When I began this article series several months ago, I started with a question: do athletes with mental illness need to train differently than those without? As I read through different research and talked to various doctors, researchers, and lifters, I’m confident this is the case. But not only is this the case, I feel strongly that building a training program with a comprehensive stress management model in place will help any lifter perform better and have better mental health in daily life.

The first article of this series I discussed the prevalence of mental illness in strength athletes (and some of the potential reasons why), and in the second article I laid the foundation for a better understanding of stress and the links between training, mental health, and other stressors. With those first two articles in mind, now I will discuss how we can use that understanding of stress response to better design and manage training, recovery, and other variables that affect both performance and general well-being.

Often times when a lifter with mental illness is struggling (whether it be with work, training, social life, etc), the response is to either do nothing (the worst option but often the easiest to fall into), or to pick one method in an attempt to fix the problem. The issue with only choosing one method (whether it’s a counselor, doctor/medicine, supplementation, or training adjustment), is that you’re only addressing one component of a comprehensive system that mental illness, training, and all stressors affect. And because everyone responds to various treatments differently, if you put all your eggs in one basket, you’ll likely set yourself up for disappointment and frustration if it doesn’t work. I see this a lot with lifters who will finally work up the courage to see a counselor or doctor after years of struggles, and because they have a bad experience (whether it’s because their personality didn’t click with the counselor or because a certain medication didn’t work), they get frustrated and give up on the entire process. I’ve been there.

PART 1: Mental Health and the Strength Athlete: Strength Beyond the Barbell

This is why approaching changes with a more comprehensive mindset is more effective. It not only includes all the variables that affect your performance goals and health, but helps prevent frustration if one singular change doesn’t work. Training and addressing mental illness are similar in the fact that they both are a journey that takes time and typically a lot of trial and error to find your optimal approach.

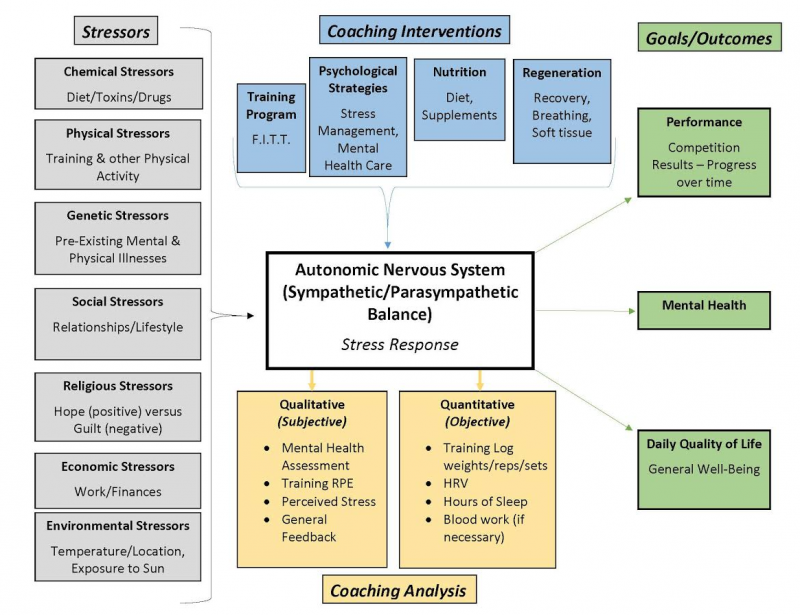

A visual example of a comprehensive approach like this is the coaching model I’ve been developing to work with my own clients, and to hopefully do some published research that will help mental health counselors in the care of their patients. Below is an abbreviated example of the coaching model, which will help you start to put the rest of this article in perspective:

As you can see, the stress response (like we discussed in my previous article) is the core of this philosophy. All the individual stressors, treatments, analysis, and results are all parts of the bigger picture. Utilizing a comprehensive approach that centers around the nervous system versus focusing on a singular approach is ideal because then you’re making those individuals approach (or “tools”) work for you, instead of being enslaved to one approach. Buddy Morris, Head Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Arizona Cardinals, has always emphasized how important this comprehensive approach is when managing stress in his athletes:

“The human body is nothing more than an interdependent matrix system that communicates with and amongst itself all day long through electronically charged molecules. You are an ever evolving and fluctuating organism that is self-regulating and supercompensating — you are nothing more than a bio-electrical field that is hell bent on one function: SURVIVAL! [homeostasis]”1

Every single thing that happens throughout the day, whether it’s a heavy training session, fight with your significant other, being outside in cold weather, or taking your medication, it all affects homeostasis and has to be accounted for when analyzing your training and mental health approach. Charlie Francis, legendary Olympic Track and Field Coach and a specialist on physical preparation, constantly re-iterated this in management of his high-level athletes. In his book The Charlie Francis Training System, it is emphasized that, “as a coach evolves through learning and practice, he/she realizes that the separateness of training factors is in fact an illusion, and with this realization the elevation of coaching to an art begins.”2

With this big picture approach in mind, there are four important components of this that you can begin to utilize right away to increase both your performance and your mental well-being:

- Create an Honest and Comprehensive Inventory of Stressors

- Utilize a Multi-Dimensional Approach to Stress Management

- Make Smart Programming Adjustments

- Take Advantage of Accountability and Support Systems

In depth analysis and interventions for each of these areas can be done (which is my goal moving forward with my coaching approach), but for the purposes of this article, I’ll briefly go into each and give you some immediate things you can do yourself.

Create an Honest and Comprehensive Inventory of Stressors

In my previous article, I discussed stress and how different stressors affect the nervous system (make sure to read that article if you haven’t already, so that this all makes sense), and Dr. Eric Serrano and I discussed how these stressors can be even further broken down into the following categories3:

- Chemical Stress

- Physical Stress

- Genetic Stress

- Social Stress

- Religious Stress

- Economic Stress

- Environmental Stress

Some of the above categories may be things you’ve considered before, while others may not be something you’ve thought of as “stress” before. Remember, like we discussed previously, stress is anything that throws off homeostasis. Any of the stress that fits into the above categories can be positive or negative.

As simple as it may sound, just sitting down and creating an honest inventory of all the stressors in your life will likely be pretty eye opening, and may provide you with some immediate changes you can make to improve your stress response. For instance, as a whole, you may think “I don’t really have that much stress,” but after creating a list from the above categories you realize you actually have a lot and might need to make some adjustments to your training. You also may see that these stressors are different levels depending on the time of year, and it may influence your training approach or even your competition schedule. In addition, specific stressors may provide immediate interventions that can improve your stress response. For instance, one environmental stressor may be that you live in a cloudy, cold climate and are rarely outside. This could be leading to low vitamin D levels, and supplementing vitamin D may improve your stress response, and in turn, your training and mental health (this is just one example).

Another important thing to do (which I work on with individuals who I discuss stress with), is to organize those stressors into controllable versus non-controllable stress. This activity not only can help further direct your approach to training and mental care, but also give you encouragement to see what truly is within your control and what isn’t. Another method that is helpful to do this is to utilize Stephen Covey’s Circle of Concern and Circle of Influence.4

Utilize a Multi-Dimensional Approach to Stress Management

This point is similar to what I mentioned in the beginning of this article about not just focusing on one method. Because mental health and training performance all ties into the same stress response system, you have to attack the problems from several different angles.

PART 2: Mental Health and the Strength Athlete: Why Powerlifters Get Ulcers

Unfortunately, one glaring weakness I’ve seen (and experienced myself) in the mental health field is that many professionals are only focused on one method of treatment. The best thing you can do for yourself is to find someone who can help build a comprehensive approach for you, or make sure to seek out various individual professionals for yourself. Why just meet with a doctor to discuss sleep medication when you can also see a Clinical Mental Health Counselor for stress management strategies, get blood work done to identify possible nutritive or hormone deficiencies, and perform restorative methods on your off days to reduce the stress load of training and improve your ability to adapt and get stronger? Improving mental health and training performance is a big puzzle, and you can’t expect to complete it without all the pieces to work with. Don’t be afraid to seek professionals for these components, and also don’t be afraid to find another professional if you aren’t comfortable with the first one you meet with.

Make Smart Programming Adjustments

Determining exactly which adjustments you’ll need to make to your programming will be decided through evaluation of the factors listed above, which is why I inventory these variables before putting a program together. For the sake of this article, if we look at someone who is a committed lifter, trains hard, and has a diagnosed mental illness, there are a few programming considerations I feel confident will benefit most people no matter who you are:

- Pick a program you believe in. In my previous article I discussed the influence that psychological state has on the stress response in the body (i.e., how you perceive a stress affects your level of response to it). The same goes for a training program. If you hate every second of training and don’t believe in what you’re doing, not only will it not work as well, but your negative responses to that training will be even worse.

- Pick a coach who understands the big picture. Not everyone needs a coach, but if you utilize one, find one who understands variables outside of just sets and reps for training. In all honesty, if I was just going to send someone a sets and reps template without considering other factors or modifying the program as it goes on, I’d rather just recommend they buy 5/3/1 or 5thSet instead and start to figure things out on their own. If you can find someone who knows a thing or two about mental health struggles and can empathize with you (notice I said empathize, not just sympathize), it is a huge plus.

- Train optimally. For a long time my focus was always on trying maximally, thinking “what’s the most I can do”. As time goes on, I see more and more the value of training optimally, and making sure every single component of the training program fits into the big picture goal, rather than proving something on that given day. Everything you do in training has a reactionary effect, both in training on other days of that cycle as well as on your mental health. Train hard, but make sure your effort is strategic, and not fueled by short-sighted ego. Adjust the intensity and volume of your program to ensure that you have time to recover from high-CNS demand sessions before the next heavy session.

- Set attainable PRs. A discussion I have all the time with lifters and clients is about setting up a program so there are consistently attainable micro-goals and indicators throughout a training cycle. This not only prevents you from being 1-2 weeks out from a meet and feeling the need to reassure yourself your strength levels (because you know you’ve accomplished the smaller goals you needed to in order to reach your larger goal at the meet), but it also prevents the mental burnout that we see too often of someone missing a big lift and then being depressed the rest of the day and week. Rep and indicator lift PRs are your best friend.

- Get in shape. Over time more people have come to realize being an out-of-shape powerlifter isn’t as cool as we think it is. Not only that, but performance can really suffer the more your aerobic base drops throughout a training cycle. In addition to performance, your ability to handle stressors diminishes the worse of shape you’re in. And if that wasn’t reason enough to walk or push your Prowler once in a while, steady state submaximal cardio can actually improve your stress response and improve mental health.5

- Recover as hard as you train. For a long time on my days off I basically just tried to move around as little as possible and just rest. But doing light conditioning/GPP/recovery work on off days not only benefits your performance, but also provides extra stress relief. Other methods such as diaphragmatic breathing exercises, massage therapy, acupressure-type methods, and Epsom salt baths can not only benefit the body through direct physiological means, but also facilitate recovery through improved stress response. If you’re “resting”, but a nervous wreck the whole day, you aren’t really getting a break from stressors that day (if anything you may be even worse off than training). Find productive ways to recover that also help you relax and engage that parasympathetic portion of the nervous system.

Take Advantage of Accountability and Support Systems

Mental illness can be a tough thing to discuss, and just writing about my own experience was difficult. Most of my friends and family found out about my issues for the first time by reading my article. I’ve found that one of the best things that this experience has done for me, however, has been to bring me accountability (if I’m going to write about this stuff, I sure as hell better be putting effort into my own mental health), as well as a whole new support system of fellow lifters and colleagues.

If you’ve been struggling with mental illness and haven’t talked to anyone about it in depth, I really encourage you to reach out to someone, even if it’s just a friend or family member at first. Some people are more comfortable speaking to a counselor first versus people they know, so this is a great option as well. Whatever you choose, speaking to someone about things is a huge step in the right direction and I give you a ton of credit for doing so. If I hadn’t, I certainly wouldn’t be in the position I am today.

This article went into some tangible ways you can approach your own training and mental health, but it can certainly go far beyond what is written here. Like I’ve mentioned before, this is a long journey but we’re all in this together. If I can be of any help don’t hesitate to contact me via the Q&A or by my email at joeschillero@gmail.com.

Helpful Resources

- National Alliance on Mental Illness: https://www.nami.org/#

- Project 375: Mental Health Advocacy (co-founded by NFL Wide Receiver Brandon Marshall): http://project375.org/

- Strength Over Suicide (S.O.S) Facebook Page:https://www.facebook.com/Strength-Over-Suicide-SoS-1037148352973435/?fref=ts

- National Suicide Lifeline: http://www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

References

- Morris, B. (n.d.). Deload to Reload. Lecture.

- Francis, C., & Patterson, P. (1992). The Charlie Francis training system. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: TBLI Publications.

- Mental Health & Strength Training Interview with Dr. Eric Serrano [Telephone interview]. (2016, June 01).

- Circle of Concern and Circle of Influence. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://uthscsa.edu/gme/documents/Circles.pdf

- Kern, M. (2016). Exercise, Physical Activity, and Mental Health. Encyclopedia of Mental Health, 175-180. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-397045-9.00064-1

I'm not sure really where to start or how to finish what I want to say. So thank you for sharing your experience , you have been a big help to me.