Introduction: How We Think Stuff Works and How Stuff Really Works (or Doesn’t)

The knee sleeves article is the fourth in the personal equipment series: the first was the belt, the second was the wrist wrap, and the third was the knee wrap, a bit more controversial than the first two.

Knee sleeves have deserved little attention from the scientific community and a lot of patenting activity from manufacturers. The products are not niche-restricted and are growing in complexity, variety, and possibly efficiency.

In spite of the scarcity of research, the level of controversy is remarkably lower: apparently, there is no disagreement concerning the claim about the proprioceptive improvement provided by knee sleeves. The assumption that there is a causal relationship between this effect and the observed benefits concerning injury prevention and better movement, in general, is also undisputed although everyone agrees that more research is needed into the mechanism itself.

Among the almost 300 users that responded to my survey, there is clear uncertainty and unawareness about why sleeves are nice although most users think they are. This was unsurprising: users are not expected to know the science behind a product's effects. There are less clear assumptions concerning sleeves than the previously examined personal equipment items, though.

There’s an almost universal agreement about how smelly they can get (especially the neoprene ones). Unlike the scientific evidence for the mechanism of the sleeves effects, there is not even a little bit of consensus on how to get rid of the smell. For those of us who handled very expensive lifting gear that could get nauseatingly stinky, it’s a walk in the park. With gear, some people just avoided washing them at all in fear that any method would damage them (these people were difficult training partners). It’s not true: it’s synthetic fabric, that’s all. Neoprene is spongy synthetic fabric, which makes it a great culture medium for bacteria and fungi when soaked with sweat, fat and skin debris. Some people even boil them and according to their accounts, they come out of the ordeal in perfect condition. For those too concerned, soaking and washing them in water with soap for delicate clothes will work.

Basics About the Knee Wrap

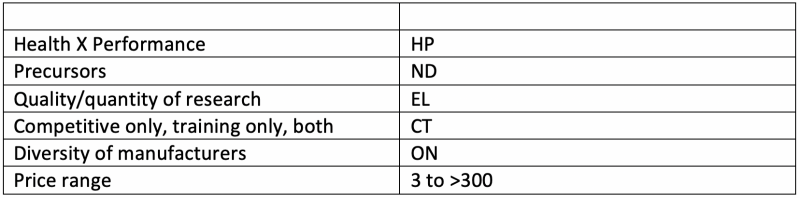

Summary chart:

What Does a Knee Sleeve Look Like?

I had quite a collection of knee sleeves from my running days. I usually ran 10K races and sometimes longer ones. Like many people, I developed “runner’s knee” or chondromalacia patella. The physicians I saw told me the sleeves were useless. I still had the impression that it was more painful without the sleeves and sometimes only painful when not wearing them.

It turned out that the culprit was not the race, the training for nor the shoes: I had an abnormal and rare meniscus. I was operated on by the president of the knee surgery society with a pack of doctoral students and residents around. After a few weeks of physical therapy and strength tests, he cleared me to run with the following advice: "Dear, I know a lot about knees and nothing about resistance training. But I do know that you will have to start now and never, ever stop. Until you die. The only thing that will keep your knees well is strength training”.

That’s when I started lifting weights and, sure enough, never stopped. My knees never bothered me again, even when I eventually destroyed the left one in an accident, had ACL reconstruction surgery and had most of my meniscus and cartilage removed.

Eventually, I started to train the Olympic lifts. When the bar knurling brushed against the ACL surgery scar it felt like rubbing into raw skin. I dug out my old running sleeves and started wearing them to lift. Being a sumo deadlifter, the knurling didn’t bother me during the powerlifts but as soon as I introduced RDLs and conventional deadlifts I needed the sleeves.

As a raw lifter, I started being contacted by manufacturers for input and got a collection of lifting sleeves. I believe I tested all the main brands who sell to the lifting community. Both my physicians and I believed the sleeves were useless as a performance enhancement device and I just smiled when I saw lifters squeezing themselves into uber tight stiff sleeves.

That was when I had a writing assignment about knee sleeves and found out about their proprioception improvement property (see below). It all made sense to me then: that’s why my knees bothered me less when running and why my squats were more stable when using knee sleeves.

There was always a greater variety of medical knee sleeves in the market. What we can now find is a class of sleeves that offers benefits both to exercise and to injury prevention and treatment.

This is part of my old collection:

Check the knee sleeves from the elitefts online store.

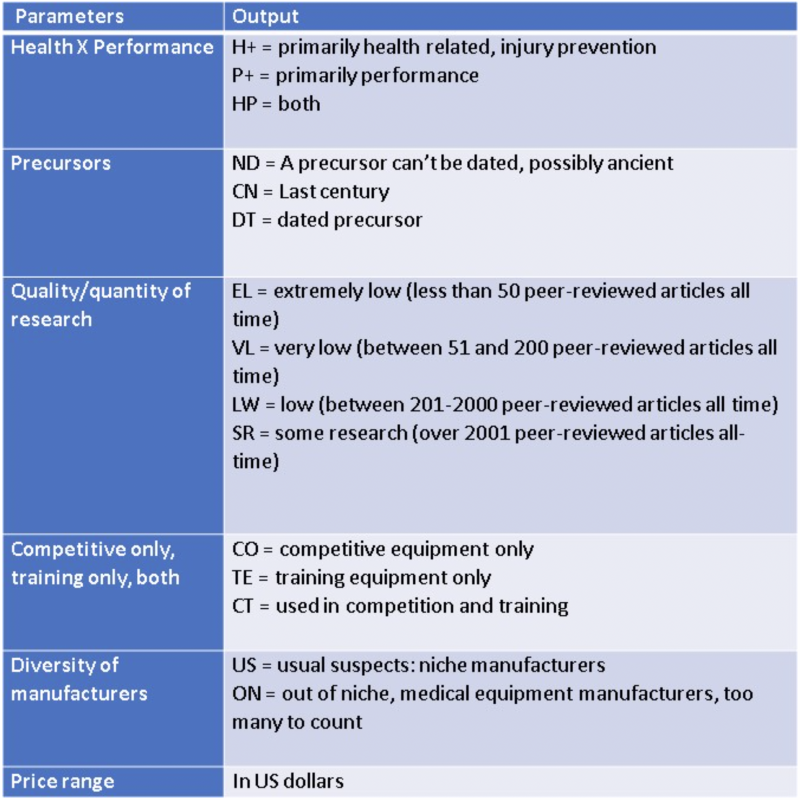

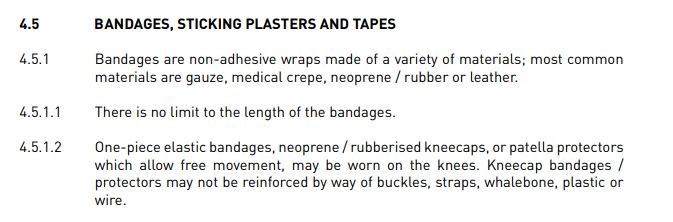

Competition Knee Sleeve Specifications:

Olympic Weightlifting

According to the International Weightlifting Federation, knee wraps, wrist wraps, and knee sleeves fall into the category of “bandages”.

Here are some examples of knee sleeves worn by Olympic Weightlifters in competition thanks to Hookgrip’s wide coverage of the Weightlifting world.

Powerlifting

According to the International Powerlifting Federation:

Besides the specifications, the IPF and few other powerlifting organizations have a list of approved manufacturers that pay a registration and annual fee for each approved item.

Other powerlifting sanctioning bodies do not have such manufacturer approval restriction but the specifications are not that different.

From the IPF Instagram account:

From Startingstrongman Instagram account:

Precursors and Technological Innovation Paths

The precursors of athletic knee sleeves are the same as those of the knee wrap, already reviewed in my previous article.

The State of the Art

There is very little research on knee sleeves. A Pubmed search with the title term “knee sleeves” OR “knee sleeve” resulted in 17 articles, the first one published in 2003. A second search with the same terms for title and abstract resulted in 44 articles, the first one from 1991. By 1996, the chief hypothesis concerning the effect of compressive knee orthoses had already been advanced: proprioception (McNair et al 1996)

Research about knee sleeves, like all research about equipment, derives from two knowledge production forces, an inside force (“science push”) and an outside force (“market pull”). The science push comes from a line of study concerning the effect of compressive knee orthosis. The Pubmed search defined by (knee[Title]) AND (orthoses[Title]) OR (knee[Title]) AND (orthosis[Title]) resulted in 102 articles, the first of which was published in 1975. The publication curve only shows signs of a stable increase after 2005, though.

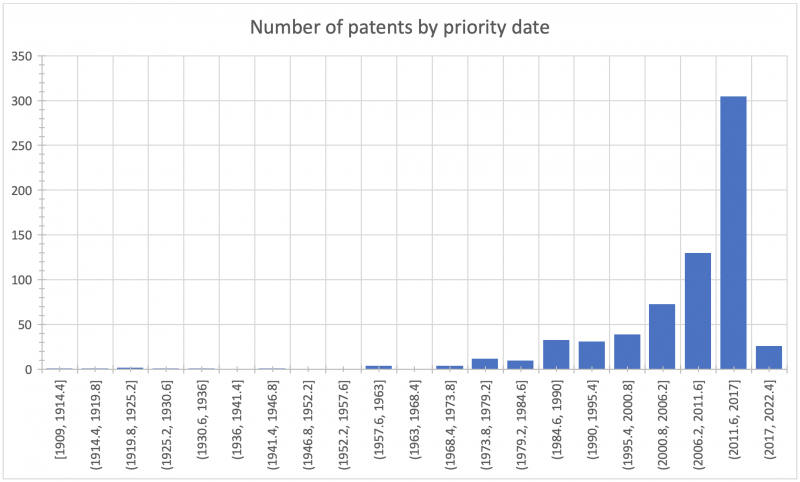

If we compare the science production trend with the patent priority date, with the search term “knee sleeve” on Google Patents, the role of the market pull is evident. There are patents as early as 1909:

Number of patents by priority date with the search expression “knee sleeve” on Google Patents

What does this mean? That before the scientific community was researching a mechanism of action, if any, of knee sleeves for any beneficial purpose, the market was producing them for the same reason it produced medical bandages before.

In 1996, McNair and collaborators (McNair et al 1996) measured the effect of using a knee compressive brace without the hinges (defined as a “sleeve of velfoam”) on a tracking task in a Kim-Com dynamometer. Their objective was to test a hypothesis to explain the improvement in knee injury statistics reported in epidemiological studies from as early as 1986, as cited in their article. The authors hypothesized that the protective effect was a result of improved proprioception. The results of the study supported that hypothesis, with an 11% improvement in tracking performance under braced conditions.

During the 1980s, as cited by McNair and collaborators, a beneficial effect of wearing knee sleeves was observed mostly in college football. Sleeves were already commercialized at the time but it was only in 1996 that a mechanism was proposed.

In the period between 1995 and 2000, there were 39 patent applications at the USPTO.

A literature review published in 2017 (Sharif et al 2017) concluded that "most improvements were observed in: proprioception for healthy knees, gait, and balance for osteoarthritic knees, and functional improvement of injured knees" but, as always, “further work is needed”.

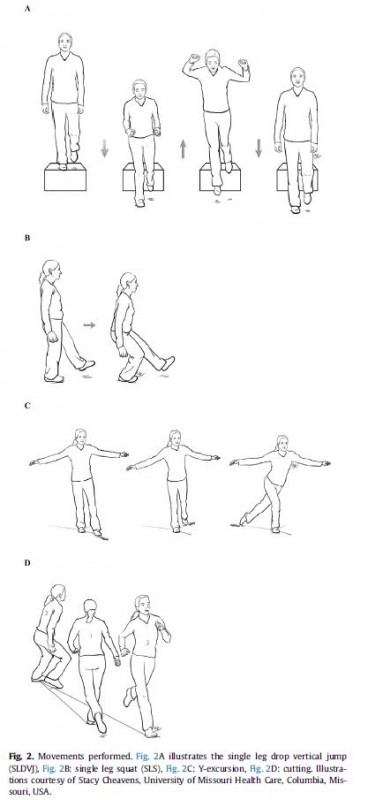

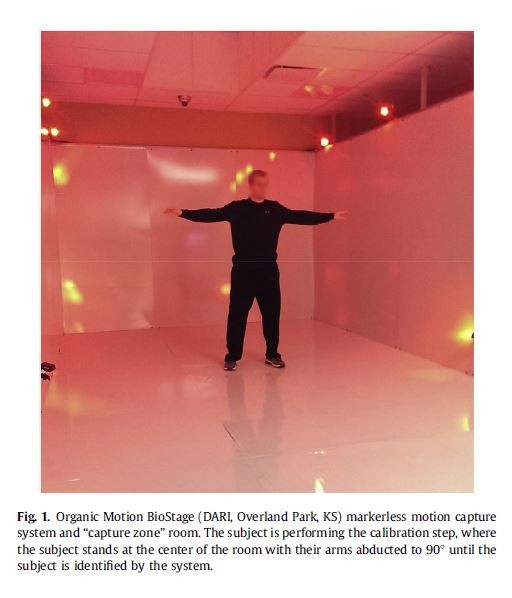

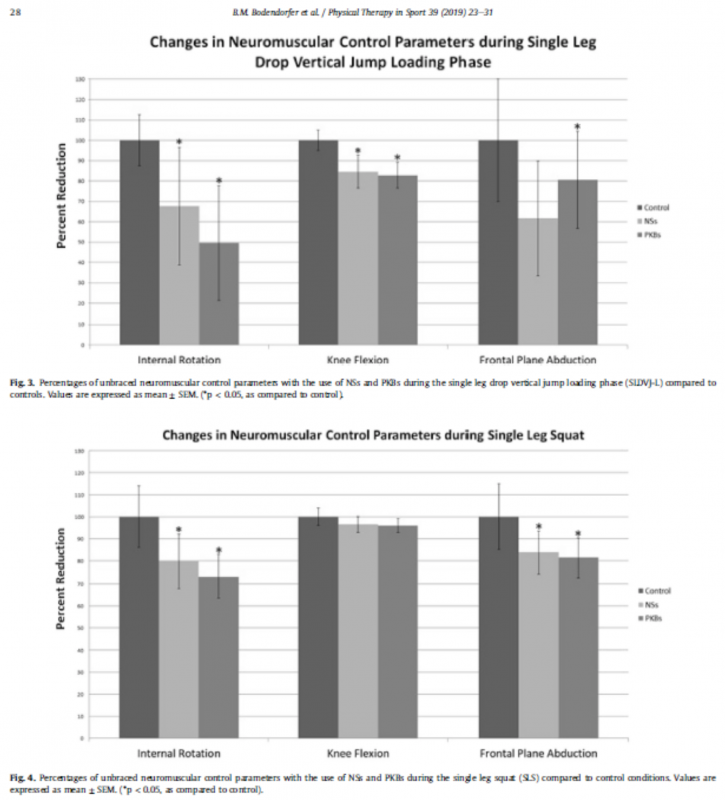

The most recent study on knee braces and sleeves refers to the neoprene sleeves as “proprioceptive braces” (proprioception defined as “the capacity for one's central nervous system to detect changes in joint kinematics”). The study examined the effects of knee braces and sleeves on neuromuscular control (“the ability to maintain dynamic joint stability”) in a motion laboratory using the following movements: single-leg drop vertical jump, single-leg squat, Y-excursion and cutting.

From Bodendorfer et al 2019.

From Bodendorfer et al 2019.

The authors concluded that “NSs (neoprene sleeves) and PKBs (prophylactic knee braces) significantly reduced hip internal rotation, knee flexion, and knee FPA (frontal plane abduction) during movements that required significant neuromuscular control without affecting cutting agility. Decreased hip internal rotation and FPA may decrease dynamic valgus of the knee and thereby may protect against noncontact ACL injury” (Bodendorfer et al 2019).

From Bodendorfer et al 2019.

Previous studies, most corroborating and elaborating on McNair and collaborators’ early hypothesis but pointing out that “more research is needed” include: Birmington and collaborators’ study on kinesthetic ability improvement by neoprene knee sleeves (2000); Herrington and collaborators’ study showing an improvement of proprioceptive acuity with the use of neoprene sleeves (Herrington et al 2005); Sinclair and collaborators’ study showing that both average and instantaneous ACL load rates were significantly reduced when wearing the knee sleeve in the hop and cut (Sinclair et al 2019); and Csapo and collaborators’ study concluding that the knee sleeve reduces anterior tibial translation in healthy subjects, increasing their stability (Csapo et al 2016).

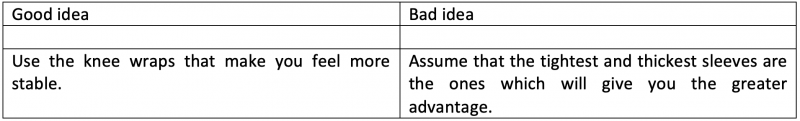

Studies also examined the effect of knee sleeves on muscle activation, 1RM, and rate of perceived effort, concluding that they offer no gain in these indicators (Trypuc 2018). Making sleeves stiffer, thicker and using them as tight as possible may have no strength carry-over.

Finally, the popular idea that knee sleeves are “good” (to prevent injury or improve performance) because they keep the knees warm has no support from research.

How Do Athletes Use the Knee Sleeve: The Survey

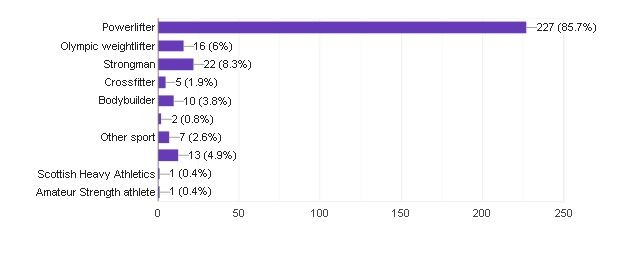

I created a survey about knee sleeve use for athletes and regular weight training people. There are 266 responses, the great majority of which being from powerlifters.

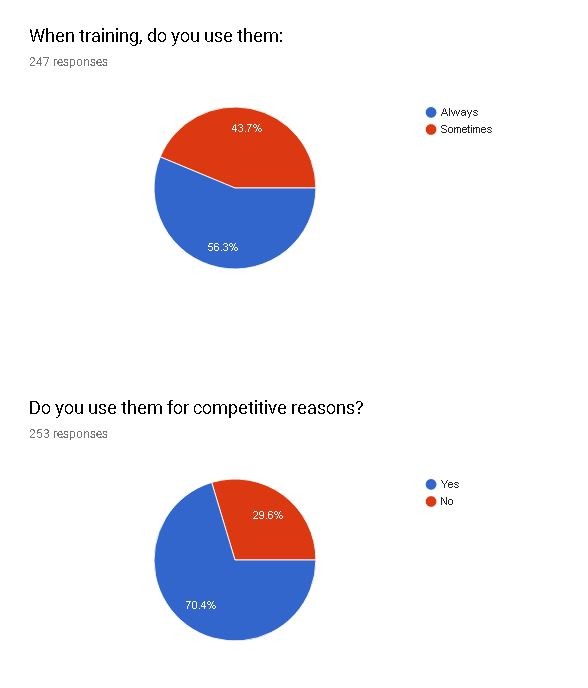

The sex (63.4% male) and age (from 17 to 74 years old) distribution reflect what is expected from strength training practitioners, whether competitive or not. Most of the respondents either use and own knee sleeves (85.6% use them and 92.9% own their sleeves) and only 14.1% declared using them for medical reasons.

The majority of respondents owns one (35.9%) or two (32.2%) pairs of sleeves but a significant percentage (13.9%) owns three pairs.

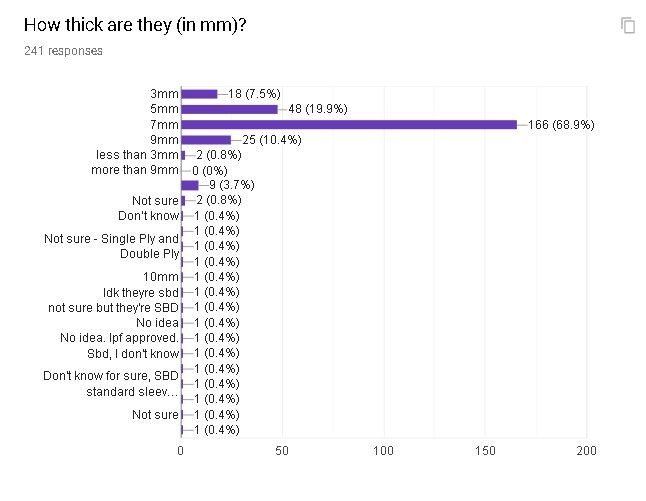

The vast majority of respondents owns/uses 7mm thick sleeves (68.9%). The popularity of that thickness is followed by the 5mm, 9mm, and 3mm thick sleeves.

The preferred brands are, as expected, the ones in the approved list of powerlifting competitive sanctioning bodies. This result is skewed this way due to the prevalence of powerlifters in the respondent pool. It would probably be different if I had reached a proportional number of Olympic Weightlifters and Crossfitters.

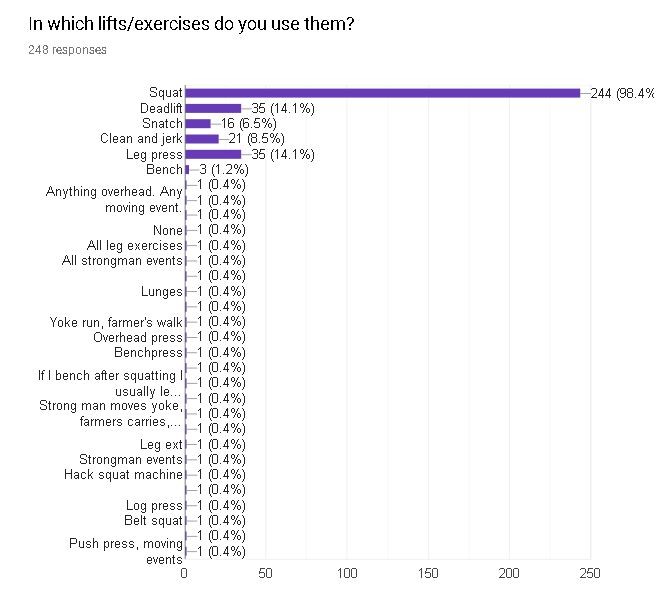

The same trend is seen on the exercise in which the sleeves are used, with the squat dominating the choice, followed by the deadlift and the leg press. Again, had I reached more Olympic weightlifters it would be different.

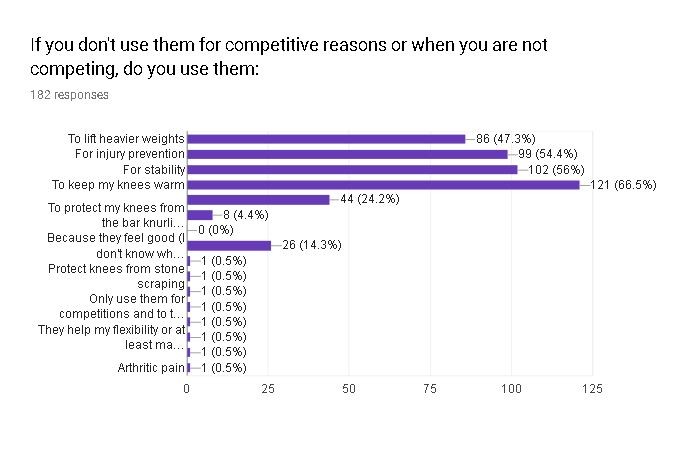

The results suggest that these respondents value the non-competitive benefits of wearing knee sleeves.

The survey shows that the majority of respondents feels, for some reason (unsupported by evidence) that their knees should be kept warm and that the sleeves provide that. The second most popular reason is “for stability”, followed by “injury prevention” and “performance”. It is noteworthy that 14.3% of respondents chose “because they feel good (I don’t know why)”. I added this option because I am aware that most strength training practitioners are unaware of the scholarly consensus concerning proprioception (and now neuromuscular control) as the cause of most benefits observed with the use of knee sleeves by athletes. I do know that being stable “feels good”.

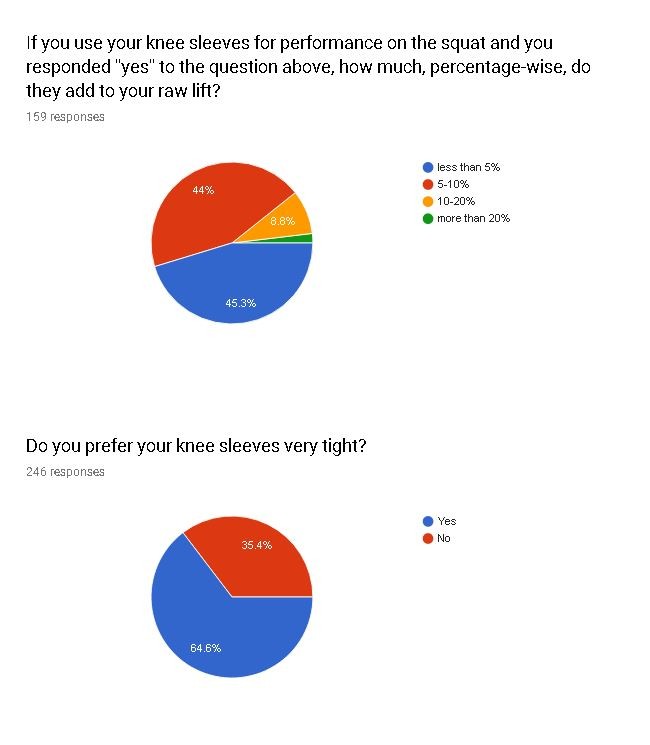

A small majority (51.8%) of respondents believes the sleeves add weight to their lifted weight on the squat (have a carry-over effect). Although Trypuc’s study (2018) shows no effect on 1RM and RPE, stability is an important component of strength and power output. The respondents’ perception, therefore, is not wrong. The percentages of those who don’t believe it has that effect or who are not certain about it are significant.

The perception of carry-over percentage and the preference for very tight sleeves are important pieces of information for future research. Although we know that proprioception improvement is a determinant factor in the beneficial effect of wearing knee sleeves, the effect of improved proprioception on performance still needs more research. Finally, although we know compression is what causes improved proprioception, we don’t know how much compression is optimal for this effect.

Several respondents emphasized the psychological effect of having sleeves covering their knees. We don’t know how much of this perception is visual (“my knees are covered, that’s good”) and how much is the result of proprioception improvement (“my knees are covered and I feel they work better this way”).

One among almost 300 respondents was well aware of the proprioceptive improvement effect.

Bottom line: “know thyself” (again).

References

- Birmingham, TREVOR B., J. TIMOTHY Inglis, JOHN F. Kramer, and ANTHONY A. Vandervoort. "Effect of a neoprene sleeve on knee joint kinesthesis: influence of different testing procedures." Medicine and science in sports and exercise 32, no. 2 (2000): 304-308.

- Bodendorfer, Blake M., Nicholas R. Arnold, Henry T. Shu, Emily V. Leary, James L. Cook, Aaron D. Gray, Trent M. Guess, and Seth L. Sherman. "Do neoprene sleeves and prophylactic knee braces affect neuromuscular control and cutting agility?." Physical Therapy in Sport 39 (2019): 23-31.

- Csapo, Robert, Simona Hosp, Ramona Folie, Robert Eberle, Michael Hasler, and Werner Nachbauer. "Elastic knee sleeves limit anterior tibial translation in healthy females." Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 15, no. 1 (2016): 206-207.

- Herrington, Lee, Claire Simmonds, and Julian Hatcher. "The effect of a neoprene sleeve on knee joint position sense." Research in Sports Medicine 13, no. 1 (2005): 37-46.

- McNair, Peter J., Stephen N. Stanley, and Geoffrey R. Strauss. "Knee bracing: effects on proprioception." Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 77, no. 3 (1996): 287-289.

- Sharif, Nahdatul Aishah Mohd, Siew-Li Goh, Juliana Usman, and Wan Kamarul Zaman Wan Safwani. "Biomechanical and functional efficacy of knee sleeves: A literature review." Physical Therapy in Sport 28 (2017): 44-52.

- Sinclair, Jonathan, and Paul J. Taylor. "Effects of a Prophylactic Knee Sleeve on Anterior Cruciate Ligament Loading During Sport-Specific Movements." Journal of sport rehabilitation 28, no. 1 (2019): 1-7.

- Trypuc, Alexandria A. "Effects of Knee Sleeves on Knee Mechanics During Squats at Variable Depths." (2018).

Lots of information here. I think you might lose some of your audience.

Getting to a summarizing conclusion, a little sooner would be an area to improve on.

First of all, thank you very much: I've been playing with formats for the past two years. Since unfortunately strength and conditioning and exercise in general hasn't benefited from the proverbial "bridge between science and practice", the more educated (but not specialist) audience is left with either a pile of controversial primary sources or superficial and biased general-audience articles. My challenge is to offer dense, respectful, evidence-based content in plain language, to the general audience. Any suggestion is more than welcome (have my email: marilia@mariliacoutinho.com).

I thought about what you pointed out and how to go around it. In another outlet I write science reviews for, I opted for a "summary" with the list of topics hyperlinked to their content so that the reader doesn't have to follow the text linearly. Another strategy I use is, at each topic, to include one sentence that summarizes the whole topic right under the sub-title, in a text box or highlighted in a different color (because it doesn't belong to the linear text).

Science education pieces, if directed to a wide audience, are always a challenge. We have people interested in different aspects of the general subject.

I've published peer-reviewed articles all my life and then it came to technical books. For my books, I decided to include very detailed "content pages". At first, it might look intimidating or "too much information". It works, though: since it's not a hypertexted material (paper), there's no other way to indicate to the reader what they will find in the topic.

It's always a challenge. This "personal equipment" series is organized always in the same order of items: intro, what it looks like, competitive rules, technological precursors, state of the art (small science review) and survey results. Each one could be an independent peer-reviewed article and I am being encouraged to spend some time writing those. The surveys generated a lot of data. The objective with the series, though, is to turn it into an ebook (or book) after the final item.

Please feel free to make suggestions any time.

yours,

Marilia

Minha percepção prática é que a maioria dos praticantes utilizam esses equipamentos como “quem segue a manada”.

Meu relato pessoal (logo não representativo) particularmente não uso cinto, faixa, munhequeira, joelheira.

As raríssimas vezes que o tentei, percebi que a eficiência na exceção dos movimentos ficou prejudicada.