It’s taken me almost four years of writing for elitefts to even put a shred of a spreadsheet in an article because, in my world, they don’t do justice to the layers of what it might require to get someone where they need to be. On the other hand, there’s a time and place, and oftentimes programming through injury doesn’t need to be nearly as complicated as we make it. I don’t know why, but it’s like we forget the very same basic principles that apply to normal training.

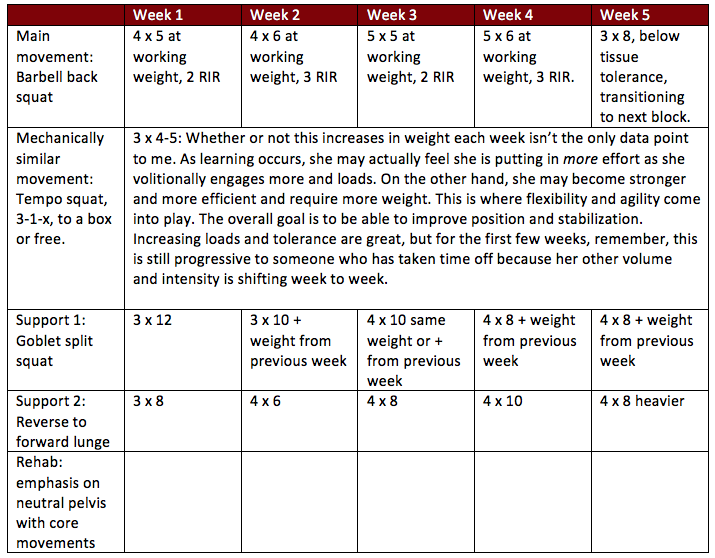

Here’s a very basic template of someone I worked with recently:

Here’s what I want you to notice: Nothing there is all that different from a regular training block for a movement. There are some more details that come into client history, how and why, movement selection, and specific instruction, but the basics of getting you back under a bar don’t have to be complicated. In the context of a good, better, or best solution, following basic principles with a targeted application is a really good solution. Most lifters know the basics of programming, and you can apply those same principles to create your own good solution.

Key components of a solid strength building program will consider intensity (relative and absolute), specificity, frequency, volume, tissue adaptation, movement selection based on strengths and weaknesses, emphasis on position, working strength-endurance when appropriate, and acknowledging the role of stability in strength building.

The variables need to be matched individually to the athlete based on recoverability, level of conditioning, training history, medical history, and athlete beliefs.

Ultimately, this culminates in progressive overload as a whole with an emphasis on targeted areas. This is very much what programming post-injury needs to look like. I’ve broken down how you can begin to think about these ideas below:

1. Identify injured tissue

This is case-dependent and may or may not be a necessary step. I’ve written pretty extensively that injury is tissue-dependent in terms of type and about how to treat or rehab them a little differently, but there’s also a difference between a true tissue injury (tear, rupture, tendinopathy) versus pain that is specific to certain lifts and even points within that lift, like low back pain in the bottom of a squat or deadlift. This may or may not be an important step for you — if it is, refer to my previous articles with the guidelines of muscle, ligament, or other soft tissue (think labrum) pathology to help you moving forward.

2. Identify the weak points

You know there’s a weak point, or minimax, in your competition lift, where you either lose bar speed or position. This might be where, in your strength programming, you add a mechanically similar movement to challenge the range or position in your main lift. With regards to injury and programming, most often what I see is a loss of position, consistently, just before this. Look at your position and how you are moving — not how you’re supposed to be moving.

In the context of programming to return from injury, a loss of position and change in mechanical stress lines based on levers with mechanical advantage or disadvantage changes demands on an area. This loss of position in the injury world has an analog of your strength minimax — this is ultimately what you’re trying to control. This is often why things hurt and part of what you need to address.

3. Delineate your current ability level

Get a little gritty here because the more detailed you can be, the more targeted you can ultimately be in your exercise selection and execution with programming. Maybe something like squats to a certain point feels fine, but a little extra volume there tears you up something fierce. Maybe a split squat or a change in load location (and thus stability demands) changes your ability.

RECENT: Don't Ignore Systemic Interplay

Elements to consider include:

- Load location

- Absolute intensity

- Relative intensity

- Range of motion, loaded and unloaded

- Overall volume tolerance (Can you tolerate 30 total reps at a weight in a given session?)

- Stability/endurance tolerance (Can you do 8 sets of 4, but not 4 sets of 8?)

- How sensitive is your threshold? (If you can do 6 reps without pain, does doing 8 make the situation a little worse or a lot worse?)

- What is the risk-reward for pushing the threshold? Are you flared up for a few hours or a few days?

You’ll want to identify at least one movement that you can do any day of the week and at least one that feels a little tenuous. These are your bookends that your training can operate between.

4. What body do you live in posturally? What demands do you have on it every day?

If you live hunched over at a computer, it can be hard to open up your chest and shoulders enough to get under a bar to squat and appropriately load what happens below the ribcage. How you spend the hours outside of training have a huge impact on how you come into training. You can think of this area as all the stuff you know you need to work on mobility and stability-wise.

5. What is your overall recovery like? Stress levels? What are your beliefs about pain, certain movements, and training as a whole?

There’s merit to understanding why and how you think the way you do about training. Some of what you tease out might actually require more mental agility than physical.

For example, if you believe, “I just suck at right leg single leg-work. I always have. It just hurts, and pain means I need to stop,” you’re left with a choice. You can stay within that framework or you can ask yourself more questions that may lead you to answers that dramatically change your training, and therefore, your results.

And until I know you, I can’t say if there’s a right or wrong response to that. The things you need to tease through in this step are, in my mind, the hardest and also the most important. How willing are you to have your thoughts challenged?

Here’s the background on the lifter whose general template I posted above and an application of the principles outlined:

Unilateral hip pain with confirmed bilateral labral tears. She’s a very strong lifter with a long training history and maturity, having pain with daily activities, like walking. Her previous physical therapist worked on hip/glute strength in the way you might expect from a physical therapy clinic that probably helped with coordination a bit, but not in the way she needed.

RELATED: The Mind-Body Link: Posture Yourself Into a Winning Position

Up to a certain point, she can squat a percentage of her max (and it’s heavy!) but will have pain especially coming out of the hole. She’s currently on a high volume program doing tens and eights with squatting and alternating heavy squat/deadlift weeks as she feels she can only recover from one heavy lower movement at a time. She also mentioned rarely actually feels her glutes working with her squat.

I mentioned the word integration earlier, and it’s because she has a lot of strength, but there’s likely a timing and pattern issue contributing to poor control. Improving proprioception of certain muscles is one tool that can help with integration, so we’re going to use it.

This lifter has a lot of physical therapy-esque exercises she’s done where she can proprioceptively feel certain muscles working, and we’re going to use them before her session with the intent of increasing a little blood flow and improving mind-muscle connection before loading.

It’s a small difference, but 10 percent better per session over the course of eight sessions adds up to something I really like.

Here’s how we went through all the steps listed above and wrote one block of programming:

- Injured tissue: Her labrum is bilaterally aggravated more with deep flexion, but also has hip pain with walking. With the hips, especially labral pathology, co-contraction of both large and small muscle groups tends to be one hugely effective route for feeling better. They need to be able to operate with both strength (maximal lifts) and endurance (more volume/time).

- Weak points: Consistently in the hole of her squat, there’s a notable change in pelvis position and utilization of low back to help get out. Glutes and core are strong but not integrating together well, creating what might be more instability in a very mobile joint. Her morphology looks like it’s not that there’s one good or bad pelvis position for her, but the change in position is what irritates the hips.

- Current ability level: She can squat most weights with good technique and positional control to a threshold of 5-6 reps. As she increases reps, her ability to maintain position deteriorates a bit with anything above 30% of her max. Between 30-70%, 6-ish reps look the same positionally with appropriate changes in bar speed. If she crosses the 70% barrier and increases reps, this is the most irritating situation. Her risk-reward is unfavorable in that she is then in pain for the remainder of the day. She can perform single-leg movements but doesn’t like them. A goblet position is easier for her than a unilaterally loaded position. Unilaterally loaded at her side is easier than a unilaterally loaded front rack. You can see some of the progression that can occur over the next few weeks based solely on current ability.

- Daily physical demands: This gal works a desk job and knows that when her upper back and shoulders get tight, she has a hard time feeling good under a bar. When she’s tight up top, she’s forced to shift position in the hole. She can have pain walking, so she knows this also isn’t an issue based purely on maximal strength but likely has a timing and/or coordination component as well.

- Recovery and stress management: Stress is high, and this particular lifter is also like a lot of us in that she holds tightly to her training. I feel for her in that one session going poorly can lead to feeling absolutely destroyed physically and deflated mentally. We spent a LOT of time teasing through the mental aspects of why, how to reframe, and her willingness to be agile with her training. I truly believe her best strength and indicator of success is personal awareness and introspection. It has set her up HUGE.

- Goals: She needs stability and control through increasing ranges of motion, so our programming needs to address that. She can handle relatively heavy weight and is prepping for a meet, so optimizing intensity and volume progressively can not only help her get stronger but should also address major needs her hip has.

On returning to the table above, there are a few things to note:

- Progressive overload emphasized, but not dogma.

- This lifter’s emphasis is on maintaining one pelvis position through the movement and stabilizing it. Her spine is one that even when she’s in a neutral ribcage position, it has a bit more extension than some people’s spines, so I’m less concerned about what exactly that looks like and more interested in her ability to control that position without pain. She does this in EVERY exercise for specificity.

- The goblet squat and lunges could be paused or maybe she could pause the last rep for increased stability demand under a little fatigue, and it may be one variable she modifies as she moves forward. While I’m generally a big fan of paused or tempo work, this gal also requires dynamic stability and endurance, so appropriate exposure in the form of the goblet squat or forward/reverse lunge is one way to start.

- These movements were chosen because one is her “I can do it any day of the week” while another has a higher threshold with regards to skill and demand.

- Her rehab work is actually done in her pre-training pump and emphasizes core/ab stability and glute/hamstring proprioception. Some people would rather do a little extra post-training, and that is fine and might be necessary if YOUR rehab work fatigues you. As with many things, it depends. This is where your overall current ability comes into play.

All the factors outlined in these steps ultimately come together to optimize sessions for you, and while there are ways to be VERY specific, there’s no one right or wrong way to program through this. If you’re covering your bases and addressing your particular needs, you can always modify.

If you wanted to get into the better options rather than good options, you’d start looking more at proprioceptive deficits, mobility, and control deficits (especially given the hip joint is so multi-planar mobile). If you wanted the best options, quite frankly, you’d hire someone who can break down layers like proprioception, position, tissue tolerance, and your particular morphology and psychological components for you. Programming through injury is just like every other realm of fitness in that it is complicated and it isn’t complicated. You need to decide what you’re looking for.

READ MORE: Are Bands a Bad Idea for Rotator Cuff Strengthening?

Bottom line: Your rehab doesn’t have to be endless amounts of time away from the bar, frustrating sessions where you aren’t sure if your pain is going to show up or not, or chasing your tail. You can be smart enough to program through it with a basic understanding because it really doesn’t look all that different from our regular form of programming. Be empowered to step back, look rationally, and plan using basic principles.

As always, you can reach me at dani@mergeperformancept.com with questions.