Let’s face it—in a world where being mobile is defined by the ability to tie your shoes without running out of breath, I think our idea of what movement is has been lost in translation. It could be the old-school approach to things. It could be that we just have zero body awareness. But what’s more important to note is that most people don't work on mobility simply because they have very little understanding of what it means or how to go about making it a part of their regular training regimen.

Although this premise is a little saddening, I still have hope for our future generation of lifters. So I'll dedicate some time to explaining why the ability to move is so important not just for your lifting career but for overall longevity. This particular part of what will eventually be a series is focusing on the basics of your ball and socket joints, namely your hips. So time to roll out a mat and put down the sandwich for a few minutes while we go through some joint greasing.

Mobility Basics

What is mobility?

Mobility can be defined as being able to move freely. Literally translated, it means being capable of moving or changing quickly from one state or condition to the next. In relation to our body, this means being able to move freely throughout our joints, ligaments and muscles.

Ball and socket joints are synovial joints that allow freedom of rotation as well as back and forth movement in all planes. In an ideal situation, you would have little to no problem getting full range of motion in any direction throughout these joints. With this information, a truly mobile hip or shoulder should be able to achieve multiple ranges of motion with ease and without discomfort.

Keep in mind, mobility isn't the same thing as flexibility, but the two go hand in hand. Your level of flexibility may determine the degree in which you can move to a certain extent, but it doesn’t have as much affect on how you move. And how you move can save your ass a lot faster than simply how far you can move. Mobility is a combination of flexibility, strength and control. It's the amount of usable motion that a person has through a particular joint. In other words, sitting passively in a split isn't considered being mobile. Being able to smoothly transition from a split position to something else in a flowing manner? That's mobility.

You could be super flexible but still unable to move freely and fluidly. Taking that into consideration, if a joint is restricted due to a mobility issue, you can’t put a Band-Aid on it by trying to stretch the muscle. A restricted joint leads to tight ligaments, which leads to tight muscles. Superficial stretching will only go so far if the joint still isn't moving (because we all know you can’t stretch a joint). Stretching your delts won’t fix a shoulder mobility problem. You have the right idea, but you’re using the wrong tools.

OK, so I know I’m definitely immobile. What does this mean for my training?

If you apply pressure to a rubber band that has been stretched to its absolute limit, eventually it will snap. The most unfortunate preventable accidents in lifting or any other activity occur when a lack of mobility meets an unmanageable amount of force. If you constantly beat your body down without allowing it to recover or move the way it was meant to, eventually you develop tight ligaments that restrict movement and contribute to muscle and joint pain. Throw weight on your back and it’s adding insult to injury. The fact that you’re immobile contributes a lot to your potential for injury. A healthy level of mobility is absolutely crucial for ensuring proper form and preventing future accidents.

I thought all I needed to do was stretch my hip flexors?

Right, OK. But if I asked you if you knew what your hip flexors were, would you be able to give me a definite answer?

When asked, most people believe their hip flexors are just “that area” in front of your hip running down your quad. Hence, this is why the majority of people think they're stretching their “hip flexors” when they're in a stationary lunge.

This isn’t necessarily false, but it is very vague. Your hip flexors are actually made up of six different muscles, all of which require different approaches to stretching. These are your psoas major, iliacus (sometimes grouped with the psoas and referred to as the “iliopsoas”), rectus femoris, pectineus, tensor fasciae latae (TFL) and sartorius.

So you can see now why using a one trick approach to mobilizing your hips isn't necessarily ideal. Sure, you may gain some flexibility and motion in one plane, but in order to excel, you must acquire good movement in all of them.

So what can I do about my sticky hips?

Remember how I said that ball and socket joints allowed for full rotation as well as back and forth movement in all planes? The most important thing to remember when designing a hip mobility program is to ensure that you are mobilizing from every direction. That means you can’t just drop into a forward lunge and think that you're building satisfactory mobility and flexibility in the hips. That simply won’t cut it.

Hips specifically have three planes of motion:

- Sagittal plane: Flexion/extension

- Frontal plane: Abduction/adduction

- Transverse plane: External/internal rotation

A good mobility program will include movements that target all these planes. And on that note, mobility in the hips is made easier when there is less tightness in the supporting muscle groups, namely the glute medius/minimus, TFL and piriformis. The hamstrings and adductors should also be considered when working toward better hip mobility.

Most powerlifters (and your average gym rats) have built some extent of mobility within the sagittal plane but very little in the frontal or transverse. You have to think of what your weak areas are and then build a program focusing on bringing up those lagging areas.

So if powerlifters are mostly dominant in the sagittal plane anyway, is it really necessary to build extra mobility in other areas?

Think of it this way. You don’t have to do anything. But if you would like to be able to move freely in and outside of the gym, you will need to stop focusing on being such a minimalist. What would happen if you get thrown out of alignment? What happens if your body is forced to perform a movement in a different plane of motion than you're used to? You need to be well prepared for whatever life throws at you. The human body is designed for mobility. Take advantage of the fact that you have such a complex, wonderful machine to work with by honoring it with the gift of free movement.

But too much mobility is bad, right?

Yes and no. As always, “too much” is always subjective. What is too much for one person is perfect for another. It's important to always work within your own capabilities and have as much mobility as is comfortable for you as an individual. While I might think it’s comfortable to throw my leg over my head, someone else might tear something. You get the point.

I think what is more important to note is that it isn’t dangerous to be very mobile. What is dangerous is being very mobile while at the same time being unable to activate the proper supporting muscle groups to ensure safe execution of a loaded movement.

Oftentimes what happens is that someone will increase their flexibility and automatically assume that their increased range of motion equals a more efficient movement. They get sloppy, and compromise their tightness and stability, which leads to other kinds of injuries. In reality, if you have no idea how to activate your stabilizing muscle groups, you're simply exacerbating the problem by loading a loose ligament. In this case, it is equally important to make sure that your muscle groups are firing properly before adding any kind of additional load to the exercise. But that’s something we will cover at another time. Got it? Good.

So really quickly, let’s go over some basics of the different planes so we can get to the fun movements.

Understanding Planes of Movement

Sagittal plane: Your basic squat is considered to be in the sagittal plane because you go into flexion and extension through the movement. Lunges and running also fall into the sagittal plane category. Sagittal plane also includes forward and backward motions. Of course, you can alter the squat by turning the feet out, which adds some emphasis on the frontal plane (because your hips open and slightly abduct when the toes are turned out instead of straight ahead).

Here's a simple test to determine your mobility in the sagittal plane versus your frontal plane. Squat first with your toes out, knees tracking in line, and your hips open. Then attempt to squat with your feet forward and knees pointing straight ahead. Is there any pinching in your hips? How low can you go before falling over? This is also a great way to test your ankle flexibility and stability.

Frontal plane: When you move through the frontal plane, you are actually abducting away from the body or adducting toward it. This could include movements such as lateral hip raises or jumping jacks.

From a strength training perspective, think of the adduction/abduction machines at your local commercial gym. Both of these train the hips in the frontal plane.

Transverse plane: By far the most neglected plane of all, the transverse plane involves rotational movement. Picture any movement in which you are rotating through the hips. Tennis, golf, baseball and even boxing are all very transverse-focused because they require a lot of rotational mobility in the hips in order to generate enough force. Tight hips equals a bad swing. No bueno. Not to mention, it becomes extremely easy to strain muscles when moving through the transverse plane, especially if you're already tight and haven’t fully warmed up enough. Most movements done through this plane are fast and explosive, so it is crucial that your mobility is good throughout to ensure smooth movement and minimal wear and tear.

Training the transverse plane is best done through chopping, swinging and twisting movements. When you want to develop rotational power, you must also add resistance. A simple way to mobilize more through the transverse plane is to add rotational movement to your regular stretches.

Here’s a simple “twist” to an otherwise frontal plane movement. Twist your torso away from the outstretched leg and drop the quad toward the floor for a deeper stretch.

Suggested Starting Points

So now that we've covered what mobility is, how it helps our training and the areas we should be focusing on, let’s go over some different basic movements that can be done for all planes of motion so that you have all your bases covered when putting together a program for yourself.

Sagittal plane:

- Body weight squat

- Forward lunge

- Straight leg walks

- High knees

- Front leg swings

Frontal plane:

- Cossack squats

- Lateral leg swings

- Jumping jacks

Transverse plane:

- Rotating medicine ball tosses

- Wood choppers (cable or plate)

- Russian twists

- Dowel twists

Putting It All Together

Now that you have your fundamentals down, it's time to put it all together. We know that we can't simply static stretch and that we need to be able to combine movements in a free-flowing manner to get the joints moving properly. We know that it is important to build mobility in all planes of motion and that it needs to be done frequently to prevent any “re-sticking” of the joints. So what now?

My suggestion is to start slow. Pick two movements from each plane and perform these before every lower body workout and on every day off. Play around with your own mobility limits and see what kind of combinations you can create and how you can make each movement flow into the next smoothly.

Pre-training, your mobility routines should take no longer than 10 minutes but nothing less than five. I always like to begin by doing a small bout of cardio first to get my body warm before performing any kind of mobility or activation drills. Post-training is when I focus the most on my mobility drills because everything is very warm from my training and I don't have to worry about wearing myself out before my main movements. Mobility work can be very tiring, especially for those of you who are very tight. It's important to time things properly so that you're still getting the most out of your training.

On your days off, you should be doing a minimum of five minutes every morning. This sets the pace for the rest of your day and can help alleviate any tightness you may have from the previous day.

Here is an example of what a mobility drill should look like. It’s a simple flow consisting of a Cossack squat, forward lunge into TP twist, and a pigeon stretch. Any sequence of movements you choose to put together should flow in the same manner. Of course, work at your own pace.

Customizing Your Movements

Keep in mind that when performing any kind of drill, you need to work at your own pace and with your own level of mobility. For example, if you are unable to drop your leg completely behind you in a pigeon stretch, you can alter the movement by keeping your back leg bent. Or if you are going into a Cossack squat, only sink in as low as possible before you notice your heels starting to rise up. And of course, when transitioning from one movement to another, it is perfectly fine to use your hands to support the transition. You definitely do not want to come crashing down into any kind of a stretch! Mobility work should be gentle and feel natural.

Patience is key, and videos are an excellent tool for you to gauge progress and double check your form.

A Note on Posture

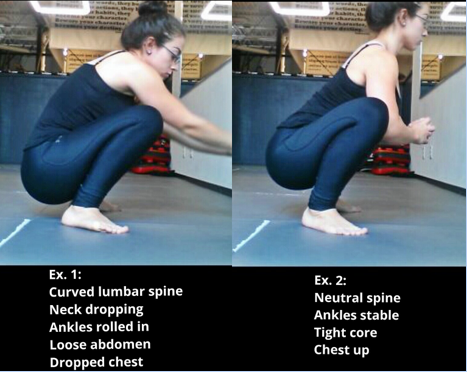

When practicing any kind of mobility work, you should always be sure to focus on your posture. It’s important to still maintain good form, as it will remind you not to get sloppy when you are practicing loaded movement. Here’s a simple example of some common form issues when getting into a deep bodyweight squat:

I hope this has helped some of you understand your hips a little bit better! Please stay tuned for follow ups to this article. I'll cover muscle activation and mobility in other areas of the body as well as advanced articles for the Gumby in all of us.

Christine's Training Log

By the way, you're body is flawless. You must work very hard to look like that!