I’ve had a lot of questions lately come up regarding the importance of corrective exercises, and moreover, when to do them on one side of the body or both when addressing asymmetries. Actually, the idea of asymmetrical movement patterns tends to be a hot topic amongst athletes today and is a special interest of mine. Take a look at my previous article regarding asymmetries and you’ll see why. It seems there’s some general confusion within the community about how to address these, and it almost creates some uncertainty-based fear. It’s a process I’m still working through myself. Through trial and error, I’m basing my own treatment on a few principles. These asymmetrical movement patterns are important to address from two perspectives:

- Forward thinking: injury prevention. It makes sense to think that increased load transmitted through one portion of the body will eventually lead to susceptibility to breakdown.

- Retrospective thinking: “injury treatment.” Is this pattern a result of something else going on in the body? Are asymmetries indicative of injury?

There are a few key concepts necessary to understanding some of the framework that lends itself to discussing these ideas. I want to preface this by saying this is a very, very broad overview, and by no means comprehensive; each of these concepts could become a very long article on their own. Moreover, in some ways, our asymmetries may not be a bad thing. I’ve met linebackers and elite level powerlifters who are so strong in their particular patterns of dominance that it is actually a huge factor in what makes them so good provided they can alternate out of that dominance when appropriate. My intention with this article is not to tell you how to rehab or prevent injuries, but to give you foundations from which you can continue to build your knowledge. Take ownership of that.

In some ways, this may be overthinking for a lot of athletes, but I’m a believer that the more educated we are, the less “fear” injury will put into us. As an athlete, it bothers me to see friends and fellow competitors following any hot trend in “rehab” because it seems like a good idea rather than understanding why it may or may not be.

This is a longer article, because I feel the information is important. I will split it into two parts to make it easier to digest understand. We owe it to ourselves as athletes to understand how and why our body works the way it does. Skip to the “review of takeaways” at the end if you are short on time, but I highly encourage you to return and read the rest of the content. It’s a bit dense, but worth understanding.

The Concepts

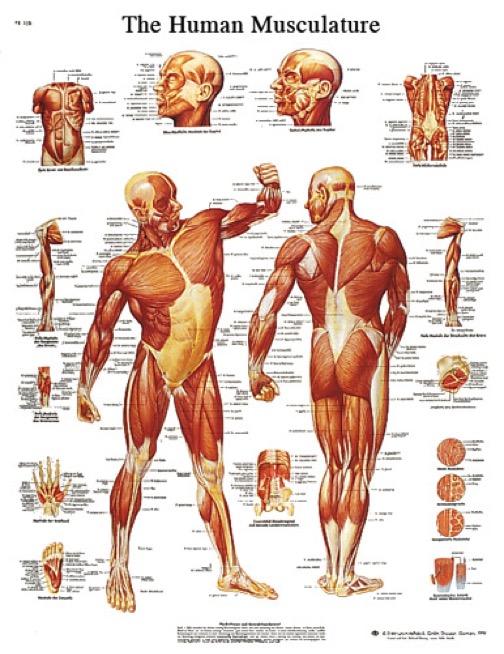

Tri Planar Motion: Many muscles work in more than just one plane or direction. Go to google right now and look up an image of “anatomy chart.” Look at lines of attachment — not in the quick glance that you may usually give, but really look at the muscle fibers involved and appreciate the fact that very rarely does a muscle work in only one straight simple line of pull. There’s generally some angulation to muscle fibers. Appreciate that.

Although a bit cartoonish, I appreciate that if you look closely at this photo, you’ll notice that certain muscles have fibers that don’t all run exactly the same, and that with movement, changes in position inherently differentiate left and right sides. Take a look at the lats and traps in this photo. I strongly encourage you to do a search on your own and really look at things. Good starting points: Psoas major, the adductor group, glut med and min, and the hamstrings.

Our bodies move around three general directions: front to back, left to right, and around a rotational axis. Very rarely does a muscle work exclusively in one plane. Even the bicep, which we think of basically as an elbow flexor, also acts to supinate or rotate the forearm, it’s no longer a “one movement muscle." You can’t tell me that as you’re benching, trying to grip the bar well with an emphasis on squeezing or breaking the bar, there isn’t an element of rotation or torquing applied.

We like to put muscles into a box based on what primary action they do. Most of the time, that’s a safe road to take without majoring in the minors, such as individual differences in attachments, positional changes, and a muscle’s relative strength at a certain point in the range. As we move and the muscular attachments move, the line of pull may alter the motion the muscle acts in or even how strong it is in that position.

MORE: 4 Things Your Body Needs to Stay Symmetrical

That got really confusing, really quickly. Let’s clarify. We often talk about our gluteus medius as a major player in helping us keep our knees “out” during a squat, and indeed, the glut med is a primary abductor and contributes to external rotation — the “knees out” motion. There are some schools of thought that advocate the anterior fibers of the gluteus medius as an internal rotator (e.g. the opposite of how we usually think of it) when the hip is in higher degrees of flexion, or when the “socket” of the ball and socket hip joint is in a particular position. This same school might say that the posterior fibers favor abduction and external rotation as we move out of flexion. Whether it is an “active” internal rotator or more acts as a femoral head stabilizer in that position, people from different schools of thought will debate. I’m not interested in debate right now, my point is this: a muscle’s role may change based on joint position. And it can be incredibly complex. So what do we, as athletes, do with that?

We like to think “big picture” about how our bodies move. And given the degree of variation and amount of change the small scale things actually make, most times our big picture thinking is more than sufficient. When all’s well, keep it simple, and don’t major in the minors.

When it isn’t enough is when we neglect the details that may clue us in on one of the two points mentioned at the very beginning of this article: injury prevention or injury indication.

Takeaway Point 1

Our muscles need to be strong and stable in more than one direction of motion, and throughout an entire range of motion. Continue to strengthen muscles in whatever weak points may be evident — internal or external rotator. At the end of it, you need to be strong throughout the range. Things will come together. Weak at the bottom of your squat? Strengthen that point, in similar positions, for maximal carryover, while continuing to maintain the remainder of the range.

Neuromuscular Activation and Patterning: As mentioned in a previous article, I have an unending amount of information to learn regarding motor control and patterning. However, I do know that in general, we like to think about muscles as “on” or “off,” like a light switch, and that the pec working to press is the on/off, neglecting the role of stabilizers and opposite muscle groups. Additionally, there are a number of schools of thought that propose that muscles work together in chains, and that every chain has an opposite chain. This has greater applicability to compound movements.

It’s the same concept as “pushing” versus “pulling.” We internally know that there’s an opposite group of muscles that opposes the action we’re completing; control of those opposing forces is a large part of what gives us stability as athletes.

My clinical mentor describes muscle activation as follows: rather than an on/off switch for a light for a muscle, imagine a dimmer switch. Chains of muscles need to have a sensitive dimmer switch that promotes finding an appropriate balance between opposing chains. If you bench without any control through your posterior chain, you lose some of your pressing strength. This is a component of technique: balance of these chains. Essentially, these “dimmer switches” for opposing muscles need to be balanced in a way that permits maximal force generation coupled with maximal stability. Rather than thinking of these chains in opposition, picture them as a balanced couplet to permit a full range of stability, mobility, and strength.

Many times, injury or dysfunctional movement occurs when the dimmer switch for one chain, or even singular muscle, grossly overpowers the other. These chains are largely controlled by the nervous system. Remember this.

Takeaway Point 2

Our bodies build patterns and habits based on muscles or chains of muscles we routinely “access.” We need to practice balancing the dimmer switches on these chains for healthy movement. That may look different between athletes, meaning whether you are looking at injury from a retrospective or proactive standpoint, your “rehab” may look different from your training partners.

Chris Duffin writes about the importance in corrective exercises here. I am beyond excited to see good content with regards to injury prevention, addressing a problem before it really becomes a problem, and encouraging lifters to be a bit less fearful. He summarizes ideas far more effectively and succinctly than I could:

“I do not suggest old school push through the pain. This approach is a downward spiral. Just as with the off-road analogy, mitigate the damage first and then move to fixing the problem:

-

Modify movement to prevent worsening.

-

Push limits of movement but not into pain.

-

Increase movement in progressive manner but not into pain.

-

Being progressively loading movement but not into pain.

-

Quality of movement must be of critical importance in every step.”

Reread that last point: quality of movement. If you’re dealing with asymmetries, you’re probably seeing or sensing it in the quality. It is possible that dissecting the quality may give you the answer you’re looking for: the why. It does require a decent eye, and a willingness to step back objectively, and likely checking both your strength and intellectual ego at the door. It can be very difficult to see or feel these things yourself unless you have a very high level of kinesthetic awareness. Video has been incredibly helpful for my own rehabilitation in that it’s permitted me to see what’s happening in my whole body rather than just the isolated joint or structure where pain manifests. The pain can be a result of dysfunction at one or multiple other sites. Be on the lookout for an article regarding how to address this in the future.

Takeaway Point 3

When thinking about the type of rehabilitative or corrective exercises, the answer is generally it depends, because the purpose of the exercises is to address the why while continuing to manage symptoms. Without addressing the why you’re going to be chasing your tail.

Let's return to the perspectives from the beginning of the article:

- Forward thinking: injury prevention. It makes sense to think that increased load transmitted through one portion of the body will eventually lead to susceptibility to breakdown.

- Retrospective thinking: “injury treatment.” Is this pattern a result of something else going on in the body? Are asymmetries indicative of injury?

With regards to practical application, a good place to start is to ask those you trust to help identify these patterns. You need to then examine the when and the why, because that will drive how you address them. There are a number of factors that can lead to dysfunction: joint mobility, muscle extensibility, muscle dysfunction, or even “integration” of these patterns. If the problem is not unilateral strength, doing more and more unilateral exercises isn’t going to address the problem; you’ve missed the why. Here’s a decent starting point:

What does the motion look like on one side versus the other? Where do you feel muscle work as you complete the exercise? What is occurring at the joints above and below the site of pain or asymmetry? Does it occur during unilateral movements, or is it more an integration issue when both sides are under load? What if you remove the load? Is there pain or weakness at one particular point in the range of motion? Take that a step further—if you have someone move a limb for you, completely passive, does it change anything? Does the pain or dysfunction occur with changes in the speed of motion? Bear in mind this may be something as simple as “one side is just weak or underdeveloped.” Often times in what we do with powerlifting, addressing that alone can help fix things.

There are a million directions to go with these questions, but ultimately, all they are designed to do essentially is get you to the root of why by asking one more question. While there are a myriad of reasons, there are a few key suspects that I tend to run into when working with athletes, especially being overdeveloped in one muscle group or chain of muscles. This imbalance can actually make it harder to even find the opposite group.

My clinical mentor has also helped me learn that in a lot of ways, certain asymmetries or imbalances aren’t necessarily a bad thing. I’ve seen elite level athletes that routinely accessed the pattern they’re strongest in, and strengthened it to a point that’s given them an increase in sport performance.

RELATED: My First Trip to elitefts and Talking with Dave Tate

Example of an advantageous imbalance or asymmetry: A lineman can come off the line and hold their opponent, which is advantageous, but outside of a particular task, that advantage is lost. Their imbalance is advantageous for sport performance, in their particular movement pattern. This is not entirely related to powerlifting, but a good visual for the topic.

When asymmetries can become problematic is when an athlete cannot alternate out of the strong pattern to the opposite when strength isn’t necessary. Can the above lineman even isolate his glute, or is it so “turned down" that he recruits every muscle in his leg when he tries to isolate it? In time, this can cause breakdown. Let’s come back to the dimmer switch theory. I highly doubt that a person with a 500 or 600-pound squat has a weak glute. There is, however, a good chance that their glute is dysfunctional and has been patterned to have its dimmer switch turned down below a certain threshold.

Why?

This is where you can start to integrate some of the previously mentioned questions. They are likely going to lead you to the direction of rehabilitative work to get out of an asymmetry that may exist. Ideally, you want to pattern your body to re-learn or re-pattern by addressing the why. This may look different for each athlete depending on the root of the problem.

For one athlete, this may mean using primarily unilateral loading to encourage proper activation of a muscle in a certain position, as discussed earlier. For another athlete, for a benefit threshold to be reached, it may mean integrating one side of the body to more effectively work with the other; that muscle may be strong enough to work unilaterally, but not patterned to integrate with the other side in a bilateral compound lift. The trick with all of these is to make sure you’re getting what you need to out of these; once you find the why or when, it’s simpler to fix.

I’ll return to the example given in the first takeaway: your left side feels weak out of the bottom of your squat? How does it feel compared to the right side in unilateral work, in the comparable range of motion? How does it look? If it’s different, you’ve got your answer. If it’s the same strength wise, but your body does something silly as soon as the bar is on your back, look above and below the hip for the why. Dissect it. You do have the ability to do this. It’s not as complicated as we have to make it, so long as you learn to think without overthinking.

Guys, hear this. You’re a smart group in so many ways. Your approach to rehab or maintaining health should be no different than you are with your training: have a reason and rationale for why you do something, and make sure you’re getting it!

A Quick Review:

- Muscles or chains need to be strong and stable in more than one direction of motion, and throughout an entire range of motion. The role and ability to generate force of these muscles will change at different points in a movement. Don’t let that scare you, and don’t overthink it: keep it simple and pursue strength, mobility, and stability throughout a full range of motion.

- Our bodies build patterns and habits based on muscles or chains of muscles we routinely access. We need to practice balancing the dimmer switches on these chains for healthy movement. That may look different between athletes, but in general, it is healthy to be able to access one pattern as well as its reciprocal or alternate. The good news? Our bodies like patterns! Build a solid foundation for movement, maintain it, and your body will thank you for it.

- When thinking about unilateral versus bilateral corrective exercises, the answer is generally it depends, because the purpose of the exercises is to address the why. A good way to assess this is by video footage, photo, or even range of motion. Look at range of motion before onset of pain or dysfunction, or amount of weight lifted before onset. Either way, you need something you can assess, treat, and re-assess. This tells you if you’re actually creating change.

Again, at the end of the day, it really doesn’t need to be that complicated. Alexander Cortes has been a huge voice of simplicity for my own rehab. If the issue is related to strength or underdevelopment, do an extra set of whatever you may need to on the “weak” side. Just make sure you’re getting what you need to out of your rehab. My left glute is perpetually lagging, so I do an extra set of single leg work on my left side. If you’re trying to strengthen your glute and you’re consistently feeling quad, change something so you DO feel glute. Be intentional, just like you are with your training.

Regardless of the why I highly encourage unilateral work as preventative, but it is important to be aware of the quality of movement. Start working to alternate out of whatever pattern you typically access during your training. Remember, be maximally strong where you need it, when you need it. The ability to turn that off or dial down the dimmer switch when its appropriate can mean increased effect when you do get into the extreme positions we do. Think about it this way: you don’t walk around all day with your muscles engaged like a heavy squat, maximally extended and elbows tucked under the bar. If you did, it’d be hard to really exaggerate or find that in training. A good starting point might be figuring out how to dim down the switch for that pattern during the day, permitting increased access when you do have a bar on your back. Part of your strength comes from being technically sound in turning up the dimmer switch when necessary. Think long term, assess quality of movement, and encourage patterns that promote longevity and a long lifting career rather than quick gains from dysfunctional movement.

5 Comments