The interesting thing about the lifts is that you see them differently depending on how, where, and who you are watching. For example, during most of my “seasoned lifter” life, I trained alone. That is one of the reasons I became a raw lifter. Also, there was nobody around me I trusted with technique critique. That reduced the options to me to watching myself through a camera that videotaped whatever I did.

Is that the best scenario? Hell, no. Nothing beats the experienced, unassisted (meaning no video; glasses are okay) eyes of a good coach.

WATCH: Developing Powerlifters Through the Role and Responsibilities of a Meet Director

There are things you see from other perspectives, though. A video can be treated with computer software that gives you precise data on bar speed, a biomechanics lab that gives you lots of information, a strength platform, an electromyograph, etc. Nobody has the luxury of using these tools in training, though.

One thing I learned is that nothing trumps experience — the sheer number of lifts you watch and analyze.

But wait. Who watches the largest number of lifts in their “occupation?" Bingo, the judge. That poor bastard sitting on a chair will watch between 140 and 180 squats in any given small meet. Try a world championship: it is that number multiplied by four to 10.

General arrangement of a powerlifting competitive platform

If the meet is well organized, the judges will rotate positions (central, side-right, side-left). We know, by experience, that there is a point where the judge will be so exhausted in that position that the frequency of bad calls (everyone makes bad calls; what matters is the frequency) will start to rise.

I’m an international judge with the USPA/IPL. It is not my objective to discuss our procedures or rules. However, I realized that working eight hours judging lifts in one day or about six for four days gives me a privileged perspective on, well, everything.

I will try to share with you what watching thousands of lifts, with the highest level of attention I could muster at the moment, taught me.

I will start with the squat, for obvious reasons.

“The platform is ready.” – The Schroedinger 60 seconds in a box

In powerlifting meets, we frequently use the baseball terminology. For example: "Stevenson is the lifter. West, you are on deck (next) and Perez, you are in the hole (after West)."

Stevenson hears “the platform is ready” or “the bar is loaded” (depending on the sanctioning body). He has 60 seconds to start the lift. If Stevenson is a knee-wrapped lifter (whether equipped or classic raw) three things may happen:

A. He has been wrapped for too long because either his anxiety took over (or his handler’s anxiety took over) or there was some delay in adjusting the rack and the bar. Maybe Stevenson is very short and Peters, before him, was very tall; maybe their attempts are radically different and the loaders have to move too many plates. Many things can happen to slow down the preparation of the platform

B. He is still not fully wrapped. He has the following options:

- Panic and wrap too fast, making one knee tighter than the other, then focus on that, instead of the lift. That’s bad.

- Panic, but wait until he is fully wrapped, rush to the platform, unrack the bar under panic and in a clumsy manner. That’s bad.

- Stay calm, wait until he is fully wrapped, and if the sixty seconds are about to expire, unrack the bar and re-rack it before the “squat” command.

- Either panic or stay calm, but miss the 60 seconds and the attempt. In a catastrophic scenario, also get disqualified, if this is his third attempt following two failed attempts. Leave the platform and move on.

- Either panic or stay calm, but miss the 60 seconds and the attempt. In a catastrophic scenario, also get disqualified, if this is his third attempt following two failed attempts. Go berserk, bang his head on the bar, curse loudly, and get expelled by all the judges and meet organizer, perhaps the police.

C. He is fully wrapped, on time, and...

- He’s too far from the platform and realizes he needs to walk up there with quasi-immobilized knees.

- He unracks the bar, takes two or three short steps back, and performs his squat.

If Stevenson is a raw lifter, some of the items above may happen. But let’s focus on the following:

- He is not paying attention, he reaches the bar too close to the 60-second limit, panic takes over, and his lift is a mess.

- He is psyching up four lifters ahead of time. He’s not even in the hole and he is growling, his buddies are slapping him around, and when he gets to the platform, he is “over-psyched” and his lift is a mess.

- He is either not using earphones or takes them off two lifters before he is called. He is completely focused, confident, he is called to the platform, reaches the bar with plenty of time, and performs his lift.

In any case, Stevenson can have a lot of time or no time. What does that mean? Those 60 seconds are neither a lot nor too little; they are the regular time. Period. Rules are arbitrary things. When we become athletes, we adjust to the rules not because they are the best way to perform something, but because a sport is a game, a game involves competition, and in competition, things have to be standardized by rules.

In 2012, clinical psychologist Dr. Joao Cozac applied a biofeedback experiment on two lifters (me, a powerlifter, and a male weightlifter). He was intrigued that both of us were able to complete a certain task that involved extreme focus in 57 to 60 seconds, whereas the tennis players, fencers, and other athletes he applied the same test to took varying periods, apparently randomly. When he discussed that result with me I suggested that both the weightlifter and I had exactly 60 seconds to perform a competitive lift and that, along the years, depending on how deep the competitor identity goes, our sensory perception is shaped accordingly. In other words, the funneling of sensory input, the inner sequence of resource recruitment, and the heightening and silencing of abilities happen along 60 seconds. Competitive preparedness, for a lifter, means that those 60 seconds exist and don’t exist at the same time, since they will cease to exist the moment the lift starts (it is a “timeless” moment). As a lifter, I felt that.

But as a judge, I observed all possible variations from extreme awareness of the time as being too short from complete unawareness of time.

Highlights:

- Sixty seconds is more than enough time. Make good use of it. Rehearse practical things (like wrapping knees).

- Don’t over-psych and don’t get distracted. This is neither your public beheading or a beer with friends.

The Rack Height

The powerlifting official competition rack follows certain specs for width, height, etc., but what matters here is that they are all equipped with an adjustable upright, numbered holes, and levers to allow loaders to easily set the bar at the requested height. Observe the picture below:

elitefts signature competition combo rack. For the squat, the bench is removed, as well as the face-savers, which are also adjustable; the distance between the adjustment holes is standardized and a pin holds the uprights in place).

If you ever served as an official at a meet, there’s the rack height choice moment. For us (USPA), that’s at weigh-ins, when we fill out the person’s full card. I don’t care: I offer advice. It’s better to offer advice at this point, wearing a green shirt (international judge uniform), then to watch a platform disaster later on. What platform disaster? The rack is too high and, with the bar loaded, Stevenson doesn’t have an average of 120-degree knee/hip/ankle extension to unrack the bar. He panics, hyperextends, does calf raises, or whatever is needed to free the bar from the rack.

There’s no absolute rule for where is the best squat rack height, but as you can see from the picture below, it is a few inches below the shoulder line. For some people, it is a little over the nipples. That is why we measure the rack height before the meet; you must find the best height to comfortably unrack the bar with a powerful knee/hip/ankle extension.

Sometimes up to 30% of the novice lifters have inadequate squat rack heights, and that makes unracking so much more difficult than it may compromise the lift itself.

Nick Tsourounis, USPA National judge, preparing to squat under a Monolift

Unracking the Bar

The item above explains this one: what the central and side judges see from their chair is an individual removing a loaded bar from a rack with uprights set at his requested height. As I said, at least 30% of novice lifters get their rack height too high. As a judge, I have no idea how they trained. But with a bar too high for them, it’s easy to unrack it close to the cervical area, which is dangerously too high even for a very “high bar” squatter.

If the bar doesn’t sit at that lifter’s “sweet spot”, which is where he is able to perform a full range of motion squat with well-coordinated triple lower joint flexion and extension, something is going to be off. The reason is what is called “the line of gravity” — the bar is a body with a given mass that will move down with the kinetic energy converted from the potential energy provided by it having been placed x feet away from the ground. It is vertical.

Those awkward squats with excessive torso flexion for that lifter’s torso length, the visible alignment of the bar with the balls of the feet (or even worse), instead of mid-foot, are frequently issues that began with unracking the bar too high, then panicking, then messing up the whole lift.

The first thing, then, is to make sure the bar is placed where you want it on your back. Have you ever seen lifters spend seconds somewhat “carving” their backs into the bar? That’s what they are doing: making sure the bar is placed exactly where they can “negotiate” the line of gravity with it.

The next thing is to understand that unracking the bar is not unlike a “mini-lockout." You place yourself under the bar with approximately 120-degree lower joint flexion so that a powerful and controlled extension will allow the lifter to stand up, sustain the bar, and start to walk back. Usually, there is one Valsalva maneuver (“big air, big air!”) to unrack the bar, then exhalation, then another one for the squat itself after achieving the start position.

Nick Cambero taking in “big air” to perform his squat. July 30, 2017, at Barbell Brigade, Los Angeles. USPA meet

Bradley Heinss July 30, 2017, at Barbell Brigade, Los Angeles. USPA meet

Bradley Heinss July 30, 2017, at Barbell Brigade, Los Angeles. USPA meet

Highlights:

- Once at the platform, take your time finding your preferred bar placement on the back.

- Unrack the bar with full control, feet under the bar (no lunge unrack), short and powerful extension of lower joints.

- Breath and perform the Valsalva maneuver as you always do.

Walking Back and Reaching the Start Position

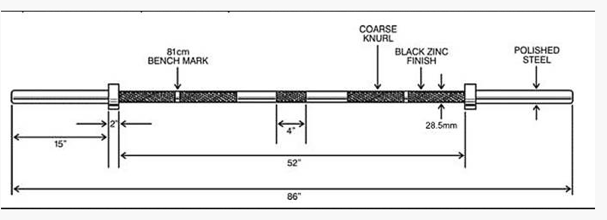

This is a big one. Except in meets with a very select athlete participation of seasoned lifters, the rule is the mile-long back walk combined, or not, with the stability dance. When the meet offers a combo rack and not a Monolift, there is a walk back from the rack to perform the squat. Observe the pictures. This is a Texas Squat Bar:

It is eight feet long, with 57 inches inside the sleeves. In most meets, men will use this bar. In others, a general “power bar” will be used. Here are its dimensions.

No matter how wide-shouldered you are, there is a lot of bar to your right and to your left when you unrack it. That means that the athlete-barbell-system (ABS) is basically a "T", or a pole (thanks to our complete bipedalism) with a cylinder on the top of it, the cylinder being longer than the axis. This is a nice structure to provide wide bar sleeve travel around the axis, creating disaster. You are the axis, so you want to avoid that.

What does a judge see? Examples:

- People unracking the bar on a quasi-sumo stance (basically their final start position) so that no matter how hard they try, some hip rotation is going to happen. The side judges see that bar waving around. It can be scary.

- The “sumo unrack” is when we most often see a wrong rack height. It is clear that the person measured the rack height while standing with parallel feet, but as they unracked the bar with a wider stance, it turned out to be too high.

- Aware that wide steps will cause rotation, the lifter tries to minimize that by taking as many as 10 tiny steps back, sometimes dangerously close to the edge of the platform

- Wherever they end up, it’s a weird place, so there’s a little dance, with many side steps until the lifter feels sufficiently stable. Sometimes this is so exaggerated that the opposite happens: the lifter becomes dangerously unstable and the head judge give a “rack” command so that the lifter may start it all over again, with more stability and safety.

- Sometimes the instability is not as pronounced as to justify a re-rack command, especially if the head judge has already understood that Stevenson is very anxious and has little control of the bar. The result is that he won’t stop shaking and sometimes this is as good as it gets. He is sufficiently locked out, so he receives a “squat” command. I would say about 40% of the shaking-start squats end up good, but it is definitely not optimal.

How do you avoid a walk-back disaster?

- Optimize your axis role in the ABS by unracking the bar with feet as aligned to your shoulders as possible

- Tighten up your hips and brace yourself to minimize hip rotation.

- Take as few steps as you can. Tall people manage even two steps, which are slightly (emphasis on slightly) diagonal so that the final stance is your preferred squat stance. Shorter people take three or four steps. The three-step strategy widens the stance at each step. The four-step strategy is usually a walk back with parallel feet and a two-step stance widening. I personally dislike this last one, but some experienced lifters do that.

- Keep your head straight and don’t look sideways. Ever.

“Dropping” Down

A squat is a powerlift, not a quick lift. A competitive lift is supposed to be close to your maximum effort load. The last thing you want to do is lose control of the descending (or eccentric) phase. Don’t worry, the bar will go down. Newton’s law of universal gravitation ensures that. It also ensures that the bar will accelerate down at 9.8 meters per second squared (m/s/s). That’s fast. Your role is to decelerate the bar on its inevitable way down so that it ends, at the bottom, exactly where you want it to be in order to start using your strength to apply force and accelerate it back up.

What do judges see? Many, if not most, novice lifters allow the bar to decide what to do; they just drop along. Since they can’t manage that much weight yet, it doesn’t break anything in their bodies, but frequently gets them off-balance. Having reached the bottom off-balance, pushing the bar up again becomes a pendular strategy of “negotiating” back the line of gravity. Hips and knees alternate back and forth until either the excruciating upward motion is completed or it just fails.

During this clumsy process, sometimes the bar goes down and, as you know if you are a powerlifter, any downward movement of the bar while ascending gets a red light.

Sometimes the upward motion is so unstable that once reaching the standing position, the lifter has to take a step in order not to fall before receiving the “rack” command. Red lights.

Highlights:

- Listen to the commands! You may only start the downward movement after you receive the “squat” command. Once you've finished the upward movement you may only move after the “rack” command.

- Control the bar on your way down until you feel you reached the accepted depth. This is not a paused squat. Don’t stop there. Immediately start the upward motion, making use of whatever elastic energy you have.

- Don’t jerk the bar. Again, stability is the mother of strength. Keep it under control until you reach the final position, with locked knees and hips.

USPA judge Jeffrey Winkler finding a position for the best view of the squat from his right-side place. USPA Hardknox Third Annual Powerlifting Meet, 6/17/17, Brownsville TX

Good luck!

Header image courtesy of USPA Texas State Judge Jeffrey Winkler as the central referee meet: USPA Hardknox Third Annual Powerlifting Meet, 6/17/17, Brownsville TX