Setting a five-pound personal record (PR) serves so many purposes for both the competitive and non-competitive powerlifter. It's a symbol of success or achievement. It is validation or affirmation that your program is working, and the PR is your new benchmark from which all prior lifts now fall. But it's also where new lifters and some not so new lifters also get tripped up.

A little while back, I was fortunate to get an opportunity to interview Ed Coan. Yeah, that Ed Coan, seven-time USPF National Champion, six-time IPF World Champion and the guy who pulled 901 pounds at 220 pounds with his only gear a belt and a worn out yellow singlet. When asking Ed about PRs and training following the meet, this is what he told me: “The problem I see with guys today is [that] they don’t lay down a new base every time. After every meet, I went back, did my reps and worked on my weak points every single time.”

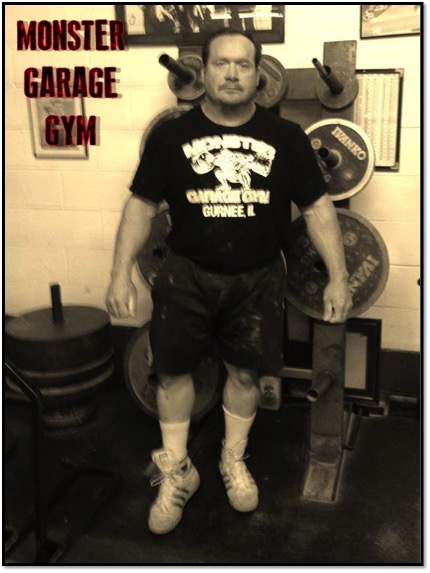

Photo by MGG: Ed “the King” Coan. Ed wasn't just a dominating powerlifter but a dominating powerlifter in multiple weight classes for over 20 years. After each meet, Ed rebuilt his base and worked on what he felt were his weak points. He is, arguably, the greatest powerlifter of all time.

The PR is all the things mentioned above, but it's also an indicator to regroup, refocus and go back to work. It's an indicator that you need to go back to the basics that got you to the PR. Go back to building additional strength so that your new PR is no longer the most you can squat, bench or deadlift but a number you can dominate on any given workout.

Be cautious. As powerlifters and number chasers, we can get wrapped up in the PR and then the story goes like this: “Dude, I just went 505 pounds on my squat. Now on to crushing 600 pounds!!” Or the lifter hears: “Just a five-pound PR. That’s not much of a PR.”

Let’s sprinkle a little perspective on this 505-pound PR squat and both of those statements. This lifter’s PR was 500 pounds. For his entire lifting career, this is the most that he has ever lifted. Ever. In other words, this is the strongest that this lifter has ever been in his lifting career, so the perspective isn't just a five-pound PR but rather taking the biggest weight that he's ever been able to successfully lift and adding an additional five pounds to it. Ratchet this up to a legit 1,000-pound squatter’s number to help illustrate the perspective involved. It isn't just five pounds but his all-time, bone crushing, "make one misstep and get stapled to the platform" 1,000-pound squat with another five pounds added to it.

My point is five pounds matters. Going back to the 500-pound lifter who set a new five-pound PR and is now looking at 600 pounds, he should go back to the training that got him there and, instead of an all-out effort to get that 505-pound squat, his goal is to now train to a point where that all-time max PR is now merely training weight.

The smarter money is on a training cycle that will take you to a 515- to 520-pound squat. Again, this isn't some measly little 10- to 15-pound PR for your squat. This is 10 to 15 pounds on top of the greatest amount of weight that you've ever squatted in your life.

The pursuit of PRs isn't some arbitrary destination but an ongoing journey through a lifting career, a journey that sometimes starts anew following an injury or some other setback. Further, the journey is never a race but a well planned, well executed series of training cycles built on the backs of fallen PRs. Ultimately, those fallen PRs are the bedrock foundation that future meet PRs are built on.

Photo: MGG Owner, Eric Maroscher and #4 ranked women’s RAW bencher at 181 pounds Kristin Johnson. Kristin has a 300-pound PR in the gym and a 275-pound meet PR. After every meet, she goes back to her bread and butter—reps, a long training cycle and a refocus on form, technique and rebuilding the base.

One of the reasons for dominating the meet PR is that unlike your gym PR, each and every meet is different. The warm-up time for your attempts isn't the leisurely pace that you train at. The warm-up room and meet platform aren't the same as your training settings. The bars are different, and there might be kilo plates. There are hundreds of variables involved. One meet not only differs from the training environment, but each meet differs from each meet. This is why it is key to dominate a PR in the gym first and then move on.

This whole mindset of breaking the PR and then working hard to dominate that PR goes hand in hand with the concept of ‘leaving a little on the plate.’ Just like eating too much at a restaurant turns the feeling of having a great meal into a bad stomachache and feeling like you're ill, it's better to zero in on your meet PR but not recklessly overshoot the number. By overshooting instead of hitting another five- to 15-pound all-time personal PR, you miss the third attempt by trying for the 50-pound PR and lose ground all the way back to your second attempt, and a sub-PR performance, in the process.

The bottom line is if the work—the consistent, well planned work—is religiously put in, injuries aside, the PRs will go up. So although it might take a number of meets to add up to a 50-pound PR, that will happen and there isn't anything wrong with chipping away at the stone that is your all-time PR.

Remember, it isn't just five more pounds. It's five more pounds on top of the greatest amount of weight you've ever lifted in your powerlifting career, so don’t diminish that nor rush future PRs in the process. Rather than have a lifting career full of meaningless gym PRs and a competition career strewn with PR attempts that failed, have instead a lifting career with a string of successful five- or 10-pound PRs, one right after another after another after another after another...

We all know lifters who “almost” this and “almost” that. Be the lifter who flat out white lights lifted the weight.