a full range of motion, the upper trapezius could be dominant, taking over for the serratus anterior and lower trap. We always forget about the lower trap because it isn't physically shown in our tank tops, but the lower trap is essential for overhead shoulder function.

Watch from behind when the athlete attempts to raise their arms. Do their elbows flare to the outside of their wrists? If so, their arm is going into internal rotation, closing the sub-acromial space, which is where shoulder impingements come from. Usually, this comes from a lack of external rotation caused by the posterior rotator cuff, the lats, and even pec restriction.

Next Steps

If they cannot get their arms above their head without excessively arching their low back and have a curved thoracic spine, there could be either a mobility or a motor control dysfunction. At this point, perform the thoracic extension test. If there seems to be no spinal restriction then there is most likely weakness in the lower trap and the serratus anterior. Also, proprioceptive exercises such as movements that involve rotator cuff stability and trunk stability can be used.

WATCH: Dr. Ken Kinakin SPS Presentation — Subscapularis Strain and Testing

I like kettlebell arm bars here, or if advanced enough, the Turkish get-up. Also, movements that incorporate D1 and D2 shoulder patterns are great for regaining neuromuscular control of the shoulder girdle. D1 and D2 are short for diagonal extension/flexion patterns that replicate physical activity, used for a neurological connection between the brain and the pattern of the movement. Half-kneeling cable chops/lifts can be used to facilitate these.

Weakness in the serratus anterior is one of the biggest indicators of shoulder dysfunction. This prevents the scapula from staying against the thorax in rotation (this is the winging that you see). Any weighted protraction exercise is great here and can help strengthen that muscle and make the athlete become aware of where and how their shoulder is moving. These exercises can include protracting against bands, dumbbells, or kettlebells. These can be done supine, standing, or in other athletic positions.

Thoracic Extension Test

Since thoracic extension is very important in reducing shoulder impingement and helps in the upward rotation of the scapula about the thorax, it's crucial as strength coaches that we are aware of these mobility restrictions when programming overhead movements.

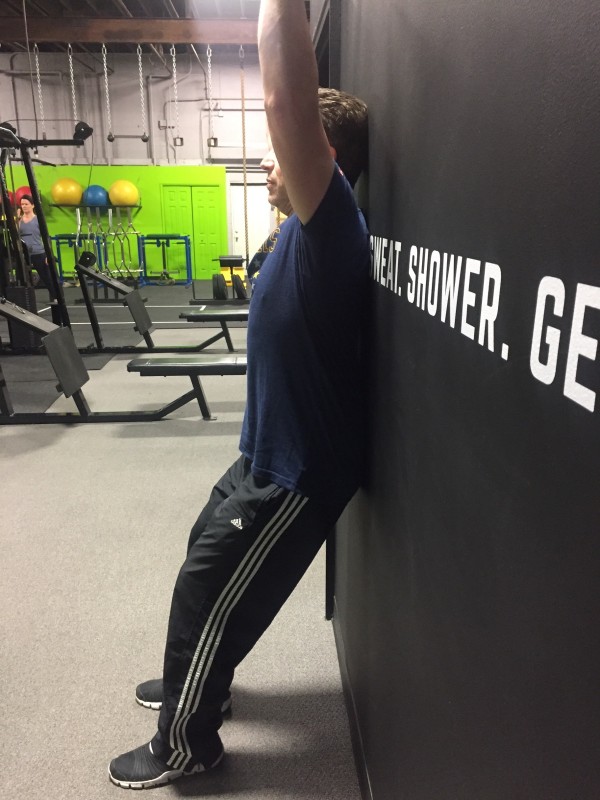

How to Perform

Have your athlete stand against a wall, knees bent slightly, and feet about a foot length away from the wall. The back of the head, upper back, and low back make contact with the wall. You want them to tuck their chin to try and flatten their spine, from neck to lower back, against the wall. They will raise their arms, thumbs up, palms facing one another, and attempt to touch the wall.

What This Tells You

If the athlete cannot flatten out their lower back against the wall and keep their chin tucked, there is a mobility restriction either originating from the T-Spine or the lats. If the athlete cannot go into a full range of motion while the elbows flare out to the sides of their wrists, there is some restriction in the glenohumeral joint. If the athlete can be cued to keep flat against the wall at all times and continue through the desired ROM, there is a neuromuscular deficit.

Next Steps

Have the athlete perform some T-Spine opening drills to help alleviate restriction. If after the exercise they are still not creating any movement from their T-Spine, perform the pec major muscle length test or lat muscle length test. If all mobility is fine, the athlete needs to be properly cued to flatten their spine and correct posture while going through the overhead range of motion.

Pec Major Muscle Length Test and Lat Length Test

How to Perform

Have the athlete supine on a table, keeping their lower back flat and head on the table. They are going to abduct their arm to around 150 degrees, or into a Y position. For the lat length test, the motion is the same as the thoracic extension test. However, the athlete is lying supine on a table, attempting to get their arms overhead.

What This Tells You

For both tests, if the athlete achieves the desired end ROM, there is a mobility restriction in either the lats or pecs.

Next Steps

Figure out which muscle is causing the ROM deficit (possibly both) and program some soft tissue and mobility work into the training session.

Conclusion

There are 12 muscles that act on the scapula. That is a lot of potential discomfort, dysfunction, and drama! As strength coaches, we need to keep our athletes healthy to ultimately get them stronger and move efficiently so they can better perform at their sport. With that being said, if any of the above screens cause pain, our responsibility is to refer them to other members of our sports performance team (physical therapists, doctors, athletic trainers, chiropractors, etc.).

Devee Sresthadatta, a physical therapist and owner of Hybrid Therapy states,

“False positives are always an issue with some tests of the shoulder due to how mobile the joint is. So a test may be positive for dysfunction but does not elicit a symptom, whereas another test is also positive and causes pain. If you can do a little mobility work and remove the pain and dysfunction of a test, great. If not, a referral to another professional is appropriate at that time.”

If the dysfunction becomes a chronic, recurring problem, then an assessment from a sports medicine professional is absolutely necessary.

As strength coaches, we must correct compensation patterns, get our athletes stronger and more durable, and prevent injury. The purpose of this article is to give strength coaches quick and easy tools to assess movements that may cause shoulder dysfunction, compensation, and pain in the future. This is a good way to prevent and overcome injury. As a strength coach yourself, you most likely compete in strength sports, or at least train like you do, so perform these screens on yourself and on your training partners and incorporate corrective exercises into your own programming as well.