Jumping into the subject of exercise selection and creating hard and fast rules is not usually my style. I am a firm believer in the all too common "it depends" when answering, "When should I do certain exercises?" For athletes and coaches, the answer to this question will depend on who the person is, their goals, training age, injury history, level of skill, etc.

That being said, I have been getting a lot of questions via social media and our Youtube channel about how to set up training days in regards to "X" goal. So, instead of creating these hard and fast rules, I want to share some information and principles to consider when building out your training day/week/block/whatever. You'll better understand what forces are at play during a training session so that you can ask better questions of your coach or yourself, and therefore make better choices about how you should complete your training.

RELATED: The elitefts Scholastic Back Raise: 8 Exercises You Aren't Doing

You are right; I am NOT just GIVING you an answer because I don't know a single thing about you. My role here is to give you some information so that you can be a better version of yourself and elevate your programming and exercise selection abilities which lead to you ultimately growing as an athlete, lifter, or coach.

Internal Vs. External Stability

You've heard me repeat the word "stability" over and over in video demos and podcasts.

"Internal Hip/Shoulder Stability"

"This externally stabilized exercise…"

Blah, blah, blah.

Now, when I say "stability," I'm referring to the ability to resist against forces.

Pretty simple, right?

When I talk about stability, I am not just talking about standing on one leg, on a Bosu, being thrown flaming medicine balls. What I'm referring to, in this regard, is our ability to maintain quality positions and postures as forces try to enact their way on us.

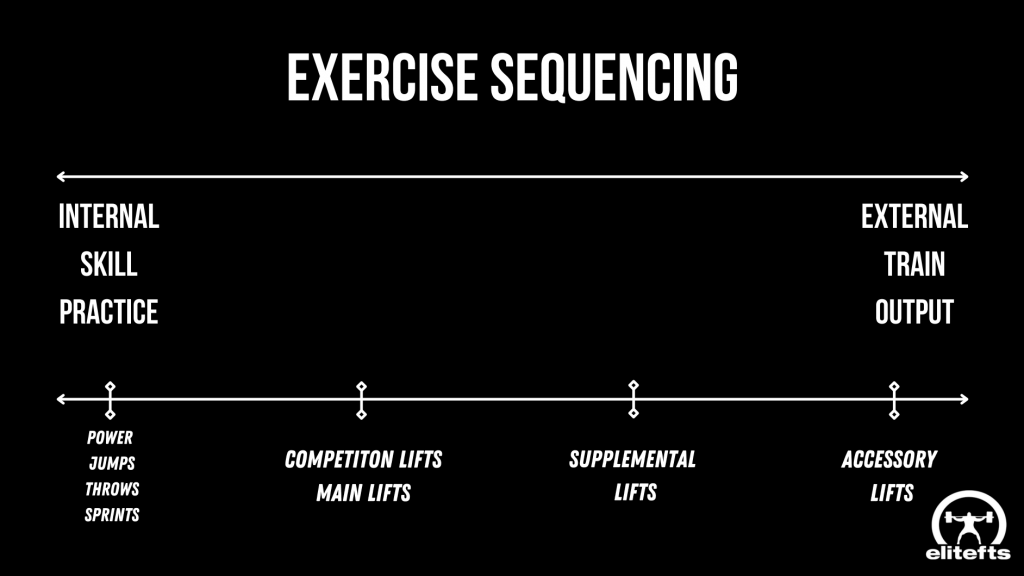

To take this conversation to the next level and better understand how we utilize stability in our training, we need to break stability into two categories: Internal and External.

Internal Stability

Internal stability is your body's ability to resist force through braces, skill, and the ability to maintain positioning without the aid of external forces. In layman's terms, it is how you can stabilize your body without holding onto something or having an outside force/machine/object assisting you. When thinking of internal stability, think of what you have to do to complete a back squat. You need to root your feet, brace and stabilize your torso, and remain in that position as you descend in the hole. The limiting factor is your ability to maintain that position and posture.

External Stability

External Stability is when we are relying on factors outside of our body to help keep us in a position or posture. Instead of thinking about a back squat here, think about a leg press. In the leg press, you are externally stabilized by the machine, which puts you in the position necessary to complete the exercise. Internal bracing is far less important, and you are able to push closer to true muscular failure as opposed to technical failure.

Practice Skill Vs. Training Output

In line with the idea of internal vs. external stability, we are now faced with practicing a skill and training output.

On the end of the spectrum with internal stability, you have practiced a skill. When we practice a skill, we work on our ability to execute a movement with proper technique, at a certain speed, and under very particular conditions. These sorts of movements require a larger amount of cognitive effort and they should not be taken to failure due to the true intent of the exercise—its neurological signaling and skill acquisition. If we take exercises like these to failure, or if our form starts to decay, we are not only at a higher risk of muddying the signal and developing improper technique, but we could find ourselves getting injured. The limiting factor on these particular exercises is your ability to internally stabilize utilizing your own body, skills, and positioning.

The example I like to utilize for practicing a skill would be something like a clean and jerk to a competitive weightlifter or a competition squat to a powerlifter.

When both of these athletes are training these particular movements, their goal is to build technical mastery to move the most weight. The clean and jerk is a far more technical skill than a barbell back squat, but the idea is the same. This is the portion of your training you want to be able to focus on the most, and it needs to be completed early on in the training session for you to adequately practice and perform the movements correctly.

That is not to say that these movements will not be trained heavy or with high intensity; that is simply not the case. What I'm saying is that the technical mastery of the movements takes precedence over all other variables. At the end of the day, the more proficient lifter will be able to stay in the game longer, avoid more injuries, and therefore get stronger over the course of their career.

Training output would be where you punch the gas. We are not worried about maintaining more complex positions or patterns, and the limiting factor is not our technical skill of the lift. Training output would be where we would put accessory exercises, machine work, or exercises where we are holding on to a rack/bench/etc. The goal is to put as much mechanical tension into the muscle as possible and get closer to true muscular and systemic failure rather than technical failure. These are the type of exercises you would utilize for challenge sets, drop sets, and just good ole fashioned beatdowns on training days.

Putting It All Together

All of this information is really cool and all, but how the hell does it help you get stronger?

This section is the cool part because everything we have discussed so far in this article can help you make better decisions in the gym. Not only with exercise selection but with setting up your entire training plan as a whole. If you can utilize the principles we have gone over, you will find you will be able to get more out of your training and keep the intent of each part of your training session in alignment with the end goal.

Power/Jumps/Throws/Sprints

Power production should be completed earlier on in the training session—due to the greater demand for internal stability within the athlete and the higher level of skill and coordination. In more basic terms, if you're tired or fatigued, you have a reduced benefit of the training and an increased risk of injury from faulty execution. You need to be firing on all cylinders to get the most out of sprints, jumps, and throws if power development is your goal.

Main Movements

Main movements...now, you're paying attention.

If you are a strength athlete, powerlifter, or someone that wants to get really strong, the best place to start your training session is with your main movement(s). In the world of powerlifting, this would be the bench, squat, or deadlift. The focus for this portion of your training should still be focused on maximizing your ability to maintain proper technique and form through greater and greater weight over time. You are building your skill with each lift, and the goal is to perfect that technique as you progress through your training.

This is not to say that this portion of your training will not be difficult or that you will not push the envelope here.

I'm saying that the goal of these lifts is to practice the execution of the lifts themselves. You are working on the skill of the movement, which requires a high level of concentration, focus, and internal stability—exactly why it needs to be at the forefront of your training day.

Supplemental Lifts

Supplemental lifts are where we start to shift from practicing a skill to training an output. They come next in the hierarchy of exercise selection because they help build your ability to better perform the main movements. So, instead of thinking purely about the execution of the movement itself, you begin to focus on pieces of that lift that need to be improved. With that, we begin to shift from movements to muscles and it starts with the supplemental lifts.

We also begin to take some of the internal stability demands away from the exercise so that we can start to train more for muscle growth and overall strength. An example of this would be taking your bench press as your main movement, realizing that you need to work on your lockout strength and triceps, and then jumping into a floor press. The floor press is more externally stabilized in the way that you are laying on the floor, is limited in your range of motion and stability demands, and focuses more on just building your triceps strength. These are higher reps than your main movements (5-8s) and are designed to build up and help support what you did to start your training session.

Accessories

This is where the bodybuilder in us all comes out. This portion of the training day should be focusing more on single-joint exercises, machines, or utilizing externally stabilized means (holding on to a rack, bench, etc.,) in order to get the most mechanical tension, metabolic stress, and even damage to the individual muscles that we are looking to target. We do this by mitigating the need for a larger concentration on technique or position via internal stability and switch over the exercises that provide the stability and positioning for you while you provide the gas pedal and output.

Accessories include the leg press, hack squats, lat pulldowns, seated rows, curls, etc., that help you develop the muscle and tissue you are looking for. At this point in the training session, your ability to maintain complicated technique or positioning is limited and it is time to put your helmet on and just drop the hammer on some less complicated exercises.

Train to failure, implement drop sets and supersets, add in bands and chains, or play with the strength curve. Accessories are also where you'll see Dave and I utilize the diabolical drop sets during the Train Your Ass Off events. We pick a machine or a piece of equipment that allows the athlete to lock in and just focus on driving as much force as they can into the task at hand. In this case, there's less room for error and less of a chance of injury due to fatigue. See? There is a method to the madness.

Conclusion

If this was a bit confusing for you, or it seems overwhelming, watch the YouTube video of me explaining these concepts in a less wordy way. I know that you might be more of a visual or auditory learner, so we have you covered. It is important to realize that this is not the be-all-end-all for exercise selection. It is merely a lens through which to look at your training and how you can better implement the exercises you utilize. Consider these less hard and fast rules as principles for you to make better decisions for yourself and your clients. Take what you find useful and forget the rest.

Sam Brown is a coach at elitefts, developing the next generation of coaches and athletes. Owner of Practice Movement and Recovery LLC, he consults clients to get out of pain and boost performance—one of the few McGill Method Practitioners in the United States. He’s a strongman and competes in the 198- to 200-pound weight class.

1 Comment