I recently achieved one of my lifelong lifting goals of benching 220 kilograms (485 pounds). You will get a lot of conflicting information on the internet about what is achievable as a lifter, and a lot of the people who read this will probably believe that elite levels of strength are solely determined by natural ability and genetics. What I want to show through this two-part article series is how you can manipulate training variables over time to help you realize your lifetime training goals.

YouTube

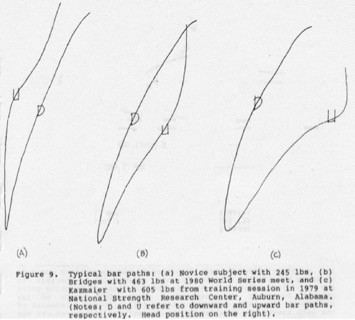

Training in a lot of ways is like a supplement or a drug: how and when it is applied is hugely important.

For a new person lifting weights, simply training is a very potent stimulus. Pretty much any dose of training has the desired effect of making them stronger. As with any other drug or stimulus, the more you use it and the more you do it, the more you blunt the dose/response curve. This means we need more of the same thing or we need to change how it is administered to get a similar response.

We can argue all day long about the effects of supplements, sleep, and food on a lifter’s ability to progress, but we would be wasting our time. As long as you are meeting your caloric needs and are getting enough sleep every night, training is by far the most important thing you have to get stronger. Against it, everything else is noise.

All I want to do is expose you to the concept of training response. I don’t want to get too bogged down in the theory; what I want to concentrate on is the practicality of the matter. As such, we shall now progress on to a case study of two lifters reaching five plates on the bench press.

If a picture is worth one thousand words, then context is worth one million.

The Story of Two Lifters Making It to a 220 kg Raw Bench

One of my lifters—the one who I have been coaching for the longest time consistently out of anyone—recently benched 220 kg (484 pounds) at a bodyweight of 140 kg (308 pounds). This naturally was all the motivation I needed to break through the five-plate barrier. The way my training had been going, I knew my max was well above my previous best of 210 kg (462 pounds), but I hadn’t maxed out in a long time because I was just going through the training process.

Well, needless to say, a training partner getting better than you is normally all the offense against your ego you need to get the stupidity/motivation you need to push on.

I’ve always had a relatively strong bench press. It took about four years of training before I benched 185 kg (407 pounds) at 206 pounds bodyweight. However, once I reached 200 kg (440 pounds) my bench press slowed down to a crawl and it took a lot of changes to my training and advances in my knowledge and application to get the last 20 kg (44 pounds) out of my bench press.

Alistair, the lifter who I referred to earlier in the article, is a friend who is a freak on the other two lifts (squatting 340 kg/748 pounds and deadlifting 350 kg/770 pounds), but has always been a weakling on the bench press (relatively). Ali’s best bench press in competition was 190 kg (420 pounds) in 2013. In the gym, the best he had pressed was 210 kg, slow. He spent about two years making little to no progress until I took over his programming again at the end of 2015 and changed a few factors, which led to him pressing 220 kg (more on this in the next article).

The weekend after Alistair benched 484 pounds, I maxed out and benched 488 pounds at a bodyweight of 257 pounds, which was a 26-pound increase on my previous gym max. I had been capable of around this press for a long time but didn’t want to realize it in training. What follows is how we practically went from benching on an intermediate level to making it to five plates.

Going From 0 to 400

Let’s face it: not all of you who read this article are capable of bench pressing five plates a side. For some of you, it’s just not meant to be. However, that’s not to say you can’t use the principals and ideas presented in these articles to get closer to your own genetic ceiling a bit faster.

Get Your Technique Down

There are a number of videos and articles on how to set up your bench press technique. For my money, the best one that puts across how to bench as a raw lifter is the super training video with Eric Spoto. There are a number of points of detail, such as how a lifter's elbows should travel relative to the bar, that a lot of bench press tutorials from good equipped lifters miss the boat on.

RELATED: The Physics of the Bench Press: Science Applied

Getting your technique down also involves some feedback, so taking video of you lifting from the side and paying attention to your bar path is extremely important for seeing if your bench press is efficient.

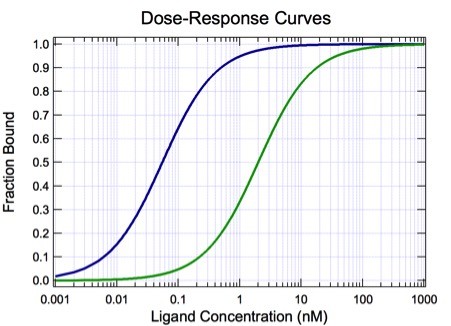

Source: Chris Duffin

As you can see from the illustration above, more advanced lifters exhibit a more distinct separation between the downward and upward path of the barbell. While we may not want to exhibit any of these bar paths exactly, what we can see is that there should be some distinction between coming down towards the chest and pressing the bar back up.

As you bring the bar down, this is what you are trying to achieve:

- Control where the bar is going at all times to ensure you can get the press you want from the chest.

- Expend as little energy as possible to ensure you have as much concentric power as possible to put into the bar when you press it. This will either make lighter weight relatively easier or allow us a better chance of pressing a new max or heavy single.

- You want to bring the bar down to the spot on your body that allows you to produce the most torque as possible on the bar.

Once the bar is on your chest you should be looking to achieve the following:

- Engage your glutes, push your upper back through the bench, and drive your heels through the floor, all at the same time. If you get this coordinated correctly, you will get much better speed from the chest and should find that you get into a better position from which to lock out.

- Push the bar back towards your face/the rack. This will help you engage your lats at the bottom of the press, which allows you to keep your elbows under the bar, which means you can act on it longer, using the chest/triceps. Having the bar come up your chest by flaring your elbows puts the weight towards your shoulders, which is by far the weaker muscle group.

- If you get the timing of the drive correct, the bar should fly towards the sticking point. At this point, the majority of the stress moves towards the elbows and triceps. At this point you should continue to think about pushing yourself back into the bench and pushing your elbows together until lockout.

Get Your Programming Right

Before you get excited, I am not about to give you the exact training cycle that is going to bring you from benching the bar to benching 400 pounds. However, what I am going to talk about are key elements your program should have at this stage of your lifting career.

It is very difficult to get better at the bench press without doing a lot of bench press. As such, you can give yourself the best chance of benching your potential by practicing the movement you want to get better at.

Bench press variations are important but it’s still an overriding imperative that at least 70% of your bench press volume is spent practicing how you play. This means if you compete in powerlifting raw, you should train bench press to the same conditions you will do them in a meet. Similarly, if you compete in single-ply or multi-ply, you should bench in the shirt for roughly 70% of your bench pressing volume.

These general guidelines will become more clouded as you progress as a lifter. However, from the beginner to an advanced stage, if you follow these guidelines you’re going to see some pretty fantastic progress:

- Bench press with a frequency of two to three times per week. If you bench three times per week you should look at having two variations in your program and doing less assistance pressing work. If you bench press one to two times per week, you should do a good amount of pressing assistance work.

- Utilize a good volume of training and cycle it throughout your program. These aren’t by any means the only training volume guidelines you can utilize, but they will be a great starting point: High Volume Week – 50 total lifts, Medium Volume Week – 30-40 total lifts, Low Volume Week – 10-30 total lifts.

- Plan your training using a reasonably linear approach. You can jump on more undulating programs, but there isn’t any need to start breaking out the aces just yet. You will get lots of success using three to six week training cycles that start with a period of high volume and work towards a period of lower volume and higher intensity.

- Work backwards from your target. At this stage in training, splitting your training year into targets is a great idea. If you’re currently benching 225, there is no reason you can’t bench 275 or 300 in the next 8-12 months. Start setting some time frames on it and work backwards from your target. For instance, if you want to press 290, you’re going to have to press 275x2, 260x3, and 250x4.

- Focus your pressing volume on related exercises and target areas. If you are long-armed, close grip or board work is of great importance, because your triceps are going to be involved for longer than most people. If you press with a flat back or your form isn’t very stable, incline is excellent for building off-line strength. Understand what kind of lifter you are and tackle it with the correct tool kit.

- Use the 80/20 rule for your assistance work. 80% of your time should be spent trying to get better at bench press. The next 20% should be spent on working on general muscular conditioning of key areas, namely rear delts, lats, rhomboids, rotator cuffs, lower traps, and shoulders.

- As a beginner, you need to go hard on a regular basis. Now, I’m not suggesting you max out every week, but maybe one week in every three or one block in every three, you should look at overload. Something like AMRAP sets after volume or just simple old pyramid sets trying to go as heavy as possible will work for this. This kind of training should be carried out for a finite time and with precursor volume to feed off. Doing this week-in, week-out is a one-way ticket to snap city. But as an intermediate to advanced lifter, you can get some absolutely fantastic gains off it.

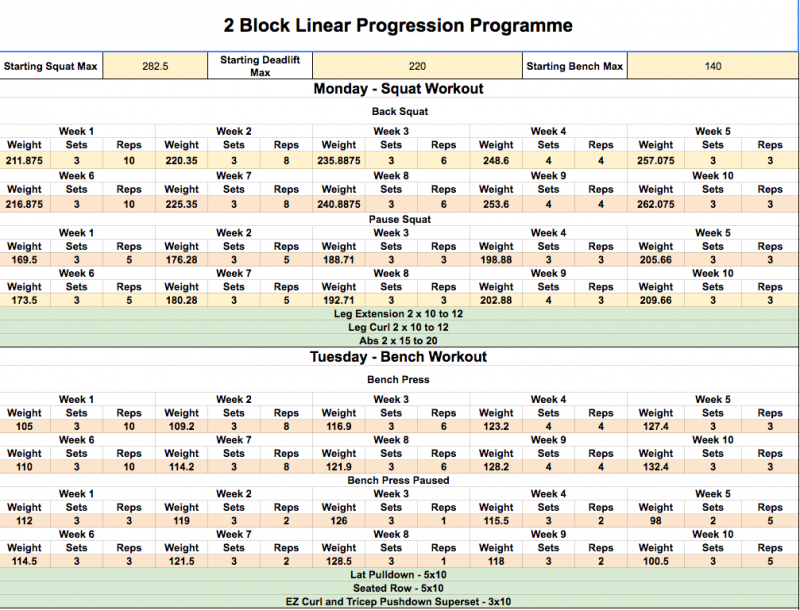

Two Training Programs

Let's move on to two training programs you can abuse the crap out of to get better at bench press during this stage of your training. As we mentioned earlier in the article, at this stage in training there is no need to get dragged into DUP or any other more nuisance or targeted programming methods. Just showing up and putting the graft in using a simple and effective program will do all the work you need. Below are two programs I have used to help at least 100 lifters bench over 140 kg (308 pounds) and 50 lifters bench over 160 kg (350 pounds).

The 5-Week Linear Cycle (Modified/Stolen from Ed Coan’s Competition Build-Ups)

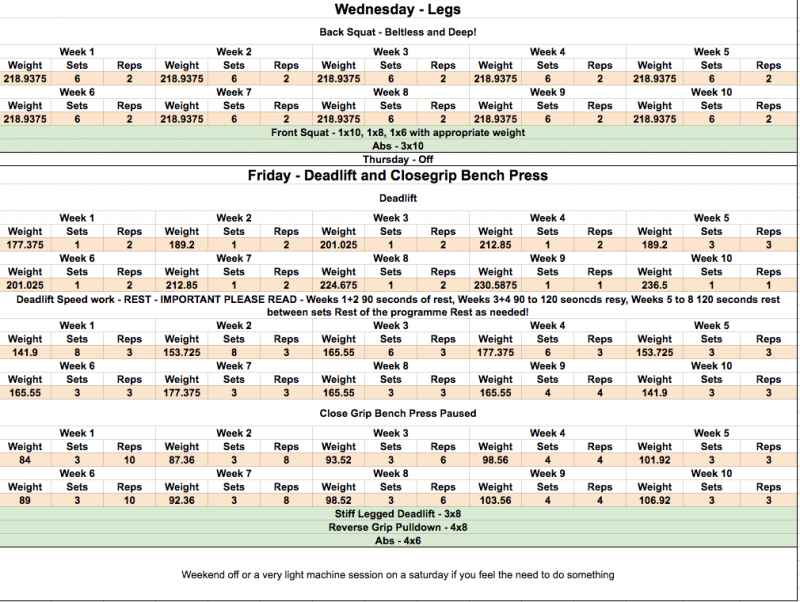

The main program is once per week and works using the following volumes and percentages:

- Week 1 – 3 sets of 10 with 75% RM

- Week 2 – 3 sets of 8 with 78% RM

- Week 3 – 3 sets of 6 with 83.5% RM

- Week 4 – 4 sets of 4 with 88% RM

- Week 5 – 3 sets of 3 with 90% RM

For assistance, you should look to apply the same sets x reps on a second day to incline bench press or shoulder press also with the addition of three to four back exercises following a hypertrophy protocol (3x15, for example).

A calculator for the full program:

Use the spreadsheet version to access your own copy that you can edit. Simply access the file menu and click "make a copy."

The Cast Iron Pressing Template — A Slightly More Refined Meathead Method

Day 1

- Strict Press: Base Set/Heavy Reps Set/Optional PB Attempt/Down Set

- Close Grip Press: Build up in fives to PB Attempt Set

- DB Shoulder Press: Two Heavy Rep Sets (8-12 rep range)

- Bodybuilding: Triceps Work

Day 2 (Three Days Removed from Pressing Day 1)

- Bench Press: Base Set/Heavy Rep Set/Down Set/Pump Set

- Incline Barbell or Dumbbell: Two Heavy Rep Sets (8-12 rep range)

- Bodybuilding: Chest Work

Key

Base Set: This is a starting weight that you are looking to get up to 9-10 reps over the coming few weeks; when you start, this weight should be a very hard 6-7 rep weight. Over the coming weeks, you will try and add a rep or two to this and the following sets.

Heavy Set: Add 45 pounds for the bench press and add 20 pounds for strict press. You are looking for 1-3 reps. When your base set is at 9-10 reps, you will be knocking out 3-4 reps.

Down Set: Reduce 45 pounds from base set for bench press and 10 kg (22 pounds) for strict press. You are looking for 10+ reps on this.

Pump Set: 10 to 20 kg (22 to 44 pounds) from down set, and keep going till your chest falls off.

When the Base Set hits 9-10 reps, add five kilograms to all sets for the next session. If you find you are stalling on a weight two weeks in a row, reduce the weight by 10 pounds. Work it three weeks of loading and one week off. The off week can either be a max week or total rest. Do not perform ANY volume in the off week.

In 2011 this pressing template took my strict press from 195 pounds to 290 pounds, my bench press from 350 pounds for five reps to 398 pounds for five reps, and my top end on the bench has gone from 398 pounds to 445 pounds in eight months. My competition bench PB has gone from 365 to 420 in the same time frame with absolutely no specific work.

The program has worked for hundreds of other lifters who have taken it from my blog or with whom I have worked with in-person.

Originally published in 2016.

Marc Keys is a professional strength and conditioning coach for Edinburgh Rugby. Prior to working in professional sport, Marc worked for the Scotland Institute of Sport where he was involved in the physical preparation of around 60 Olympic and commonwealth athletes from over 20 different of sport, many of whom went to medal for Team Scotland or Great Britain. As a powerlifter, Marc has been lifting in the IPF for eight years. He has competition-best raw lifts of 620-pound squat, 455-pound bench press, and 660-pound deadlift at a bodyweight of 248 pounds. Marc is involved with the training of nearly 100 strength athletes through his online coaching service (onlinestrengthcoach.com) and his barbell club (Edinburgh barbell). If you would like to contact Marc please email speedpowerperformance@gmail.com.

Just to clarify for me: did you use the second template with bench specialists or did you compete in full powerlifting meets? I'm fully aware that I need to back off my squat and deadlift work but do you have any recommends how to design a third day to keep my numbers without a significant drop? Iam a raw lifter (80kg) and my bench sucks hard mainly because not focusing on it too much in the past. My best competition lifts are 185kg/105kg/230kg.

Thank you for your help,

Tom

I would just run an upper/lower split easy.

Day 1 - Squat & Assistance

Day 2 - Pressing template session 1

Day 3 - Off

Day 4 - Deadlift & Assistance

Day 5 - Pressing Template session 2

Day 6 - Bodybuilding assistance (upperback/delts)

Day 7 - Off

Any more questions fire away.

Cheers,

Marc

I thought of something similar as the best option, but sadly as a father of two kids (3years and a 4 months) training 5 times a week isnt an option at the moment. Iam coming of a two two days a week split I ran since the birth of my second son. I've been doing two full body days alternating heavy/light squats and bench and deadlifting once per week, rowing heavy the other day and finishing with some bodyweight high rep stuff (pullups, dips, pushups, upper back and core).

I will attend a local meet at the upcoming weekend just to support my guys and know where Iam at training wise/numbers. Iam planning to train 3 days after that since I feel this is the least amount of time I have to spend to see some progress. Would you go

Day 1 - Bench 1/Back assistance

Day 2 - off

Day 3 - off

Day 4 - Bench 2/Back assistance

Day 5 - off

Day 6 - Squats/light Deadlifts (seem to get very much out of 1-2 sets lighter/higher rep sets)

Day 7 - off

...or would you tell me to think about another template alltogether?

Squat and bench session 1

Off

Deadlift and back

Off

Bench session 2 and some bodybuilding

Off

Off

Depends on how you want to spread your training. For me personally if I was looking to only train deadlift of squat 1x per week I would make sure they were separate sessions so I had at least 2x lower sessions in the week.

Cheers

Marc

It is a 4 set workout although all sets should be near failure so it should offer more than suffice stress to podcue a strength adaptation.

Any more questions please shoot away.

Cheers

Marc

Thank you for your support!

Mario can you be specific to which programme you are refering too? The key elements of the linear programme have a calculator and the assistance should just be used to stick in the rep zones. i.e. if the programme says 2 sets of 8-12 reps then you should use a weight that is heavy enough you can't do it for more than 12 reps or that is light enough you can do it for at least 8-9. As soon as you can do it for more than 12 reps you should increase the load.

If it is for the template, there is no calculator necessary you just need to get the right ball-park weights

70-78%

87.5-95%

50-60%

For the sets and then use the rules provided to progress from week to week.

Cheers,

Marc

In the first program, is there a 6th week that is an off week? Or is the plan to start another 5 week cycle?

In the second program, is there any attempt to cycle the weight (intensity) on the heavy set from week to week? Or is it truly linear, where the plan is to have the weight (intensity) progress only higher?

Also is there a planned off/deload week in the second program?

Thanks for your time.

Thanks

First of all thanks for the high praise it is much appreciated!

And you are indeed correct strict press is just a standing shoulder press with not body english or leg drive.

The ed coan cycle should be a bitch to complete all the sets x reps on if you start with the correct cycle so the overload/progression comes through the programme.

I would add 2.5 kg to upperbody weights and 5kg to lower body weight cycle to cycle.

Alternatively you could start with a lighter max and rep out on 3x6 and 3x3 week to get some overload that way.

If you start with your true max however trust me you won't need to rep out!

Cheers,

Marc

I've been running the cast iron pressing template for a few weeks so far and am enjoying it. Would you recommend the 5 week linear programme though over the cast iron pressing template for when I start peaking for a meet?

In reference to training the bench press under the same conditions as a meet, would the pause be on every rep in the set, or just the first one?

Thanks

You can do either, for me I will pause about 60-80% of all reps 2-8 weeks away from a meet and 100% 0-2 weeks out.

I normally would programme it in as pause bench press just to prep for a meet.

In out of meet prep I tend to bench touch and go with very little arch so my strength gain on the bench is very transferable.

Cheers,

Marc

4days/week schedule. I like that it focus more on heavy lift and more volume than 5/3/1.

Can I stick with the Squat/Bench/Dead/Shoulder Press like in 5/3/1? I saw in the template that it incorporate 2 times squatting in the week and 2 time bench press (the second one is a variation).

Should I incorporate 2 bench session a week or the shoulder press count as a variation?

Thanks.

I would use the template for

Session 1 - Bench Press + Incline Bench (3x5 or 3x8 @ RPE 8)

Session 2 - Strict Press + Close Grip Bench Press (3x5 or 3x8 @ RPE 8)

Try and add weight to the secondary pressing exercises week to week and follow the pressing template above for the first exercise.

Nice article!

In the 2nd template can i make the two pressing workouts more even? Like switching the dumbell incline and bodybuilding(chest) on day 2 with dumbell shoulder press and bodybuilding(triceps) on day 2. So i get the chest work more evenly spread out through the week? Or will this yield me worse results?

Is there no planned deload? I should reset the weight for three weeks and then take one week off when I have stalled? Have i gotten it right?

Questions on cast iron pressing template, specifically this...

"Close Grip Press: Build up in fives to PB Attempt Set"

1) Is "Close Grip Press" the same thing as a strict overhead press, but with a more narrow grip?

2) What does "build up in fives to PB Attempt Set? Does this mean I should be doing singles, adding 5 lbs each set until I hit a new PB or attempt a new PB? Or does this mean I should be building up to a 5RM PB attempt?

Sorry if I overlooked the answer to this in the article or on other questions that were asked.

Can I do this with 2 squats and 2 deadlift? Can I do 3 big heavy?

What split can I use? Thank you

I would like to try the The Cast Iron Pressing Template — A Slightly More Refined Meathead Method.

Not sure what you mean by : Close Grip Press: Build up in fives to PB Attempt Set. Does this mean do sets of 5 reps working up to a 5rep pb? Like 60%x5, 70%x5, 80%x5, 90%x5, 100% /PB x5.

Also should I do the backwork with this that is in the Ed Coan template?