Rugby fans across the globe know that it is one of the apex sports amidst the realm of endeavors that demand resolve, tenacity, and resiliency from its competitors. There is no sport in the world, however, in which competitive results are built solely upon its participants’ robust psycho-behavioral qualities alone.

Like any other sport, there are specific technical performance factors that serve as the tradecraft for Rugby men and women. It is these actualizations of the hard won efforts spent on developing various technical, tactical, physical, and psychological qualities that serve as the difference makers during competition.

The imminent 2015 Rugby World Cup will serve as the proving grounds for the competitors to demonstrate these skills.

Some of what I encourage viewers and coaches alike to pay attention to are various aspects of technical skill that I spent time discussing with my friend and head coach Errol Brain when I served on staff with him and the Portuguese National Side during the 2012 campaign.

A degree of what I will discuss here is rooted in applied physics and mechanical principles that serve as the basal constituents of all movement.

Synchronization of Force Application During the Scrum

The scrum represents a uniquely coordinated summation of the locomotive potential of the forwards and the control of their bodies in space. The propulsive machinery of the forwards is only as good as the geometric position of their bodies and, ultimately, their synchronized application of force into the pitch.

- Pay close attention to the cohesion in which, particularly, the props and hooker maintain their alignment as the pack initiates motion into first contact. Subsequent is the footwork of all of the forwards during the scrum and the degree to which it is synchronized specifically in the attempt to gain ground

- The position of their backs: the back should be parallel to the pitch in order to optimize the ability to transfer force into the opposition and gain ground. If the shoulders rise the advantage goes to the opposition and if the shoulders drop the ruck collapses.

- The angles of their shins and the position of their knees in relation to their hips that is a result of the degree to which their hips are flexed. Or more simply, note the position of the player’s feet relative to the plum line descending from the crease in the hip. If the knees are too far forward the player mitigates his ability to generate forward locomotion because the ability to drive forward is vastly inhibited as the feet move in front of the hips. Alternatively, if the knees are too far behind the plum line of the hip the player diminishes his locomotive potential for a different reason- his hips and knees are too close to being extended to the point in which he cannot drive forward anymore without taking a step.

Scrum Drive Special Exercise

- May be performed in nearly any weight room, optimally on a power rack in which the support pins may be set so that the player’s back is parallel to the floor (this squat rack was all that was available so we made do with what we had)

- Note the starting angles and position of the feet relative to angle of the thigh

- Note the near complete, but not complete extension of the thrust. As in scrummaging the forwards must replace their feet very quickly subsequent to every thrust and the degree of extension is predicated upon whether dominance is achieved. For this reason, it is practical to have the forwards execute this drill a number of ways

Body Position During Ball Carrying into Contact, Forming the Ruck, and When Tackling the Ball Carrier

The optimization of a player’s body position, regardless of whether carrying the ball into contact or taking on a ball carrier, is to out leverage his opponent by achieving a lower center of gravity.

- Far too often in the sport we observe players attempting to get low by bending at the waist as opposed to bending their knees. In this way, lessons from proper ground gaining scrummaging may be taken and applied to carrying the ball into contact and tackling the ball carrier.

- If the ball carrier merely bends at the waste, minimally bending their knees, he greatly reduces his ability to both generate forward locomotion as well as prevent the opposing force from the tackler. Correspondingly, an offensive player forming the ruck in the same posture (only bent at the waist) contributes to a pitiful structural architecture that is much more easily overcome by defenders with intentions to blast the ruck.

- Lastly, the epidemic of tacklers being in an upright position while “receiving or catching”, as opposed to attacking, the ball carrier renders a situation in which the ball carrier is assured to gain ground after contact, no matter how slight. When one factors the ground gained by the ball carrier during every such contact an interesting tactical formula appears. More on this later…

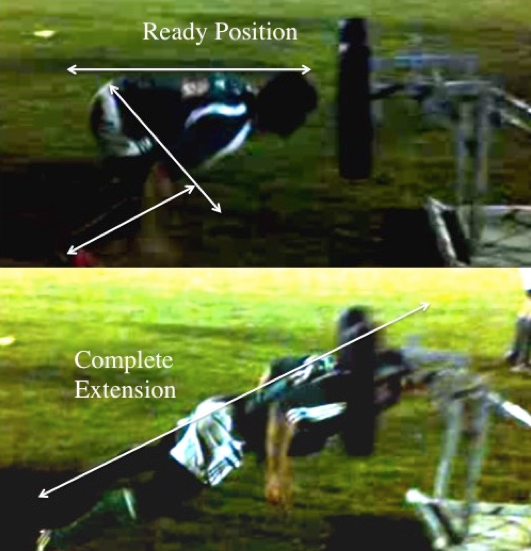

Drill to Reinforce and Automate Penetrative Posture

- In the ready position the player’s hips are low because of knee bend and his back is parallel to the pitch

- The penetrative effort is accomplished via the complete line of extension from shoulders to ankles

The Human Highlight Reel Richie Mccaw

- Here’s Mccaw penetrating the line for a try off the ruck

- The complete extension allows him to deliver maximum penetrative force through the tackler

Catching Contested High Balls and Pursuing Kick-Offs

Regardless if the receiver is acting alone or as part of a unit, being lifted, it is critical to demonstrate ownership (that ball is mine). In this way, particularly when contested by oncoming defenders, the receiver must be aggressive in assuring possession of the ball.

- Granted, the obvious nature of such a statement borders on patronizing, however, it is being stated because of repeated observations of receivers failing to own the ball.

- By association, when pursuing a kicked ball it must be the defenders objective to win possession as opposed to swatting at the ball to prevent the receiver from catching it.

- While we’re at it, chasing loose balls on the pitch demands utter commitment on behalf of those in pursuit. If the space isn’t available to scoop it and run with it the player must be aware enough to dive on it regardless of how many bodies are in close proximity. Take note of those players who lack a sense of urgency to pursue the loose ball or who hesitate and wait for someone else to make a play.

Attitude During Phase Play Attack

Waiting for something to happen is a recipe favored by the opposition- because they will make something happen to your detriment.

Take note of the sense, or lack, of urgency for offensive players to move quickly to either support the ruck (and the effort at which they do so) or re-assume their position in the line of attack after the breakdown.

- A sluggish approach into the ruck or a lackadaisical re-integration into the attack line are multiples that contribute to a sum total of opportunities lost.

Speed kills, and not just on a line break toward the try line.

- The speed at which players position themselves for tactical advantage in and out of the breakdown is every bit as important as their ability to out sprint their opponents in a foot race.

Readiness to receive a passed ball

- Every member of the attack must be ready, at any point, to receive a passed ball. There is absolutely no excuse for a turnover or knock on to occur as a result of an offensive player’s lack of readiness to receive the ball, watch it all the way with both eyes securely into his hands, and do so without regard of approaching defenders.

Defensive Organization in the Set Piece

Same as the price paid by offensive personnel who are lazily reforming the attack after the breakdown, defensive players who demonstrate idleness in the set piece leave unforced gaps in the line.

- This space equates to wide lanes for the offense to penetrate.

- Perimeter defenders slow to reform the line in set play create a situation in which they are easy for wingers to beat on the outside

- It must be the directive of defenders to rapidly re-acquire their designated position in the line after the breakdown.

- It’s one thing to possess the fitness and sprint speed to get from point A to point B and another thing to have the tenacity to do so every single time for 80+ minutes regardless of the score, pain, or fatigue.

Tackling

Returning to the point that was left off on regarding the ground gained by ball carriers during contact with tacklers who “catch” them in an upright position…

- Consider each of these scenarios and, provided the ball carrier is met by a single tackler, the mechanical advantage the ball carrier receives by maintaining a center of gravity beneath the upright tackler is one that often results in the ball carrier gaining an extra meter or two after contact.

From a tactical attack standpoint, if every ball carrier is utterly committed to out leveraging the tackler inside the 22-meter line, and gaining two meters beyond the mark of each break down, it will only take 11 attempts to cross the try line.

- For many locks, this distance merely represents one body length.

- Clearly the counter argument, provided the tackler remains upright, is how effective the ruck holds up and at what distance the player who receives the pass, quick ball or not, is from the line parallel to the ruck.

- As to the development of these, and other skills, in practice/preparatory efforts, there are concrete methods of skill development that are often void in the preparatory efforts of many teams.

As someone who has consulted with performance coaches for Aviva Premiership, Super Rugby (AUS), Guinness Pro12, Japanese Top League, and National Sides I have observed the many aspects of technical skill advancement that are rarely utilized at all levels of the sport.

While these points of interest only represent a handful of the much larger list of technical performance factors that contribute to the outcome of every contest, they are nonetheless vital for each team and player to optimize.

Globalsportconcepts.net

Athleteconsulting.net

Business contact: athleteconsulting@gmail.com