Inspiring change for people with disabilities.

Based on my positively worthwhile 2016 experience at OCALICON, this year I returned to the nation’s premier autism disabilities conference in Columbus, Ohio to learn more. Serving the Greater Columbus area for eleven consecutive years, OCALICON is a face-to-face gathering of state and national leaders, educators, parents, service providers, self-advocates, scholars, and policymakers. Collectively, the event focuses on delving into common concerns and sharing proven solutions that address issues and challenges faced by individuals with autism, sensory disabilities, and low-incidence disabilities across their lifespan.

RELATED: Ocalicon 2016 — Nation’s Premier Autism and Disabilities Conference

With more than 50 presentations to attend within a 10-hour time frame (more to choose from compared to last year), here are the presentations from which I found great applicability to my work in both the private and college settings. Consider how these sharings apply to your previous, current, and future work aimed to assuredly impact children and young adults with autism.

I Am Potential: Overcoming Obstacles, Breaking Barriers, and Being and Doing More Than You Think You Can — Patrick Henry Hughes

Patrick Henry Hughes led the conference commencement sharing his remarkable life story of 29 years. Born without eyes and with limbs that couldn’t straighten, Patrick is a multi-instrumental musician, speaker, and author from Louisville, Kentucky. Accompanying him on the stage, as well as for every halftime show as a trumpet player for the Louisville Marching band, was his father, Patrick John. From birth, although it was difficult, Patrick John focused on his son’s potential. This unwavering mindset of love led to moving beyond obstacles and instead inviting ability to determine Patrick’s legacy. If you have a few minutes, watch ESPN’s coverage of the family. I can’t come even close to using words to describe the father and son relationship on stage you’ll witness in this video (above). It’s remarkable. And then Patrick played piano and sang for us. There wasn’t a dry eye in the auditorium.

Application: In 2009, I worked at Bethesda Children’s Home where I worked in the partial hospitalization program. Although the home catered mostly to children from Philadelphia for living and educational support, the partial hospitalization program provided for children from the neighboring towns of Meadville, Pennsylvania, specifically children who could no longer earn an education in the public school based on adverse behavior stemming from poor home life and multiple diagnoses.

Fresh out of graduate school and inexperienced in the field, surrounded by trays of medicine, padded rooms, and restraint support, I remember feeling scared and timid around these children. Some only seven years old walked around as tiny ticking time bombs, in a haze, angry, and troublesome. It was here I discovered really quickly that I couldn’t treat these children as their learned identity. I had to understand the diagnosis and treatment plan, yes, yet treat them as children, learn about their interests, and find potential. It’s then we were able to connect, and their shoulder chips got smaller and smaller. Children pick up on these things very quickly — if sensed as a disability they’ll fail you and themselves every time. If detected as somebody, they’ll rise to the occasion and beyond, every time. I use this approach for every child and young adult I presently work with.

Writing Matters! Building Written Expression Skills for Learners With ASD and ID — Robert Pennington

In Robert Pennington’s lecture, he presented the most current research on teaching writing to students with ASD and provided step-by-step descriptions of a few predictable teaching methods worth using to build writing skills: forward chaining, sentence structures, framing, and story writing. To put things into perspective, he reported 80% of children write at the basic level, with only 27% writing at proficient levels. How could this be when the root of writing demonstrates competence, shares a story, determines a listener, and therefore provides probable social interaction? He concurred this is what happens when academic procedures are sadly neglected as a result of attention being placed on disability and adverse behavior.

So what do we do? Based on his research, establishing the meaning of writing has to be at the forefront. Using sound methodology, do this by teaching word exchange for specific reinforcers. Examples include signing in and out, writing to a peer, Googling, playing games, and need-based requests (going to the bathroom, hunger, thirst, etc.). Once meaning surfaces through the habitual use of the written word and the methodology continues systematically with tweaks based on continual assessment, it’s then vocalization, expression, and social connection that improve. As you can guess, writing ability, overall, continues to improve as well.

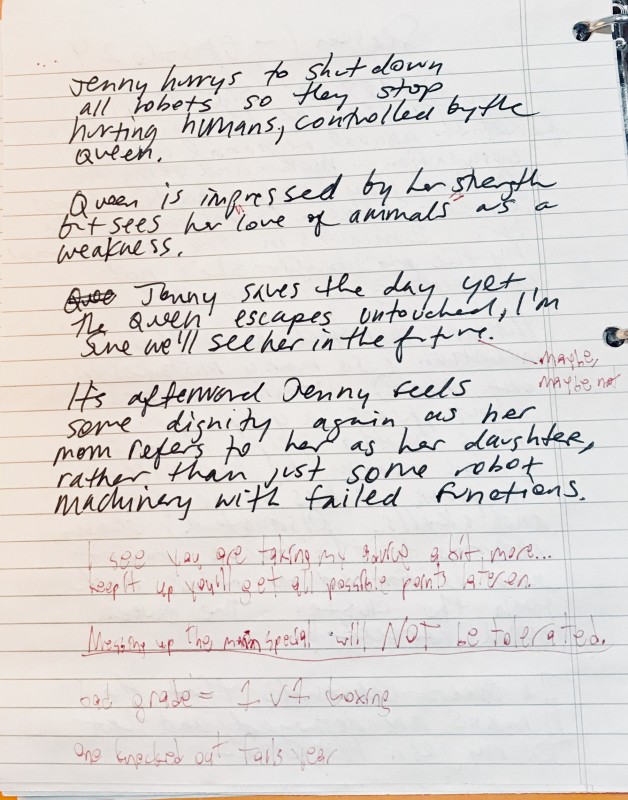

Application: Oh, the power of a note. I’m writing my first book on this very topic, showcasing how the written word started a lifelong fitness journey for one of my clients, Blaine Tate. Not only did it start our journey, but the use of the written word is also training motivation for Blaine weekly. It’s a point in our training session where he can express his interest for My Life as a Teenage Robot and assess my writing and attention-to-detail skills (edits in red ink are Blaine's in the image above). We then openly discuss the plot of the latest episode and the character’s motives with facts, opinions, and further expectations. Like Pennington pointed out, with the use of writing, Blaine immediately saw me as a listener, and so dialogue ensued.

As another example, I began to rely on the written word the first year facilitating Guy’s Aspirations, a social group intended for young male adults with autism to make friends and have fun. The program originally was void of voice. All I knew was what the former facilitator was interested in: food. When I asked the guys what they were interested in doing, they were silent. It’s once I passed out paper and pen and asked the same question that they began to write. What they wrote is what I prioritized and, in a year, rather than eating, we jumped, hiked, roller-skated, listened to music, bowled, explored a cave, and more. Now when I ask them what they’d like to do, they can’t speak fast enough. From this lecture, I realize using another means of communication was gold, but mainly because I read what was written on paper. Through the use of pen and paper, a newfound world has opened for them to explore and connect.

Using Social Scripts with Adolescents and Adults Significantly Impacted by Autism — Kathryn Doyle, Carla Schmidt, Kelly Garland

From the University of Cincinnati, the trio of presenters recognizes how ASD is a lifelong social communication disability where many of the interventions are intended for children. With only 25% of graduates leaving high school with social competence, you can see these skills are ill-maintained post-intervention. Changing the adult landscape for individuals with autism, Doyle, Schmidt, and Garland studied a script and script fading intervention using a multiple baseline design across three adults with significant ASD and comorbid ID. During baseline, the adults had minimal interaction with peers. When the script was introduced, peer initiation increased. As the script faded, scripted initiations were maintained across multiple settings, times, activities, and people. After reassessing two months post-intervention, the results maintained. Social scripts are a prompting strategy using phrases or visuals to initiate verbally in familiar and unfamiliar settings when it’s likely discussion is forced anyways.

Application: My main takeaway from this presentation was the need for prompting and to plan accordingly for every social event catered toward adolescents and adults with autism. I’ve been in many situations where I thought the location or activity would naturally spark conversation or play yet nothing sparked naturally without prompting. If a plan is in place, the chance to maximize connectivity and engagement with less idling is probable. Those are great odds! Realize, there are times I’ve come prepared with a prompting strategy and the group connects naturally without any interference. It's at a moment like this to let the conversation run its course until it begins to dwindle and then step in when appropriate. An example where I heavily relied on a prompting strategy to elicit interaction was this past summer while hiking with Guy’s Aspirations. Based on the long RSVP list, a gut feeling of mine led to bringing two shoeboxes and two markers.

My idea was this: ask for two team leaders, team leaders pick hiking teams, teams brainstorm objects to search for and collect while hiking, and hike together while searching for objects with unique specifications. The outcome was this: Two guys couldn’t raise their hands quick enough to be team leaders. Team leaders chose team players and created team names. Together each team devised what to search for while on their hike — they created rules along the way (team members needed to learn each other’s names and team members must stay and work together to help one another). Mind you, this was all possible with the aid of two shoeboxes and two markers. As you can see, a little prompting goes a long way, and I promise you this would not have been the outcome otherwise.

The Emotional Classroom: The Importance of Teaching Kids to Manage Their Emotions — Lori Jackson, Steve Peck

Although Emotional Regulation is not a criterion in DSM-V for a diagnosis of autism, ADHD, or other behavioral disorders, behavioral issues are reported most for these populations. Exploring Emotional Regulation in and outside of the classroom, Jackson and Peck shared strategies to develop emotional regulation in the classroom and enable students to build new neural pathways to create lasting behavior change.

Imagine a crying child running under a table. The question at hand is, "What emotion is driving the child's behavior?" Why is he crying and running under the table? According to Jackson, it’s then imperative for the child and teacher to identify the emotion ("I feel sad") and then back up and question what happened to make the child sad.

Although running under a table is not typically life-endangering to the child or others, there are many instances where the behaviors are destructive — sadness could trigger self-injurious behavior. In Jackson’s example, we know the child is sad, and that’s why he ran under the table while crying. Beyond six years old, this behavior is inappropriate.

Through cognitive behavioral therapy, the child can identify feelings and choose a healthy replacement behavior to regulate emotions instead. Mindfulness training, brain dumping, and creating an emotional calendar are just a few exercises the child can use to identify emotions that drive behavior and begin developing replacement behavior.

Application: For the longest time, Blaine fixated on the fact that one side of his body was stronger than the other. Training the body bilaterally, he was quick to train the right side of his body and prematurely quit reps for the left. Running away from weakness, this usually followed with a self-defeating statement (emotion) and a clever way to move on to another activity (behavior). Using emotional regulation in the gym, one day Blaine began to sulk during single-leg curls. He was able to verbalize that he was only going to train his dominant leg because the other was weak. Redirecting his behavior, I reminded him of his 200-pound rickshaw carry goal and how reaching this goal was dependent on strength from both legs. I added, “We’re lucky we can see weakness. It's like being handed a treasure map, moving us closer to our prized possession (in his case, reaching his 200-pound rickshaw carry goal)." This redirection was enough for Blaine. He now trains both sides of his body with equal intensity without hesitation or question.

Thank you, Traci and Dave Tate, for the opportunity of providing ongoing education to fuel this column, Blaine’s training, and my programming efforts with OSU. I look forward to attending Ocalicon 2018!