Years ago, in the introduction of a book about strength sports, I described four dimensions of performance: the technical, the neural, the mental, and the transcendent. The technical dimension was about motor learning and skill development. The neural dimension was about improving motor coordination, proper activation, and perfecting the harmonious and efficient execution of each sports gesture. The mental dimension was mostly about cognitive-behavioral aspects of performance and the data concerning mental rehearsal and motor mapping of movements. But when it came to the transcendent dimension, I left the reader to his own resources. It was beyond the scope of that book. That is when that “thing”— sport, training, competing—gets defined by identity descriptors and the person’s motivational architecture, which we explored in a previous series.

In another set of writings about performance, this time concerning competitive success, I listed three components: talent, preparation, and competitive readiness. Preparation was defined as comprising physical, technical, and psychological preparation. Physical preparation was presented as a set of strategies targeting nutritional, clinical, and prehabilitative preparation.

What most of us in the last few decades came to realize is that exercise in general and sport, in particular, were not only the object of different scientific disciplines and professions but also an actual object of inter-disciplinary research and practice. In other words, to achieve a better understanding and better performance results, it was not enough that a lot of people studied and worked on the subject. We needed to start talking to each other.

In this series, we will explore each one of the main disciplines and professions that deal with exercise and sport. We will introduce their approaches, language and tools, and, whenever possible, their institutional attempts to talk to each other.

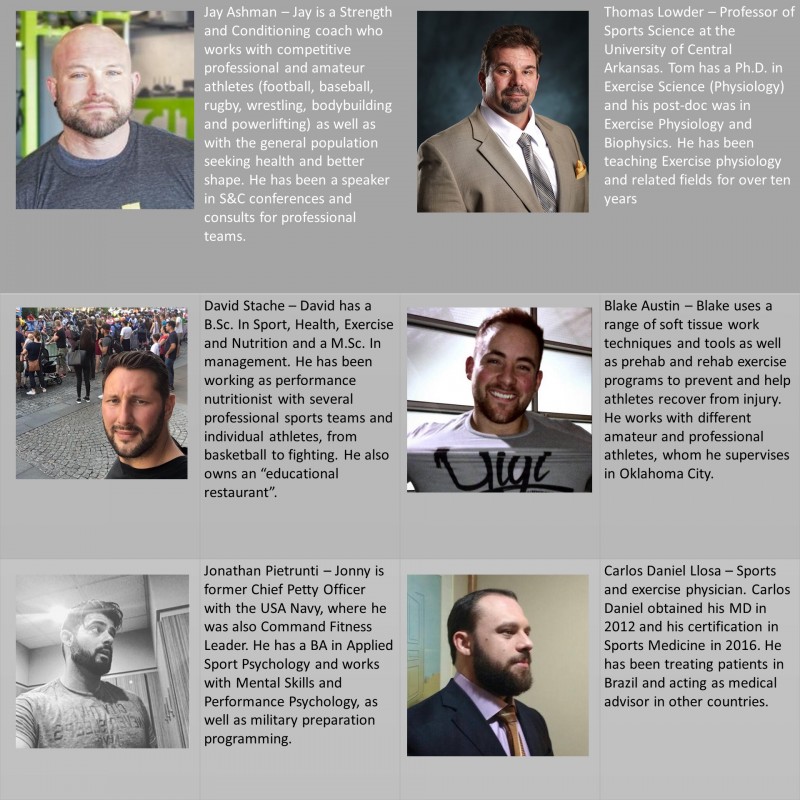

I have chosen six people to help us on this journey, each one representing one discipline or profession. My chief criterion was that they be people interested in talking outside of their professional or disciplinary realm, yet knowledgeable enough to share the challenges of their own field.

Disciplines, Multidisciplinarity, Interdisciplinarity, Transdisciplinarity

Before we present the disciplines, let’s see what the relationship between fields (of inquiry and professional practice) can look like.

Scientific disciplines are self-referenced knowledge systems for generating “true” statements about reality. They are self-referenced in all respects: they constitute linguistic systems, with self-referenced theory-laden terms; the field is socially organized in hierarchical manner according to internal legitimization and power criteria; the community establishes what is interesting and what intellectual challenges are to be pursued [i]. This was all true until about the 1970s, when this form of producing knowledge was shaken by economic trends that created both new, problem-oriented research projects, and a variety of new institutional settings where research was carried out (and not only research institutes and universities). This was called “Mode 2” of knowledge production (Gibbons et al 1994) and, in the early 1990s, “disciplinarity” (and inter, multi, trans and cross-disciplinarity) became “a thing.” To be honest, it becomes “a thing” every 10 years. The quest for this or that form of outside-the-box thinking is the new Holy Grail, but the fact that it remains difficult hasn’t changed much.

The emergence of “Mode 2” doesn’t mean the disciplinary form of knowledge production was substituted; it was complemented.

However, the idea that “a common set of axioms for a set of disciplines” can be easily established is just not true. Basically, on most issues, unless solving a specific, well-defined, practical problem is at stake, the rule is multidisciplinarity: a bunch of people from different fields work on a certain subject, but they really don’t talk to each other.

The same is true for professional fields, especially in the health sciences. You don’t need to be an epistemologist to recall, from the top of your head, situations where you saw doctors from different specialties saying completely different things and confuse the patient, or a doctor and a PT talking about an issue as if it were not the same subject.

Let me bring it down to earth for you: when you talk about “recovery” to a coach, to a doctor, to a physical therapist, to a nutritionist, and to a psychologist they will hear the term and contextualize it in their disciplinary and professional frameworks. They'll then possibly talk back to you about five different things. Let’s go even more basic: the meaning of “exercise”, “sport”, “inactivity” or "optimal healthy weight" can be completely different, according to the field.

To address a certain issue in an integrated manner, everyone involved needs to negotiate the meaning of what they are talking about. Second, they must become minimally educated in the other colleagues’ perspective. That takes time and willingness to get out of one’s intellectual comfort zone.

When it is absolutely necessary, they do it. When it is not, silly things happen, such as professionals/researchers from one field believing they have priority over the object/subject:

“Nutrition is a luxury: we need to fix this kid’s training.”

"Psychology is an ornament: we need to fix this kid’s hormones."

Nutrition is not a luxury, psychology is not an ornament, physical therapists are not magicians to be called when the kid is already broken, coaches are not crazy, and researchers are not dilettantes. If they talk to each other, they are parts of the solution to many problems in training, exercise and performance, and a key to success and health. I did not invent this; the integrative health of athletes has been a concern for a while, as well as the integration of disciplines in sports science teams (Rogerdson & Strean 2006, Dijkstra 2014). My question here is how to go beyond these institutional efforts and incorporate an interdisciplinary approach in our daily practice.

We will focus here on the term “interdisciplinarity." Multidisciplinarity has already been defined. Transdisciplinarity is often employed to refer to approaches that go beyond any disciplinary approach (Klein 2004, 2008, Russel et al 2008).

The Disciplines and Professions

These are the professions usually listed as related to exercise and performance:

- Sports Medicine

- Sports Psychology

- Sports Nutrition

- Sports Physiology

- Physical Therapy for Sports

- Coaching — Sports Preparation

- Physical Education

These are allied scientific disciplines or related professions:

- Sports Sociology

- Sports Governance

- Sports Anthropology

- Sports Biochemistry

- Sports Policy

- Physical Education

- Sport Psychiatry

- Sports Law

- Sports Management

- Sports Marketing

A comprehensive list of the professional and academic societies for each of them can be found here.

I will introduce them in an order that makes sense for the sake of the argument.

Coaching — Sports Preparation

What is the field of knowledge under “coaching”? All and none. In many countries, and the USA is no exception, coaching is a fluid profession, defined more by certain certifications than by a common educational track or field of knowledge.

An analysis of a few examples of coaching certification tests suggests that the regulating bodies consider coaching as fundamentally relying on exercise physiology, biomechanics, and varying levels of “training knowledge”, by which I mean periodization, routine planning, etc.

One of the most prestigious of such regulating bodies, the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) displays, today, the following motto, or sub-title:

“Bringing together top strength and fitness professionals.”

Until a few years ago, the motto was:

“Bridging the gap between science and practice.”

What this change means, I don’t know. The NSCA still publishes one of the highest impact index journals in the field, the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. The organization did, however, slowly drift away from the scientific production centers and now focuses more on professional coaching.

One highly coveted and also well-defined (as opposed to regulated by a license) sub-field in coaching is collegiate coaching. If we analyze the job descriptions for collegiate assistant coaches in Division I and II, and head coaches in Division III schools, for example, we observe that a Bachelor of Science degree in sports science and even a Master of Science are requirements.

Collegiate certification tests are considered tough and include a practical test where candidates are required to demonstrate proficiency in the execution of basic strength and conditioning skills, including the lifts, as well as creating a program and defending the foundations of its design.

Years ago, all major certifications were stricter and those coaches that became certified back then describe very demanding tests.

As is obvious from this outline, the field is dynamic and in permanent construction. Which direction it will take now is anybody’s guess. What we do know is that the awareness concerning the need to “talk across professional fields” is in every organization’s mind and will, therefore, influence coaching itself. The British Association for Sports and Exercise Science even offers an accreditation through “the interdisciplinary pathway” and candidates may become an “interdisciplinary coordinator.”

Sports Medicine

Sports medicine, like other sub-fields of sports health, is still in the process of carving a space in society for itself. Although most professional organizations were formed prior to the 2000s, it is generally accepted that the worldwide consensus concerning the dangers of inactivity was a major factor in promoting this medical specialty. In 2004, the World Health Organization issued its Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health.

Whether the WHO decision was a factor in bringing exercise and sports medicine to a higher public acceptance is uncertain. We do seem to be experiencing, however, a period of growing awareness about the strategic nature of exercise intervention.

Sports physicians are inter-disciplinary practitioners by definition. They need to handle issues such as musculoskeletal injuries, cardiac conditions, hormone imbalances, and the notorious “unexplained underperformance syndrome.” Up to here, they need to “talk” to others from orthopedics, cardiology, endocrinology, and general practice.

Sports Psychology

Sports psychology, still much frowned upon by those who ignore it, has a much older history of research and successful intervention in sport. The first experiments on sports psychology were published as early as 1898. Under the pioneering initiatives of Dr. Coleman Roberts Griffith, sports psychology was one of the first sports research and practice fields to be academically institutionalized (Kremer & Moran 2008).

Sports psychology was also pioneering in its efforts to talk to the coaching world. One of the first scholarly books published in the field is Griffith’s book, "Psychology of coaching: a study of coaching methods from the point of view of psychology." (1926)

It would be expected that today, almost a century after its institutionalization, sports psychology would enjoy more recognition, and its importance, not only in sports performance but also in the larger goal of achieving higher levels of physical activity in the population, more widely acknowledged.

Sports psychologists work with sports teams, individual athletes, or exercise practitioners on a variety of issues that includes goal setting, motivation, coaching, pre-performance routines, mental rehearsal, adherence to exercise programs, anxiety, self-image, and mood.

Sports Nutrition

Sports nutrition is, in academic form, as defined by their own researchers, sports physiology (Dunfort 2010). Much attention was given to carbohydrate and fat metabolism during the 1970s and 1980s. In the 1990s, nutrition as a science obtained a much higher recognition as a health-related research field in tandem with its contribution to cancer and cardio-vascular conditions.

Areas in which sports nutrition research made advances were fluid and electrolyte balance, carbohydrate requirements for endurance athletes, pre-competition foods, and recovery. There have been advances in the understanding of other athletic activities, but many unanswered questions remain concerning non-endurance athletes’ metabolism, for example (Grandjean 1997).

Unlike other sports and exercise related fields, sports nutrition is the closest to a blooming industry: that of supplements and ergogenic aids. One of the problems in sports nutrition is, in fact, being run over by fads and industry advertisement discourse (Applegate & Grivetti 1997).

Like sports psychology, there is a lack of public awareness as to what the sports nutritionist actually does and how he can assist individuals in their goals and health issues.

Physical Therapy for Sports

Although physical therapists and physical therapy related professionals are more widely sought by athletes than sports psychologists or sports nutritionists, there is much less information about sports physical therapy. Most of the issues these professionals deal with are injuries: either recovery from acute injury or managing chronic injury.

The employment of physical therapy approaches to injury prevention is much less frequent.

Sports Physiology

Welcome to the last of our sports related specialties with the one that is the hardest to define. In academic and educational terms, the big question is not what is sports physiology, but what is not. Almost everything related to human movement, with the exception, perhaps, of biomechanics and psychology, falls under physiology.

Sports physiology is the one field of knowledge that is always tested for in any sport related certification; it is one of the mandatory classes all sports-related educational programs have. As a field of knowledge, it has one of the broadest scopes.

A quick look at sports physiology curricula and books reveals that it comprises, among other subjects, nutrition, bioenergetics and energy transfer, metabolism, pulmonary, cardiovascular and neuromuscular systems, hormones, the basis of aerobic and anaerobic exercise, the molecular foundations of hypertrophy, the molecular foundations of strength building, fluid and electrolyte challenges, environmental challenges, exercise testing, ergogenics, exercise in illness, movement disorders, anatomy of skeletal muscle, muscle fiber contraction, muscle fiber types, skeletal muscle and exercise, body temperature regulation, physiological responses to exercise in the heat, exercise in altitude, overtraining, detraining, physiological responses to acute and chronic exercises in children (and other special groups, such as pregnant women and the elderly), sex difference in sports, obesity, and eating disorders (McArdle et al 2006, Kraemer et al 2011, Kenney et al 2015). I could go on.

The American Society of Exercise Physiologists defines the profession of sport physiologist as involving four areas: “Promoting health and wellness; preventing illness and disability; restoring health, and helping athletes reach their potential in sports training and performance.” In other words, everything.

It’s not easy to be a sports physiologist and, as you probably suspect, much of the interdisciplinary agenda falls on their hands. It is a powerful field. But, as uncle Ben Parker said, “With great power comes great responsibility.”

With all this said, our next chapters in this series will focus on specific disciplines, more information on them, what their work and field of knowledge consists of, and their challenges to talk across disciplinary boundaries for the benefit of the athlete, the practitioner, and the patient. In short, in understanding and assisting the human being in motion.

Acknowledgements

- Jay Ashman

- Thomas Lowder

- David Stache

- Blake Austin

- Jonathan Pietrunti

- Carlos Daniel Llosa (crapinho@gmail.com)

References

- Applegate, Elizabeth A., and Louis E. Grivetti. "Search for the competitive edge: a history of dietary fads and supplements." The Journal of Nutrition 127.5 (1997): 869S-873S.

- Barnes, Barry, and David O. Edge. "Science in context: Readings in the sociology of science." (1982).

- Ben-David, Joseph, and Teresa A. Sullivan. "Sociology of science." Annual Review of Sociology 1.1 (1975): 203-222.

- Dijkstra, H. Paul, et al. "Managing the health of the elite athlete: a new integrated performance health management and coaching model." British journal of sports medicine 48.7 (2014): 523-531.

- Dunford, Marie. Fundamentals of sport and exercise nutrition. Human Kinetics, 2010.

- Gibbons, Michael, et al. The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. Sage, 1994.

- Grandjean, Ann C. "Diets of elite athletes: has the discipline of sports nutrition made an impact?" The Journal of nutrition 127.5 (1997): 874S-877S.

- Griffith, Coleman Roberts. "Psychology of coaching: a study of coaching methods from the point of view of psychology." (1926).

- Kenney, W. Larry, Jack Wilmore, and David Costill. Physiology of Sport and Exercise 6th Edition. Human kinetics, 2015.

- Klein, Julie T. "Evaluation of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research: a literature review." American journal of preventive medicine 35.2 (2008): S116-S123.

- Klein, Julie Thompson. "Prospects for transdisciplinarity." Futures 36.4 (2004): 515-526.

- Kraemer, William J., Steven J. Fleck, and Michael R. Deschenes. Exercise physiology: integrating theory and application. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.

- Kremer, John, and Aidan Moran. "Swifter, higher, stronger-The history of sport psychology." PSYCHOLOGIST 21.8 (2008): 740-742.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. "The structure of scientific revolutions, International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, vol. 2, no. 2." (1970).

- Latour, Bruno. Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. Harvard university press, 1987.

- McArdle, William D., Frank I. Katch, and Victor L. Katch. Essentials of exercise physiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

- Rogerson, Lisa & Strean, W.B. 2006. "Examining Collaboration on Interdisciplinary Sport Science Teams." Faculty of Physical Education and Recreation University of Alberta.

- Russell, A. Wendy, Fern Wickson, and Anna L. Carew. "Transdisciplinarity: Context, contradictions and capacity." Futures 40.5 (2008): 460-472.

[i] These are general science studies concepts and can be found in Kuhn (1970), Latour (1987), Ben-David & Sullivan (1975), Barnes & Edge (1982), etc.