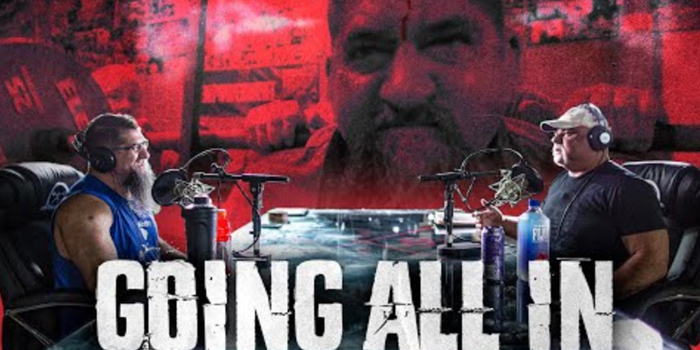

Clint Darden means no disrespect to any of the Masters-level World’s Strongest Man competitors, but he firmly believes he’s committed himself more and trained harder and smarter more than anyone else over the past two years. He can’t imagine half-assing training at any point in his life, especially not now.

“I think everyone owes it to themselves to live 100 percent the life of whatever sport you want to do. If you want to be a strongman or powerlifter, at some point in your life, you need to drop everything, and I mean everything. You need to drop your job. If you’re a young guy, sacrifice relationships and sacrifice having a family. Sacrifice money.”

Once someone attempts all of these things, they’ll know if this sport at this level of dedication is for them or not. Then, they can walk away. He suggests giving yourself two years to figure it out.

Dave Tate disagrees with Clint’s view here, as he sees more people doing strength sports as more of a hobby than a serious measurement of testing limits of the human body. Still, he acknowledges he’s a hypocrite because he put powerlifting first, and that’s one of the things he regrets looking back, particularly in regards to his wife and kids. A strength sport can be one of the top priorities, but don’t do it at the expense of things that are also very important in your life — those things and people might be able to help you in the long run.

One of Clint’s training partners is a 30-year-old in the prime of his life — he has the injuries of a 22-year-old, so basically nothing — a fresh, open mindset and outlook. On top of that, he’s six-foot-six and currently weighs 441. When Clint first met his training partner, he weighed 265 pounds. It took this guy a year and a half to put on that weight — drug-free, mind you. He can do it all: running, jumping, and lifting.

“I’m looking at him and I’m like, ‘You’ve got to go. You’ve got to get everything. You’ve got to go all in. You need to sacrifice. You’ve got so much talent that it’s a waste if you don’t give it everything. You’re not in a marriage; you don’t have kids. Financially, you’re OK. You know you’re never going to be rich, but you’re OK. I’m going to be really disappointed if you don’t give it everything.’”

Other than that inspirational speech, Clint has also told his training partner to make sure he always has one person you can tell everything to, and that this person will call you out when you’ve gone too far — the kind of person Dave refers to as an enabler — someone that’s OK with all of the stupid stuff you’ll do; the person who’ll call 911 if you go down with a serious injury and knows everything and can relay that information to the dispatcher.

Clint makes a distinction between Dave’s enabler and the person you’d tell everything to: his training partner will message him questions such as “What would you do?” but then go back and restate the question: “Well, not what you would do, but what do you think I should do?” What Clint does in a situation might be something his training partner would consider “psycho.”

“I think if you see someone with talent, I think you’re doing them an injustice if you don’t tell them to give it everything they have.”