Introduction

Now that the hockey seasons are coming to an end and athletes will begin training in a few weeks, I felt it would be the right time to lay out what I deem to be the most important exercises for off-season training of hockey players. I want to preface this article by saying this is MY opinion based on MY experiences. There are tons of different exercises, and each should be individually selected based on the athlete’s needs and capacities. In fact, my article is contradictory because no single exercise is good for every athlete. Considering this, the purpose of this article is to provide exercises that will target 80 percent of the hockey population based on the tissues they target, biomechanical similarities to the sport of hockey, and safety of execution.

Lower Body

Main Movement: Front Squat or Safety Bar Squat

In my opinion, the front squat and the safety bar squats are the best squat variations for hockey players. Why? Mainly because of its beneficial effects on the strength of the spinal erectors and its similarity to the posture maintained while skating. One of the major weaknesses of hockey players is their back. If you watch a hockey player during the course of a 45-second shift, you will realize it’s not the legs that are the limiting factor. It’s actually the lower back and erectors. Being a former player myself, you are essentially isometrically holding an arched back good morning in the bottom position. After 45 seconds, your back is surely going to give out. Performing heavy front squats or safety bar squats will strengthen the erectors and increase lower body hypertrophy and strength in a more hockey-specific posture.

WATCH: Must-Have Equipment for Any High School Weight Room

In terms of programming, in general, I prefer using the safety bar squat only for anything over six repetitions a set and either variation for sets below six reps because it’s hard to stay in a front squat for that long without passing out or having the bar slip.

Secondary Movement: Poliquin Split Squat

I don’t know if this is the correct name for these split squats, but I got these from the great Charles Poliquin and they have always been regarded as the standard split squat for me.

Slightly different than a regular split squat, the legs are slightly farther apart from one another. The toes of the front foot are pointed approximately five degrees externally. The chest remains upright, and the movement begins by pushing the knee as far forward towards your toes while keeping the back leg and knee as straight as possible. Obviously, the back knee will bend slightly, but by minimizing the bend, the athlete will get more hip extension and get into a deeper squat with the front leg.

This might be one of the most beneficial exercises for hockey players for a couple of reasons. First, it is a great tool for assessing the athlete’s movement capacity and increasing their mobility. The exercise requires a great deal of ankle dorsiflexion and hip extension, which many hockey players lack because of the biomechanics of the sport. Hockey involves wearing a boot with a steel blade. Nowadays, these boots are extremely stiff. Therefore ankle movement is minimal. Hockey also requires spending a lot of time in hip flexion. Yes, taking a stride requires hip extension, but it doesn’t necessarily mean the athlete can fully extend their hip. Increasing ankle dorsiflexion can help improve ankle and knee health while improving hip extension can alleviate potential lower back pain and increase the athlete’s ability to extend their hips while skating and thus increase their stride length.

When observing your athlete perform the exercise, look specifically at the front heel and the back knee. In general, lack of ankle dorsiflexion will cause the athlete to raise their heel to achieve more depth in the squat, and large bending of the back knee will compensate for lack of hip extension. By looking for these breakdowns, you will be better able to determine the athlete’s needs and possible progressions or regressions.

I love the split squat because it also targets the vastus medialis and the quadriceps and adductors. Strengthening of these muscles contributes to improved knee and hip health. One of the most common injuries or strains hockey players experience is in the groin and adductors. It can either be because the muscle is too weak or too tight. This split squat allows the adductor to be strengthened in a lengthened state, therefore, increasing the muscle's ACTIVE range of motion and preventing injury by improving the tissue’s load-bearing capacity throughout a larger range. Basically, contracting and strengthening the tissues in a newly acquired range allows for the tissue to be resilient at that length; therefore, the next time the athlete’s tissue is put into that position, the risk of injury is diminished.

When programming the Poliquin split squat, there is a lot of freedom in terms of intensity and volume. The exercise can be used as a primary movement or a secondary movement, depending on the goal of the exercise and the phase of the off-season. With my beginners, it is a staple throughout their entire off-season because it provides them with a foundational base of mobility, strength, and hypertrophy. For more advanced athletes, the split squats are emphasized more in the early part of an off-season as part of the structural balance phase and may only be included later if needed.

Based on experience, here is the typical progression I use based on the mobility and balance of the athlete:

- Front Foot Elevated – Medium Block

- Front Foot Elevated – Small Block

- Normal Poliquin Split Squat on the Floor

- Rear Foot Elevated – Small Block

Accessory Exercises: Leg Curl, Back Hyperextension, or Reverse Hyperextension

As you can tell by the exercises listed, the posterior chain is the primary emphasis for the accessory work. Why? Firstly, hockey players are normally very weak in the posterior chain (quad dominant) from skating with a slight heel elevation. It is well known that an imbalance between quadricep and hamstring strength increases the risk of knee injuries, so posterior chain work will mitigate the possibility of injury. Secondly, the posterior chain, primarily the hips and glutes, contributes to skating power and speed. As I mentioned earlier, skating involves a great degree of hip extension. What extends the hips? BINGO! The hips, glutes, and hamstrings.

Now, I listed three exercises because they each target the posterior chain slightly different from one another. In a simplistic manner, here is how I view each exercise:

- Leg Curl: Hamstring KNEE flexion

- Back Hyperextension: Hamstring and Glute HIP extension

- Reverse Hyperextension: Glute and Lower Back HIP extension

Although I only listed those three, each exercise has many variations, again depending on the needs of the athlete and the phase of training:

| Leg Curl | Back Hyperextension | Reverse Hyperextension |

| Lying Leg Curl Seated Leg Curl Standing Leg Curl Toes In (Adductor and Semimembranosus) Toes Neutral (Semitendinosus) Toes Out (Bicep Femoris) Plantar Flexed Dorsiflexed Poliquin (Dorsiflexed concentric, Plantarflexed eccentric) | 45 Degree 90 Degree (aka GHR) Weighted: Dumbbells Med Balls Barbell on Shoulders Barbell on Floor Toes In Toes Neutral Toes Out | Toes In Toes Neutral Toes Out Single Leg Double Leg |

There are obviously more variations possible, but you get the point. If you implement one of the exercises on one lower body day and a different one on the other lower body day, you will be golden!

Upper Body

Main Exercise: Incline Press

The main reason I prefer the incline press over other presses (if I could only choose one) is to protect the shoulder joint of the athlete. In my experience, very few hockey players have the active ability to reach full shoulder extension. I mean bringing their arm straight up and having their bicep in line with their ear without contorting the rest of their body or compensating with another joint. What happens if I tell them to press over their head? Either they hyperextend their lower back to get the bar up, or they push the bar slightly in front of them instead of straight up.

Now, I am not saying I am against vertical pushing! I would absolutely love to program them for all my athletes, but I am not always comfortable from what I see. Instead, I just put them at the steepest incline that suits their current active range of motion. If I have extra time with the athlete, I will include some shoulder mobility work in his program. If he reaches a proficient level of mobility, then I feel comfortable doing overhead work.

I also prefer incline pressing over flat pressing for protecting the shoulder joint. Most hockey players do not know how to bench properly. Yes, you can teach them how to set up properly, and it is important, but the bench press is not their sport, so it does no good wasting extra time teaching and practicing technique. Doing close grip benching might not necessarily work either. If you look at most hockey players doing close grip work, their elbows drop below the bench, causing the shoulders to roll forward and place more strain on the shoulders and pecs.

At the end of the day, a press is a press. Yes, the angles, grips, and setups change the emphasis of the exercise. Still, in my opinion, the incline press can kill more birds with one stone than the other pressing variations while being safer and easier to perform.

Supplemental Exercise: Pull- or Chin-up

I know I just mentioned doing overhead work is not great (in my opinion) if the athlete lacks a proper active range of motion, so why would I include overhead pulling? First, it’s a closed chain exercise so the athlete can adjust their body accordingly if there is a lack of mobility, without detriment to the rest of the body. Second, hockey requires a great deal of grip and bicep strength. Shooting and stickhandling can be greatly improved by an increase in grip strength.

Additionally, grip and bicep development help protect the elbow joint. Finally, and most importantly, vertical pulling is very beneficial for shoulder health and strength. Not only do chin-ups and pull-ups strengthen the lats and back, but the rotator cuff and scapula as well, both of which contribute to improving posture and shoulder health. They are also a great way to increase active mobility in the shoulder joint. By actively contracting throughout newly acquired ranges of motion from the stretch, the athlete strengthens the tissue at that position and increases its capacity to sustain forces. Again, if the athlete is forced into a range that he previously could not access and there was no strengthening of that range, the likelihood of injury is much greater.

Accessory Exercise: Rows and External Rotators

The accessories for the upper body are very basic. The sole purpose of them is to build shoulder resilience. I heard this term from a consultation with hockey strength coach Ben Prentiss, and I loved it. Due to the tremendous amount of forces the shoulders experience during a season, from shooting pucks, body checking an opponent, and absorbing body checks for 82 games a year, the shoulders NEED to be extremely resilient. By far, the most common injuries in hockey occur in the shoulders. The accessory work at the end of the sessions focuses on adding more upper body pulling volume, primarily in the upper back, and strengthening the external rotators of the shoulder. Both of these will help the athlete tremendously in preserving their shoulder health during the course of the grueling season.

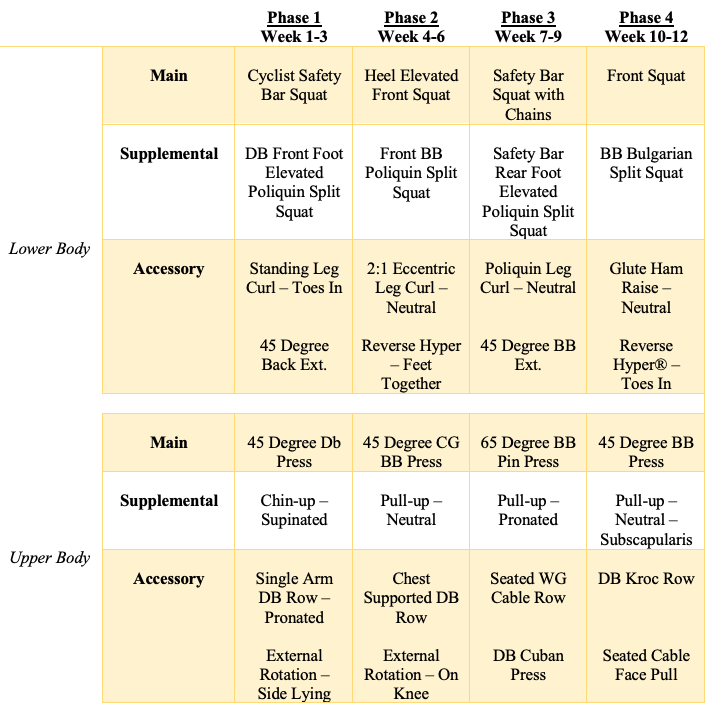

Progression Example:

Conclusion

I am sure some of you will disagree with my selections, and I would love to hear your reasoning. My goal is to provide exercises that target numerous weaknesses of the athlete at once. The main movement focuses on strength and hypertrophy. The secondary movement is used for joint health and hypertrophy. The accessory finishes up the session by strengthening the areas prone to injury. The sessions do not have to end there. You can add jumps, med ball work, prehab exercises, whatever. This is just what I deem the bare bones and essentials for off-season hockey training.

Max Daigle is currently finishing his undergrad at McGill University in BSc. Physiology, with a Minor in Kinesiology. He played NCAA Division 1 hockey at the University of Vermont before transferring to McGill, where he played two seasons. Max is the assistant strength coach at Axxeleration Performance Center, under the mentorship of Mark Lambert (Head Strength Coach Tampa Bay Lightning NHL) and Sebastien Lagrange. Axxeleration Performance Center is a private gym just outside Montreal, Quebec, that works primarily with hockey players.