Welcome to the final section of Back to Recovery Basics. In part one of this series, we focused on the foundations of recovery. This serves as an answer to the “why” question of recovery. It outlines the large role that recovery has in improving performance and maintaining your health and longevity in athletics. In part two we presented the big three, which must be the foundation of any successful recovery plan. If you are just joining the series, I highly recommend you take the time to read and understand these first two articles before moving forward.

Now that we have established why a solid recovery program is essential to your growth and what makes up the foundation of any recovery program, we can address how to supplement a recovery plan to specifically address your needs. By supplementing a recovery plan to fit an individual need, we are effectively personalizing that plan. However, I chose to use the word “supplement” rather than “personalize” in the title to reiterate the role of the content in this article. We have already built a large part of our recovery plan in part two by addressing sleep, nutrition and hydration (the big three). Therefore, the information contained in this article is to supplement and build upon our foundation of the big three. Just like pouring your time and money into whey protein and creatine won’t yield many results if all your diet consists of is frozen pizzas, putting all your effort into the supplemental side of recovery will not yield optimal results if you have not first nailed down the big three.

Part1: Back to Recovery Basics: Fundamentals of Recovery

This is also not to degrade the benefits of these supplementary recovery options. Let’s say the big three was 65% of the recovery equation and supplementary recovery methods made up the remaining 35%. It doesn’t mean the supplementary 35% holds no value. In performance, no one gives a shit about only realizing 65% of their potential. The goal is always optimal and many would probably rather not compete at all than to do it half-assed at 65%. The 35% is absolutely necessary, but you need to remember where the biggest piece of the pie is coming from. You cannot completely bomb a test worth 65% of your grade and then expect to rally on the remaining 35% and end up with a good grade. Rant over, we can move on now.

Identify Your Needs

Just as in any plan, success in a recovery plan will be dependent on properly identifying the areas that are in the most need of recovery. This could be as specific as a particular joint in the body (i.e. left shoulder) or as broad as your cardiovascular system hindering your recovery. In order to identify these needs in recovery, you must have an understanding of your sport, body, and state of training. In order to best manage the time available to devote to recovery, it is essential to devise supplemental recovery methods that best target each athlete’s personal needs. For now, the most important takeaway point for identifying your personal needs is that they allow you to have direction in your plan. Identifying the correct direction in your plan can be accomplished through understanding the needs of your sport, your body, and your current state of training.

1. Know Your Sport

What are the specific demands of your sport? What actions of your sport or activity cause the most stress and damage on the body? Which aspects of your sport lead to the most common injuries?

Simply put, different sports (and in some cases different positions within a sport) have different demands on the body. These varying demands cause a predisposition to specific injuries for each particular sport. Understanding and identifying these predispositions help define what areas are going to be stressed the most and require sufficient recovery in order to ensure peak performance and resistance to injury. To illustrate this, let's look at an overhead-throwing athlete, like a baseball player, compared to a basketball player. The consistent demands of throwing in baseball cause a large amount of stress on the shoulder. If this athlete’s shoulder’s stability or mobility is compromised as well, a percentage of forces created from each throw will be absorbed in the shoulder. Not only does this cause a decrease in performance, this athlete is also more susceptible to injury and a shorter career. In this sport-specific example, it is wise to consider the demands on the shoulder and implement active and passive recovery methods specific to the shoulder and the rest of the kinetic chain involved in throwing.

Photo credit: Ievgen Onyshchenko © 123RF.com

In the basketball athlete, the sport specific demands only mildly include the upper extremity and instead are more focused on the lower extremity. Forces on the foot, ankle, knee, etc., are accumulated due to the sheer volume of running, jumping, and cutting involved in a practice and game. Couple this with the very high frequency of games and it becomes apparent that to survive a long season, an athlete must be able to recover optimally. This athlete is much better off actively addressing their ankle stability to resist injury during multi-planar movements or utilizing passive modalities to allow the lower extremities to recovery between training and games.

2. Know Your Body

What is your injury history? Do you feel restriction of movement, weakness, or pain in a given range of motion? Do you wake up feeling refreshed and energized or are you constantly dragging ass all day long? Do you feel overly sore, weak, or tired from one training session to the next? Is your appetite up or down? Has your resting heart rate upon waking significantly increased (greater than five to 10 BPM)? Have you developed any compensation patterns in your movement? Can you achieve a proper range of motion in all joints? Some of these questions will point you to which area(s) need attention, some will identify whether your recovery is on target or if you need to increase or adapt it, and others will require the help of a professional.

Know your body is a multifaceted part of the planning process, as it requires both subjective and objective information. It is also arguably the most important factor in helping direct a recovery plan, as your body is actually telling you how you’re recovering. How you feel on a given day or week is subjective, as only you know how your body feels. Learning to identify what your body is trying to tell you can be very advantageous and can help identify when to mash the gas pedal or when to hold back. I tore my calf muscle three times in a four-year span because I was too stupid to listen to the same subjective information that my body gave me before it happened on each occurrence. Learning to understand the subjective information that your body gives you on a regular basis will allow you to achieve better auto-regulation, avoid injury, and know when to adapt recovery. Additionally, in order to recover and perform optimally, we must find out what is faulty and where there is opportunity to improve. The body will always be held back by its weakest or least capable link.

Subjective information allows you to understand basic knowledge of your body, but a full understanding of your body also requires an objective lens. It is essentially impossible to have a truly objective point of view on yourself. Many struggle to dial in their recovery and thus hinder their performance because they are unwilling to seek objective help. This is where the help of a fitness or health care professional can make a world of difference. These individuals should be utilized throughout the entirety of your life as an athlete or active individual to help maximize your recovery. We will discuss why along with how to seek out and identify these professionals later.

3. Know Your Training

What joints, regions, or systems, of the body are under the most stress? Are training stresses increasing or decreasing? Are these demands likely to increase or decrease in the short and long term (i.e. beginning a peaking phase for a meet, being four weeks deep into a 13-week season, pushing through the final few weeks in preparation for a fight, etc.)? Is training frequency (number of sessions in a week, month, etc.) changing?

There are many ways to monitor training loads on an athlete, and to investigate each of those methods to apply to recovery is simply over-reaching the intent of this series. For a basic understanding of how to determine recovery needs from training, we can simply look back to part one of this series to understand the interworking relationship between training and recovery.

Remember that training is the sledgehammer whose main purpose is to specifically target and create controlled destruction of the body. This causes the multitude of physiologic responses of recovery in the body, which increases performance and resistance to the stresses of the next training session. Because recovery for the purpose of increasing performance cannot occur without a training stimulus; it is dependent on training. Additionally, time spent training far outweighs the time spent competing, watching film, in meetings, etc. In powerlifting, for example, months of training are completed for the chance to step on the platform and (hopefully) attempt nine lifts. Therefore, if we are trying to establish and implement strategy for recovery, we damn well better understand the demands we are currently subject to in our training.

Training loads are always adapting and changing based on numerous factors. In almost every sport, these demands come in waves. To illustrate the need for variance in training, think about a scenario you have probably done dozens of times. Let’s say you just got into a hot tub. The water is not boiling hot, but hot enough that you have to take your time fully immerse. What changes in what you feel in the first minute compared to the 10th minute? Without going into the science of it, nothing happened to the water temperature; your body just adapted to the point that it got used to its environment, is comfortable, and is no longer strained to adapt to the heat. The water no longer feels “hot” to you like it did in that first minute. Suppose at minute 15 you exit the hot tub and immediately jump into a pool of “normal” temperature water. You will likely feel incredibly cold for the first few minutes until your body adapts and returns to normal. If you decide to re-enter the hot tub after five minutes of swimming in the pool, the water will again feel very hot and require adaptation from your body again.

In this scenario when we are acclimated to the hot tub, there are only two options to stimulate further adaptation in the body. We can either increase the water temperature or move to the pool to stimulate the body in a different way for a while and then return to the hot tub later. Sometimes increasing the water temperature is good enough, but we can only get the hot tub so hot before we seriously harm the body. The same concept goes for training. The body can only train the same way for so long before it is no longer stimulated to adapt and it can only train at full intensity for so long before it starts to fall apart.

The need for variation also applies to recovery. Most recovery tools and therapies are geared to influence or accelerate a physiological response. If we never change or wave our recovery stimulus, the body will similarly fail to adapt and respond. Changing recovery stimulus is option number two, and in most cases is a better option than mashing the gas pedal on training. The good news is that if you are able to get an expanded view of your training, you can usually tell when and how much (more or less) recovery you will need to plan on. When intensity and demand on your body are high, you should likely be pushing to recover. When you’re on vacation or have a planned deload after a meet, take a break and don't worry about pushing your recovery so much. We should always have a baseline amount of recovery, but do not need to always have it floored.

Part 2: Back to Recovery Basics: Fundamentals of Recovery

Finally, because some forms of recovery are forms of training, there is a possibility of an excessive amount of recovery being detrimental to performance. We must consider that sometimes there is a ceiling to how much benefit we can get from adding in more recovery. In those cases, the answer may be to remove some training stresses instead.

Select Your Recovery Methods

There are an abundance of methods, stretches, exercises, providers, etc., that can be used to recover. My intent is not to go over every single available option or to tell you my top five. Instead, the intent is to categorize and define the various types of supplemental recovery to allow you to investigate and utilize the ones that work best for you. Again, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, but rather a general template to supplemental recovery. To make things simple, these methods will be lumped into three categories: active recovery, passive recovery, and professional services. Many of these services and tools are easy to implement and widely available or accessible. Many are even available here at elitefts.com.

1. Active Recovery

Active recovery encompasses any method of recovery in which an individual has an active part in the recovery modality. This encompasses a wide range of commonly known methods such as stretching, mobility, therapeutic exercise, steady-state cardio, and self-myofascial release or instrument-assisted soft tissue manipulation (IASTM) using products like a foam roller or boomstick. It also includes other less commonly known methods such as self-stimulation like Reflexive Performance Reset (RPR) Wake-Up Drills. Active recovery is often the most useable and simple to apply as the athlete can often do them anywhere and are also often part of the start or end of a training session. For this reason, active recovery makes up the largest portion of supplemental recovery.

2. Passive Recovery

Passive recovery is a category of methods that does not require active participation from the individual receiving the treatment, nor do they require a professional to directly implement the therapy. This category includes many of the modalities that are known collectively as physiological therapeutics. These therapies mechanically perform a task on the body or target specific physiologic responses in the body to boost recovery. These modalities are very useful following a rigorous training session, injury, or during times of increased demand from training. In other words, this is a category you could base almost entirely off of your training intensity. If you are in-season or currently in an intense training block, increase passive recovery. If in the off-season, or coming off a competition, passive recovery can decrease.

A few examples of these are liniments, hot and cold therapy, contrast showers, Game Ready and NormaTec devices, ultrasound, cold laser, and e-stim. Passive therapies are very effective when timed well. The usage of this category will likely depend on the budget you have, as the equipment for most of those methods can be expensive. Having said that, options such as hot and cold therapy, contrast showers, and Epsom salt baths are very inexpensive and some facilities do exist with cost effective options to purchase access to other modalities that have higher equipment costs.

3. Professional Services

This category is reserved for utilizing the skills of professionals in the fitness and health care industry to provide an objective point of view in the recovery plan, as well as unique services that cannot be accomplished by the individual or athlete. This could mean hiring a nutrition coach, nutritionist, or doctor to monitor and direct your nutrition, utilizing the services of a conservative health care professional to keep your body moving effectively without compensations or restrictions or consulting a strength coach or health care professional to evaluate and critique your recovery plan.

Fitness professionals such as nutritional coaches and strength coaches can provide objective feedback in the world of function and nutrition that is specific to your sport. A nutritional coach can provide a plan that is completely detailed and personalized to you and your current state of function. This gives you the advantage of providing your body with the optimal amount and type of fuel it needs to perform at its best. A good strength coach can also provide many benefits when it comes to recovery. The simplest method is making sure your training program is tailored to you. Again, training has a huge impact on your ability to recover and many people have the idea that unless you are dragging yourself out of the gym or are sore for days, you have not accomplished anything in your training. This is incorrect and could be keeping you from recovering and increasing performance. Furthermore, a good strength coach can objectively identify weak points and susceptible areas in your body during training or performing specific movements that are causing excessive strain on the body and could predispose you to injury. They can also prescribe you correct methods for implementing active recovery in warm-ups, post-training, and on non-training days.

Health care professionals can also be utilized as your ace-in-the-hole to supplement your recovery. A good provider has a large amount of knowledge of the body and a multitude of tools at their disposal that are unique and only accessible through a health care professional. These tools include acupuncture, dry needling, ART, adjustments, manual manipulation, and hands-on evaluation of soft tissues and joints. Some who are reading this may be thinking, “I’ve tried physical therapy, athletic trainers, chiropractic, acupuncture, massage, etc., before and it didn't work for me.”

If that is the case, one or a combination of three things likely occurred. Either a) the health care provider was incapable of understanding your needs as an athlete or did not take the time to identify your needs; b) You didn’t follow their recommendations and only did what was convenient for you; or c) You utilized or they prescribed their care for pain management only and not wellness and performance (and even then, you likely waited until you were in the worse possible shape to seek out their help). Conservative health care providers can be absolutely essential to maintaining health and improving performance when they can sympathize and understand the needs of a given athlete’s sport and training and when they are utilized preventatively rather than after the wheels fall off. This is not to say that they cannot help you if you become injured or begin falling apart, but many injuries sustained in athletics are preventative in nature and could be prevented or minimized through consistent conservative care.

So how do you find the correct health care provider? My suggestion is to hold your health care provider to the same standards as you do a strength and conditioning coach to your training: What have their personal and professional experiences been in athletics? Who have they helped or treated? Who have they trained or under and where do they focus their continuing education on? If your health care professional’s values trend towards performance and athletics, you’re likely on the right path.

Some individuals may be more deterred from this category than the other two, as this category is typically the most expensive, but for those who are serious about improving themselves and becoming the best athlete they can be, here is a little secret: EVERY top level athlete has coaches and health care professionals that keep them performing at their best. Think of it this way: If you are the only one involved in your recovery and performance, you are only utilizing the knowledge and experiences of one person. When you hire professional help, you are gaining not only the knowledge of that individual but also the knowledge and the experiences of every other individual they have worked with to help formulate the best plan for you. Frankly, you get what you pay for, and utilizing a solid nutrition coach, strength coach, chiropractor, athletic trainer, etc., is essential for those who are invested in long-term success in health, fitness, or athletics.

Form Your Plan

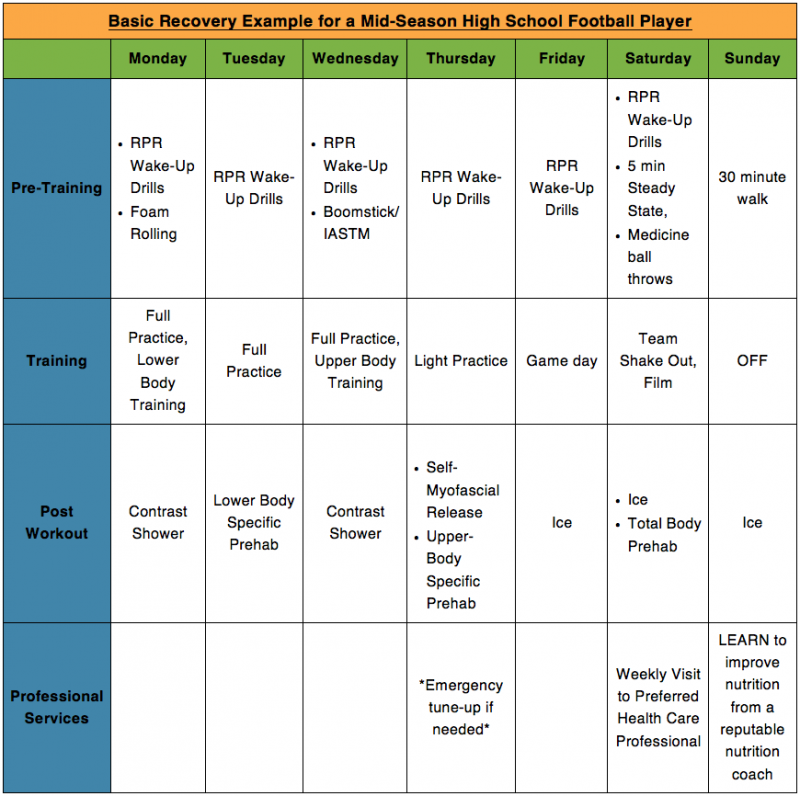

Now that we have identified individual needs, and defined the kinds of supplemental recovery available, how is a plan of action created to accomplish that? To formulate a plan, identify when opportunities exist for improving recovery in the micro or mesocycles of your training and then select a modality or method that aligns with your needs and the opportunity. This is essentially the blueprint of your recovery plan based on your training. For simplicity, these opportunities exist at three different times: pre-training, post-training, and non-training/reduced training days. For those who are more visually stimulated, I’ve included a basic outline for a possible recovery plan over a one-week microcycle.

Pre-training is essentially the warm-up prior to training. During this time, the concern is preparing the body to move. This is accomplished by stimulating proper neural output and muscle contraction through normal ranges of motion, kick starting the cardiovascular system, and raising the core temperature. This can be accomplished through RPR Wake-Up Drills, light steady state cardio, dynamic mobility drills, band-resisted movements to engage postural muscles, and even quick explosive movements such as plyometrics. The exercise selection should be simple and specific to the movements required by upcoming training session and are geared more towards resisting injury and preparedness to accomplish work. This should be relatively short and to the point.

The post-training window is the perfect time to focus on restoration. The big three are incredibly important for reasons previously discussed, as are simple passive recovery methods such as contrast showers, cold therapy, and Epsom salt baths. This is also a time when seeking professional services from chiropractors, athletic trainers, and physical therapists can be effective as well. In the collegiate and professional athletics setting, getting therapy multiple times a day specifically following training is incredibly common. After training, these services are not only therapeutic for the aches, pains, and possible musculoskeletal imbalances sustained in training, but can also help quicken recovery.

For example, an athlete that has just deadlifted will have a distinct amount of tension in the hamstrings, glutes, and low back that could result in reduced recovery or restriction of the joints of the spine and lower extremity. By utilizing myofascial release techniques and adjusting post training, there is a reduction of tension in the muscles similar to as if they were injured or hypertonic. Proper joint motion is also ensured. The theme for post-training is rest, refuel, and restore to normal as quickly as possible.

Non-training or reduced training days can vary depending on the training regimen. For strength athletes, this may be a cardio day or a completely off day in which they can focus purely on recovery from the previous day’s training. An athlete that is training six days a week and is in-season may still have a decent workload such as full practice, but no lifting. Either way, this is where the most opportunity exists to devote time to recovery. All three categories of supplemental recovery are fair game here. The focus should be on recovering from the last training session, active recovery targeted to bring up weak points, correct musculoskeletal imbalances, improving deficits in joint range of motion, and reducing or addressing injury.

For example, a quarterback is looking to recover from the previous training session, which was lower-body dominant, and his athlete’s athletic trainer has also identified the need for additional work on his right shoulder, as he has an imbalance between his scapular stabilizers and prime movers. This athlete may choose to use a passive modality like NormaTec on his legs to mechanically stimulate fluid drainage while heating his shoulder for the banded pull-parts, scapular retractions, and shoulder mobility he has been prescribed as prehabilitation. He then may decide to do some basic hip and lower body mobility, abdominal strengthening exercises, and then head to film with a couple bags of ice. This is simple and direct but ensures the athlete is ready to go for practice this afternoon.

As another example, a strongman athlete who just finished a brutal event day yesterday and is three weeks away from a big competition has decided to throw the kitchen sink at recovering his body on a non-training day. He starts with RPR Wake-Up Drills and some instrument-assisted soft tissue manipulation with a boomstick and then moves right into active recovery with light sled pulls as steady state cardio. Afterwards, he hits his weekly planned sets of reverse hypers and banded rounded back good mornings, as his sport demands as strong a back as possible. Then he downs one of the seven meals planned by his nutrition coach, heads off to an appointment with his massage therapist, and then his chiropractor. He may also utilize a few passive modalities available at the chiropractic office and then go home and just finish the last drops of his two gallons of water before doing a contrast shower and going to bed early to get some additional rest. This athlete needs to drop 12 pounds to make weight in three weeks, so there is no partying with friends, eating junk, or staying up late. This example should reiterate that if you want to perform at your best, recovering must be a priority and sometimes, your “off-days” are just as time-consuming as training days.

I hope you enjoyed this three-part series and were able to come away with a better appreciation for recovery’s role in your performance, health, and longevity. My goals in this series were to establish a basic understanding for young, beginner, and intermediate athletes to help them implement and prioritize recovery in their training and athletic careers. Too often, athletes do not learn the importance of recovery until they are sidelined or their career is threatened by injury. It is my goal as a professional and fellow athlete to facilitate, educate, and support athletes to help them enjoy the activities they are passionate about with increased longevity and realize their true performance potential. If any of the concepts in this series need reinforcement or further detail, please do not hesitate to reach out to me.

Header image courtesy of Kheng Ho Toh © 123RF.com

Dr. Tyrel Detweiler provides care for athletes across all sports with a majority of his experience coming from working with athletes in collegiate and strength sports. He holds a doctorate in Chiropractic and a Master’s of Science in Sports Rehabilitation. He is the owner of Mid-South Spine and Sports Performance in Cordova, TN. This facility has a unique relationship with NBS Fitness, giving him access to some of the best strength athletes in the Mid-South. He was a former member of Mizzou’s Sports Medicine Team and is currently in his second year as the chiropractic physician for the University of Memphis Athletics. Tyrel was a college football player at the University of Iowa and has competed in powerlifting and strongman since 2010. He is also the current Mississippi state representative for United States Strongman. He can be reached at drdetweiler@midsouthssp.net.