Block Periodization

A macrocycle refers to a block of training that is longer than a meso or micro cycle. A microcycle refers to a small periodized portion of training, usually a week, that comprises a mesocycle. A mesocycle is a slightly longer block, usually three to six weeks, that acts as a stepping stone for the adaptations you are seeking in your macrocycle. A macrocycle is your treasure map to reach a specific goal that can last anywhere from a few months to two or three years.

These terms refer to a type of programming known as block periodization. Block periodization was born in eastern Europe in the earliest years of sport performance and it propelled sport performance to new heights. This is a highly effective yet intricate method of programming that involves long term vision as well as deep insight into the participants. Of course individualization is a huge part of any program; however, block training has a very real brutality to it. No, not like Mountain Dog brutality, where you cant walk or feel your hands. This is a much slower, soul draining, mentally sapping brutality — the type of brutality that comes from monotony. A true master of a skill is a master of monotony as well. Skill mastery is a key contributed in the success of block periodization. As the athletes advance they become further submerged in their movement patterns and finish the programs more neurally sound than ever before. Block periodization is certainly not for everyone. There are three things you need to have in order before even thinking about using block training.

The first is a baseline level of strength. This is incredibly hard to quantify as a criteria, but if you are still able to progress from linear periodization then you most certainly do not fit the criteria. With the proper baseline level of strength, it is also assumed there is a baseline level of hypertrophy. The participant should not be a beginner and should be able to handle loads over his/her bodyweight. This is not to scare anyone away from block periodization, but I firmly believe in getting the most out of the least. If someone is enough of a novice to make consistent adaptations using low level programming then why expose them to something complicated? Let them adapt until the adaptive process slows, and then progress them. This is a way to ensure long term development as well as preventing overuse injuries.

The next thing you need in order to make block periodization work for you is sport specific skill. This is also difficult to quantify. As a coach, we have few objective measures to quantify sport specific skill; much of it relies on the coaches eyes. A certain level of proficient sport specific skill should be developed before embarking on the program. This is partly because of the type of progression scheme used in block periodization, that I will discuss in further detail later. It is also because block periodization emphasizes peaking. If the sport specific skills are not concrete, they will begin to falter early in the program, rendering your peak inefficient.

RELATED: Cutting Weight for Strongman: Is It Helping or Hurting You?

Finally, time is the most important factor you need to utilize block periodization to the fullest. The participant will spend anywhere from four to eight weeks, maybe more, in each block as they transgress through the program. Macrocycles can last up to a year depending on the frequency of competition and the participants goals.

These three prerequisites must be met before considering if block periodization is right for you. The next step is to objectively analyze yourself. This type of periodization gives you the same repeated stimulus over and over for weeks on end. This is not the type of program where you deload every four weeks. It has minimal variance day to day. When participating in a program that is so demanding, recovery and stress management are imperative. If you work a very high stress job, have unstable nutrition, do not hold training as a major priority, or are mentally weak, block periodization may not be for you. To give a comparison, a common block style program is Smolov, which many of you are familiar with. Not all block periodization is like Smolov style programming, but they are part of the same family and share many characteristics.

The Sport of Strongman

Strongman is a unique sport. Every competition is different, there are a seemingly infinite amount of events, and you are unsure of the events until eight to ten weeks before the competition. The events are up to the promoter and the odds that you will ever do the same events twice are slim to none. The feats in strongman are nothing short of spectacular. We have seen over 500 pounds placed overhead, over 1000 pounds deadlifted, and over 500-pound stones be lifted to platforms — all while including moving events to test the athletes speed and athleticism.

The history of the sport can be traced back to the 19th century. Famous events like the Thomas Inch Dumbbell, the Cyr Dumbbell, and the Apollon’s Axle are some of the oldest and most famous events that are still used today. Some of the original strongmen were circus performers who displayed acts of strength including those that are no longer used today, such as the bent press.

Even today, the sport is alive and growing. There are high level competitions around the world year-round and we are seeing the sport pushed to new heights yearly. Although the variety of visually impressing events is what brings people to the sport, the community is what makes people fall in love. There is an incredibly supportive community around the sport that pushes the competitors to constantly progress. It is not uncommon to see competitors training together or to see your competitor cheering you on. Due to the uniqueness of the sport, it may be difficult to train events at your local gym. However, social media makes it easier than ever to find a strongman group to train with.

Competing in a sport where you never know the events ahead of time can be difficult. However there is a general template that fits almost all competitions. In 90% of competitions there will be five events, the other 10% include top tier shows that may have 6-7 spread over the course of two days. The top tier shows are less conventional but still follow the typical template. There will always be some type of press, moving event, hip dominant lift, and loading event. As you may have noticed, that is only four categories of events, leaving one open spot. Most commonly you’ll see two moving events, but it is not unheard of to have two pressing events or two loading events. There will almost never be two hip dominant movements.

In competitions, the rules are often up to the promoter, so be sure to read the entry form thoroughly. A major rule that applies to all repetition-based events is lockout and down command. Any event where reps are counted there will be a down command. The battle for the down command starts when the athlete shows control over the implement and all appendages involved in the movement are locked out. Once locked out and demonstrating control, the judge will give you the down command. This gives you official credit for the rep. It is incredibly effective to make eye contact with the judge right away, stare deep into their souls, and try to make them a bit uncomfortable. You’ll get the down command faster.

As far as moving events go, the rules waver based on the event and promoter. The most important rules to be aware of are sliding penalties and crossing the finish line. Slide penalties are when the implement is dropped and slides for several feet meaning the athlete has less distance to ultimately cover. This results in a two-second addition to your time and can really hurt your score if you are trying to be competitive. Some events only require the front of the implement to cross the finish line, some the back. However, always take the implement clearly past the line regardless of the rule. Do not leave it up to the judge's discretion if you crossed or not. This is the worst time to suffer a slide penalty, or worse, they make you go back and try to finish. This is worst case scenario: you think you are done and walk away, just to find out you have to get back under that 700 yoke to budge it four inches. Meanwhile the clock is still running.

Loading and odd object carrying events have a blend of the rules listed above depending on the type of event, which is again, up to the promoter. When completing a medley or loading to a platform, the most important rule is to get your hands off the implement and leave it in a stable condition to stop the clock. Making sure the implement is in stable condition is the most important. It's better to spend half a second making sure it's not going to fall over than to rush to get your hands off and have to redo the rep or stand it up. Strongman is about clean and efficient movements, not rushed and haphazard mistakes.

WATCH: Clint Darden

Coaches How to Shave Seconds Off the Farmer's Walk

Pressing is one of the most iconic strongman events, with good reason: it's awesome. It is incredibly uncommon to have anything “normal” pressed overhead. The most common implements are log, circus dumbbell, axle, keg and (the less common) block press. Any of these implements can be thrown into a medley together. Medleys have variety within themselves as well. They can be completed for time, the last implement can be for max reps, and I have even seen medleys being completed for multiple rounds. If you are not pressing in a medley, there are three main variations: clean once and press away, clean and press each rep, and my personal favorite, the max clean and press. This offers plenty of variation, so you can imagine how difficult it can be to master them all.

Hip dominant events are guaranteed to be in every single show. They can include: deadlift off the floor, deadlift from 12 inches, deadlift from 18 inches, Hummer tire deadlift, max reps, medley, axle bar deadlift, car deadlift, wheelbarrow deadlift, tire flip, squat lift, and keg toss. The medley will typically contain multiple implements to deadlift. Deadlifts are most common and can be varied in dozens of different ways each with their own unique twist. Using an axle bar to deadlift is much different than using a standard barbell; car deadlift is completely different than wheelbarrow deadlift. Hip dominant events tend to be either the competitor's wheelhouse or Achille's heel.

Moving events may be the most variable event in the sport. There can be an infinite amount of potential events, spanning from 50-60 feet straightaways to medleys where you cover over 150 feet and every where in between. Moving events have the unique variant known as the carry and load. I group this with moving events because it is much more movement-based than loading-based. The athlete typically must carry two to four implements and load them over a bar or to a platform. These are exciting events and the implements are usually a keg, stone, or sandbag. However, it is not unheard of to have something like an I-beam in a medley. Any moving events can involve unconventional implements like duck walk, Conan’s wheel, hussafel stone, anchor/chain drag, zercher carry, frame carry, odd object, natural stone, yoke, farmers, and many more.

Finally, the loading events. These are the events on ESPN that got strongman its image; “the fat guys who lift giant rocks.” Although stones are the most common loading event, there are plenty of others. Stones can be varied into a few different events: stone carry and load, stone over bar, max stone (for weight or height), stone series, and stone to shoulder. It is not uncommon to have keg over bar or keg carry and load or a sandbag model of either. These events are all characterized by picking an object off the ground and loading it via triple extension.

The Strongman Training Perspective

The reason I went through and defined every type of event and its potential variables is to allow you to more fully understand how to look at strongman training. With the sheer amount of potential events alone, it would take well over a month of just training events to hit each one just once. Furthermore, if you're in the sport, you know how much just a few sets of intense event training can take out of you. So what are you to do? One approach could be to cycle through popular events: log, axle or DB press; yoke, farmers or some type of anterior carry; deadlift; and stones. The issue you then run into is cycling through events or dedicating your entire training week to events. What about not hitting events until a contest, then focusing on those events? That is a better method to follow but again, how do you properly prepare for the contest?

Despite common belief you do not need 12 weeks to prepare for a show. Depending on experience and how many events there are 6-8 weeks is a perfect amount of time to get your skills sharpened. What are you to do with the rest of your time? What about getting your events better throughout the year? Honestly there isn’t any one correct answer. That is how science works. In research, you cannot necessarily prove your work correct; you can only disprove. The final theory that has stood the test of time then becomes law, which still doesn’t make it “correct,” just harder to disprove than others. There are exceptions to laws and every now and then we see laws get debunked. The same can apply to programming. There are a million ways to peak and athlete for a contest and many will be successful. You must carefully record and pay attention to training over time to find what does not work. Stick to what does work, but be open minded to other possibilities that may work better.

The first step in devising a long term plan for your strongman success is to objectively assess yourself. What are your goals in the sport? What is your training age/history? What is your realistic level of commitment? What are your weaknesses/strengths in the sport? These are just few of the very important questions to ask yourself. The amount of times you compete in a year should be determined by skill level and goals. If your goal is to just participate and enjoy the sport versus trying to be the best in the world, your approach to competing will obviously differ. If you are a novice, I recommend you compete in more local competitions with less specific preparation. Conversely, I recommend the more advanced competitor participate in one to two local shows to get qualifications if needed and put their focus on preparing for one to two big stage shows a year.

Mike Mastell gives great perspective on when to cut weight and how to prioritize what class to compete in.

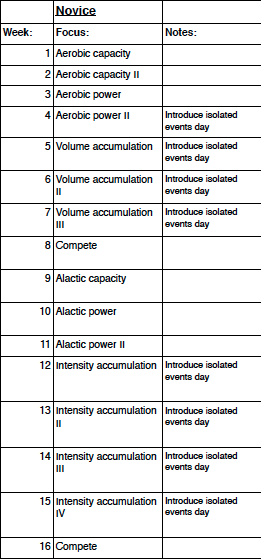

The Novice Macrocycle

As an extremist, I competed 14 times in my sophomore year of college. The competition binge started just weeks after my first novice show. Of course it took a toll on my body, although not detrimental, but it was very invaluable experience to a novice and I followed a protocol very similar to the one I will share with you. As a novice, the biggest limiting factor is skill regardless of training history. Pressing is a perfect example. For 95% of people their entire training history prior to the sport involved nothing but a barbell. This makes acclimating to an axle bar easy: it's just a fat bar with no slack. Especially if there is experience in the overhead press, people typically excel in the axle press. Then they get to the dumbbell.

What the fuck is that thing? Really? It's a giant dumbbell with 6-10 inch bells, a fat handle, and you have to clean it to one shoulder and somehow get it overhead. Even with great coaching, it can take 6-8 weeks to really become proficient at the move. Block periodization can be highly effective for a novice in this scenario. The novice should focus on developing two major areas in their macrocycle: a large generalized work capacity and a proficient and engrained motor pattern for the popular events. A large work capacity is very important to allow for proper recovery between sessions and the ability to handle greater volume. This is especially important in the novice because the novel stimulus of events and strongman training will impose much greater stress on their body.

This leads to a greater compensatory stress response and inflammation associated with training. However, this is the same response that elicits “newbie gains.” The proficient motor patterns obviously will give them the opportunity to translate their work into competition. This is a bit more subjective, but a method to gauge proficiency is what the lifts look like under fatigue, either acute or residual. The body will always seek the path of least resistance. Under minimal amounts of fatigue, the athlete’s main focus is just positioning and speed, so they are more conscious of the motor pattern. When fatigue starts to settle, the priority becomes dealing with stress and form falls to a secondary or tertiary priority. Knowing this, I will often use an athlete's movement under fatigue as a more “true” gauge of that motor pattern. When they peak and recover, the motor pattern will always be fresher and crisp, and can be deceiving. The technique used under fatigue is a closer to a baseline of what they have developed neurally. That being said, residual fatigue may be a more accurate depiction of the motor pattern versus acute.

The most important difference to understand when programming for a novice of any modality is the importance of developing. Developing is very different than focusing on improvement; the methods of progression and intensity are vastly different. Think of development as a long term investment. Using a 16-week macrocycle where the novice will compete twice would be an optimal blend of competing and building the attributes I mentioned above. The major difference between the this and the 16 week macrocycle for the advanced competitor is peaking. I will demonstrate this later.

I would not plan on peaking the novice athlete. This does not mean they will not be prepared. This means there will be no super compensation methods imposed for two reasons. The first being the goal of the competition. While it would be great if the athlete placed highly, the goal of the competition is to develop skills and gain experience to use further down the line. Secondly, this 16-week training program has the same goal: to develop a foundation for the future. Super-compensating involved with peak methods are very taxing and require extra time spent on recovery after the competition. The competitions are planned out so that the athlete finishes a mesocycle, competes the following weekend, then follows a transitory microcycle that leads them into the next mesocycle.

The athlete will only be doing event specific training for eight out of the sixteen week program. They will participate in one event specific training session a week isolated as far as possible from the other training days to help facilitate proper recovery. This is a relatively low level of SPP for the athletes, considering their other training days will be foundationally based. Their events days will be a simple undulating periodized protocol that will allow for maximal learning as well as developing the specific capacity.

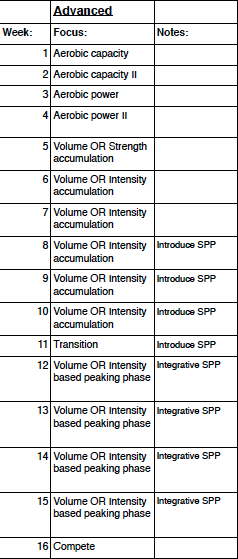

The Advanced Macrocycle

Of course, the advanced macrocycles are the most fun from a nerdy programming standpoint. However, it is also the type of program that can be dangerous to anyone who does not fit the criteria. I fell into that trap winter of my freshman year in college. I was exposed to high level programming that I simply was not prepared for. In conjunction with bad nutritional advice and an “always work harder” mentality, I was not in a good state. I was actually overtrained. Not what people think it is; I mean actual exhaustion of the adrenal gland. I couldn’t sleep yet I was always exhausted; always starving yet no appetite when I had food in front of me; gaining weight at an unparalleled rate and missing 75% of my max for a single in training. I sought medical help and was prescribed cortisol with an exercise prescription of 150 minutes a week of low intensity aerobic exercise, nothing more or less. It took me just over four months to get back to my normal lifestyle. Again this was an extreme scenario but there are still potential negative impacts if you do not objectively place yourself in a fitting program.

The advanced program is meant for an athlete looking to be competitive in high level competition. Their recovery, nutrition, lifestyle, and mindset must all be inline with the road ahead. They must have an already highly developed set of specialized skills and be aware of their specific needs, abilities and limitations.

That being said, the advanced program has effective bells and whistles that require a fine eye to program properly. The advanced athlete will be hitting a total of eight weeks of specific event work as well, but it will be programmed differently. The first four weeks will be isolated events days as seen with the novice and the second half will be integrative specific prepatory work that will be spread throughout the week and will take over as the primary stressor for the cycle.

The advanced six week accumulation can exhibit intensity or volume emphasis based on the needs of the athlete and the demands of the competition. They will also move through a transitory period leading into four weeks of a highly specialized block. This is where conjugate periodization gets sprinkled in. Based on the demands of each event, volume or intensity may be the needed stimulus to peak properly. This can get tricky, but it is needed to cater to the athlete as best as possible. Typically I will use the Verkhoshanksy shock method or cluster training with a past action potentiation pairing for this phase. This is a portion of the major difference between development and improvement. Our goal here is to win or place as highly as possible. We are looking to push the bill for performance as much as we can for this one specific show. It would require very different programming if an advanced athlete needed to do multiple high level, high stress, competitions consecutively.

RELATED: Maximum Effort Training for Strongman

Event Specific Programming

This is the curve ball in strongman programming. Based on individual difference, some shows may vary in the difficulty of the event or require very specialized work for one event. Additionally, the energy system demands of each event may be very different. While some shows do provide some consistency, there are shows where you can go from a max log, to a high rep deadlift, to a max distance carry, to a 50 feet max speed cary, back to a lactic loading event. This transitioning in an out of energy systems does not only brutalize the athlete, it can also be a balancing act to program. The anaerobic and aerobic energy systems can compliment each other nicely, but having to program for one to two highly lactic events out of a total of six or seven becomes complex.

This is where the integrative SPP work can be a detriment or saving grace. The reasoning between the integrated events versus isolated events is ultimately the amount of total volume covered. As previously mentioned, the first step in any programming is to objectively asses goals and current state. Assuming you have done that, I recommend that novices stick with the isolated events sessions until they are at the level where they are prepared to participate in high level competition. This is when they will get the most out of exposure to high level programming.

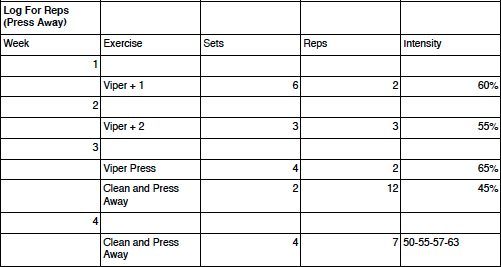

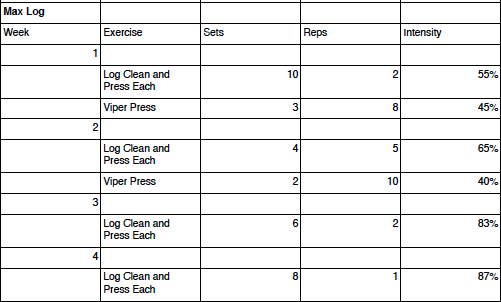

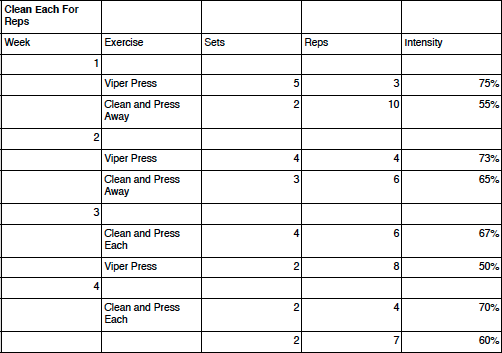

A well engrained movement pattern will not deteriorate much over the course of the six to eight weeks at the beginning of the program. During this portion of the program, generalized capacity and organism efficiency are the goal. Your training philosophy will heavily influence how you program events, but the best advice I can give you is to focus on energy system development and perfecting the movement pattern. People typically struggle with training log for events. Here are three examples on how to train log for a show over the course of four weeks.

As you can see, they are not necessarily block periodization and are slightly more linear. This is done intentionally. Four weeks of block periodization is not very effective. However, when you program to compliment your periodization methods it can be much more effective. The protocols shown move through energy systems getting closer and closer to the specific event’s demands. Event training is a very unique variable. I personally program events separately until they become integrative. At that point, the events then become the heart of the program. This is only for a three to four week period. Isolated event training is an art that I have found functions best on an inverse energy system sliding scale with linear or undulating progression schemes.

Final Thoughts

There has been a lot of information thrown at you in this article. The first being that strongman is a pretty unique sport. Nothing is ever concrete; nothing is predictable. This will always add a certain curveball to your programming. How can you effectively program for something that you are not aware of until ten weeks out? This is a part of the efficacy for block periodization in strongman. You can continually build on a set of qualities you deem appropriate for the sport over a long period of time. Then ten weeks out when the events are released, you can transition into isolated or integrative specific event work.

Additionally, I cannot stress enough the importance of objectively assessing yourself and your athletes before even beginning to write your program. Proper progressions and timing of them is critical to the development of the athlete, as well as preventing injury. By no means are the methods I outlined the only ones. Plenty of strongmen have reached the top of the sport without using these methods.

I do want you to see the beauty of programming. There are literally thousands of options available that can produce results. This is how creating your own training philosophy will give your program a unique outlook. Your philosophy in conjunction with developing a healthy coach-athlete relationship should give you great insight into what decisions to make when programming. It really is a puzzle that you have to use resources to figure out and should be an enjoyable process.

Andrew Triana was a previous intern here at elitefts. Read his log here. He is currently attending Springfield College, studying Applied Exercise Science. He competes in Strongman.

1 Comment