Disclaimer: This series is written for those that are new to the field. It is not an end all, be all on programming and periodization. It is meant to cover the basic topics and how to apply them. This is not meant to cover every aspect of said subjects, as for a new coach there is more than enough that they are attempting to learn. I have taken as many resources in strength training possible and condensed it into a "Reader's Digest" version. I am by no means the most knowledgeable person about periodization, programming, or research interpretation. The following is probably best considered as a potentially flawed but useful way to approach programming and periodization for the new coach.

Introduction

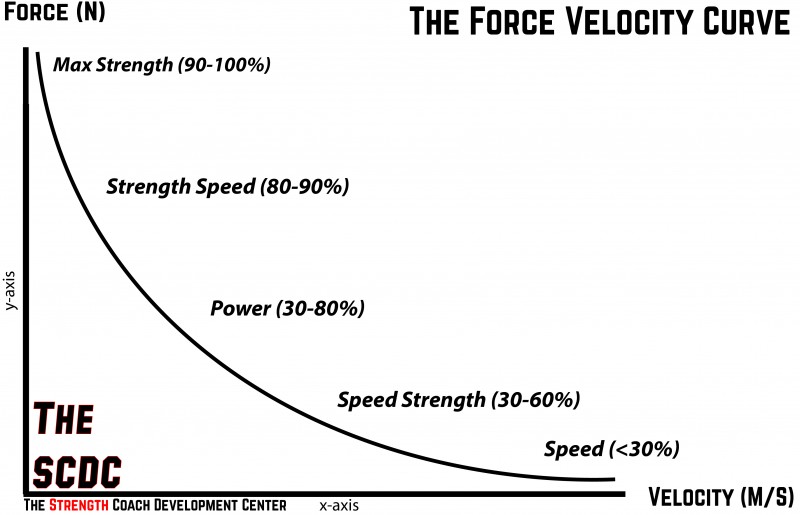

In this article we are going to go over the force-velocity curve. I know there have been many articles written about it and that we’ve all seen the charts. I want to bring a little more detail to it and its importance, and discuss how it applies to programming.

Before all you science guys jump down my throat and tell me I’m wrong or the force-velocity curve is flawed and doesn’t really work, let me say this: I understand that some things in strength and conditioning aren’t as cut-and-dry as a nice curve and line plot on a graph, and that there are other factors involved. The force-velocity curve is a concept and it is not perfect. It doesn’t represent human performance and isn’t an end all, be all. But what it does do is give younger coaches a tool for training intensities. It is a coach's job to know how to use this tool.

Part 1: The Coach's Guide to Programming and Periodization: Basic Principles and Your Exercise Bank

When I talk about the force-velocity curve to younger coaches I use force and strength interchangeably, and velocity and speed interchangeably. I will do the same in this article. I realize that this isn’t proper as far as a physics sense, but it helps young coaches grasp the concept a little bit better. I’m aware of the fact that they “technically” mean different things.

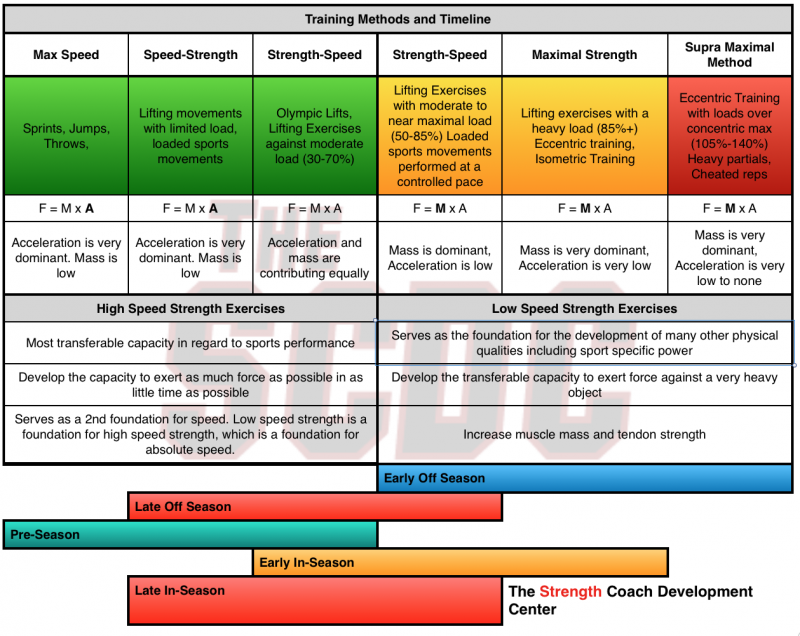

After discussing the force-velocity curve we will look at the different times of an athletes season and how the force-velocity curve applies to it.

Remember to do the assignment at the end, as it builds on the last article.

Section 1: The Force-Velocity Curve

Why is it important? Because it helps to properly program optimal training loads for the desired outcomes of your mesocycles. As a strength coach it is extremely important for you to understand this curve. You owe it to your athletes. But understand this isn’t the end all, be all. It’s a tool to help you as a coach optimize your athlete’s performance. Don’t live and die by the curve.

First a quick physics refresher:

Force (Force = Mass x Acceleration): A push or pull upon an object resulting from the object's interaction with another object. Whenever there is an interaction between two objects, there is a force upon each of the objects. Forces only exist as a result of an interaction. It can also be defined as any interaction that, when unopposed, will change the motion of an object. Force can move a body that is at rest, slow down or stop a body that is moving, or accelerate a body that is already in motion.

Velocity (Average Velocity = Displacement/Time): This tells us the speed of something but also in the direction that it is going. It’s a vector quantity, meaning both the magnitude and the direction are needed to define it. Speed is a scalar quantity, as it only describes the magnitude. Displacement is the straight-line distance from an objects starting position to its final position.

Power: The rate at which work is done. It is normally written as power = work/time, which can be re-written as power = force x displacement/time. When it comes to training athletes for team sports, we want those athletes to be as powerful as possible. Remember the velocity equation (displacement/time)? Therefore, power = force x velocity. When it comes to training athletes, if we can increase force and velocity in theory we’ve built a more powerful athlete.

Rate of Force Development (RFD): RFD reflects how fast our athletes can develop force. The faster you can develop force, the more explosive they will be, because they are able to develop a large amount of force in a short period of time.

This leads us to one of the most well-known curves in strength training.

The hyperbolic force-velocity curve, which was first discovered by Archibald Hill back in the 1930s, describes the inverse relationship between muscle force production and contractile velocity when muscle fibers are shortened. Where contraction velocity is high, muscle force is low, and when contraction velocity is low, muscle force is high. Heavy loads, slower speed. Lighter loads, faster speed. Nothing groundbreaking here.

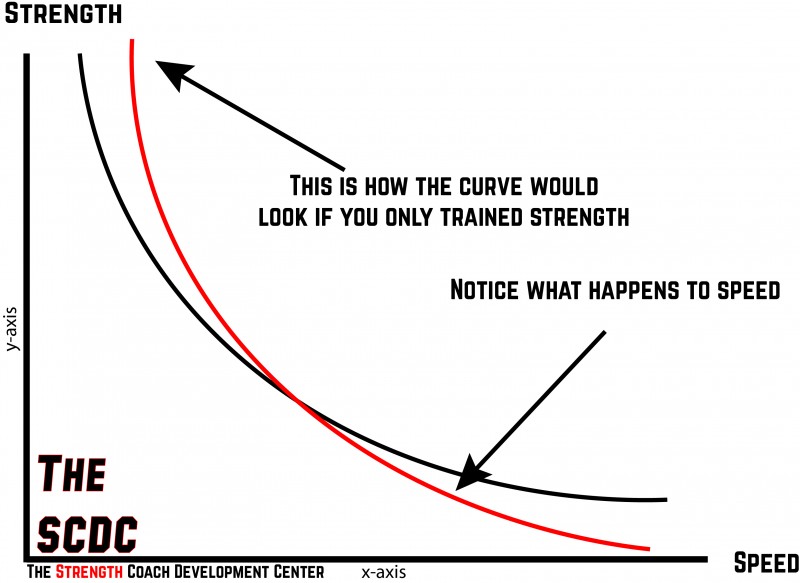

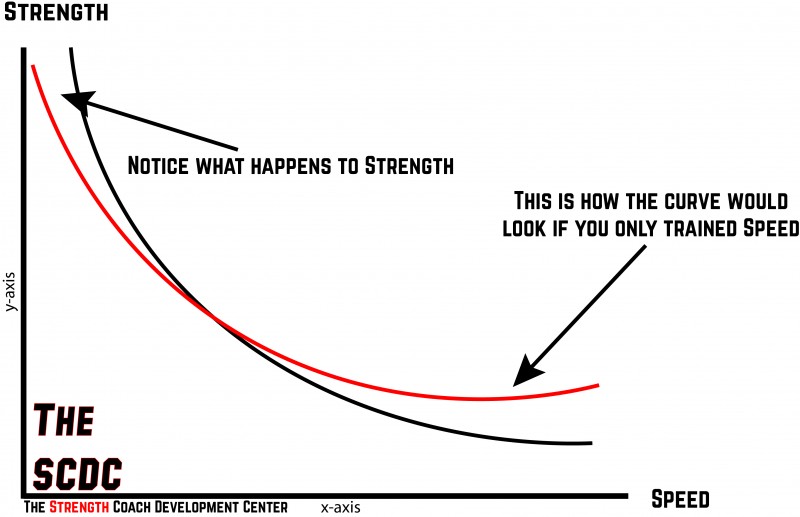

We want our athletes to be powerful, which is why we need to train both speed and strength. The ability to generate maximum strength and the ability to produce high speeds are two different motor abilities. What this means is that training pure strength alone will not necessarily enhance your athlete's speed, and training pure speed won’t necessarily enhance your athlete's strength. If you only train one part of the curve, that may lead to the athlete only improving their performance in that ability and possibly decreasing in the other.

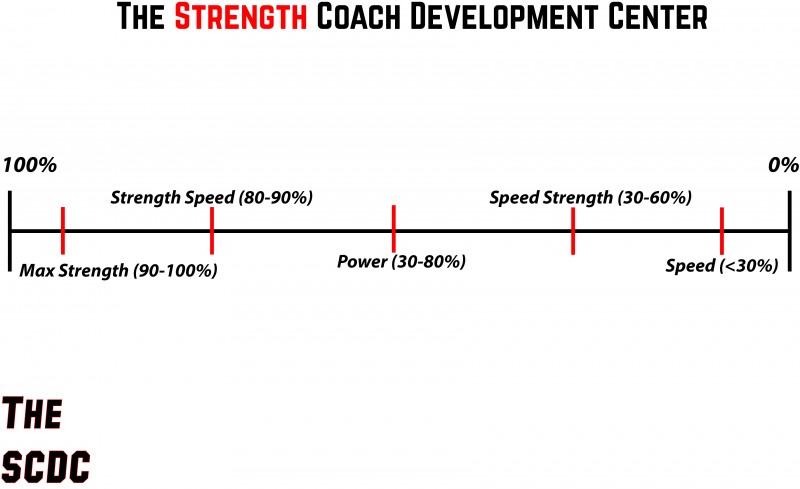

Something I like to do is turn the force-velocity curve into a straight line.

This is just a different way to look at it to help visualize things. If I’m a coach in the private setting, during the initial assessment of the athlete I will be able to see where they fall along this line. If I have a fast athlete then I know I need to do more strength-speed and max strength work with him, as we want to pull them more towards the center and make them more powerful. The same goes if I have an extremely strong athlete; I will want to spend my time doing more speed-strength and pure speed work. That doesn’t mean we won’t do strength work, it just means it won’t get as much time as the other

What about in the team setting? Well, you've gotta surf the force-velocity curve, bruh. You see, in a private setting we usually only get the athletes for eight to 12 weeks, so we have to do what’s best for the athlete. In a team setting where we have our athletes for a year, we can plan things more accordingly. Let’s look at the different zones along this curve to give you a better idea of what they are and how to use them. They are guidelines for training intensities for the goal of your mesocycles. Understand that each zone will provide different physiological adaptations that your athlete may need.

Max Strength: The max strength zone is where an athlete is able to produce the maximum amount of force through a specific movement. From a training standpoint this is programmed at intensities greater than 90% and we usually use our big main movements (squats, bench, deadlift, Olympic lifts).

Strength-Speed: This is between max strength and power. As a coach you will utilize relatively high training intensities. Strength being the first word means that this type of training leans more towards strength work. It differs from max strength in that the athlete must produce optimal force in a shorter timeframe as opposed to max strength, thus reducing the maximum amount of force that can be produced. This a good place to be to produce higher velocities with heavier weight. Training intensities are typically programmed at 80% to 90%. Variations of the main movements would be used here.

Power: This is where we can deliver peak power output. The exercises and intensities you use allow the athletes to produce the greatest amount of force in the least amount of time. This is a good place to be for increasing RFD. Training intensities are typically programmed 30% to 80%. Variations of the main lifts would be used here, but then we can start to use things like weighted jumps, throws, weighted sprints, etc.

Speed-Strength: This is between max speed and power. We won’t normally see peak force or velocity in this intensity range. Peak force is low, as there is a greater restriction in the amount of time, but what that does mean is that the velocities will be higher. You usually see this type of programming with dynamic effort days in powerlifting, but it also falls in line with most bodyweight jumps and light loads. Training intensities are typically programmed 30% to 60%.

Max Speed: The goal here is max velocity. We need our athletes to move as fast as possible when performing exercises in this zone. Most of the time the movements in this zone are typically body weight with intensities being lower than 30%. Sprinting is my main focus when doing max speed work.

How long should you spend at each stage? Well, that depends on a few things.

Age: The newer the athlete is to training, the more time you as a coach need to spend giving them a solid foundation of strength. Improvements in strength for a younger athlete will typically lead to improvements in their speed, but the stronger they get the more speed work they will need to continue improving.

Sport and Position: Most team sports will require the same things, but the position will dictate the requirements of what they need. A lineman in football may need more strength work than a running back who may do more speed-strength work. It isn't that the running back doesn’t need strength work, but think about who you want running the ball. The strongest guy or the fastest guy? Personally as a coach, I want all my athletes overall powerful, and we surf the curve depending on the time of year. It’s hard to give athletes individual attention in a team setting, which is why as a strength coach your job is to identify the requirements through a needs analysis (we will get into that in a future article) and a program based on that.

Time of Year: What time of year it is in an athlete's season will dictate load what zone you should spend time in.

Section 2: Changing of the Seasons

How you write your plan is completely up to you. But it should include the following stages: post-season, off-season, pre-season, and in-season. Within each of these stages, specific programs need to be designed. These specific programs are based on how long the time period is in 52 weeks and what the goal is for that stage. Each of these stages needs to have specific goals and objectives used to gain a positive stress adaptation and have the athlete in a better state than when they started.

The post-season is the time directly after competing has ended. This is when your training plan begins. The postseason doesn’t need to last long; two to eight weeks, depending on how much time you have, should be sufficient. Usually, teams that have a longer in-season (playoffs, bowl games, tournaments, etc.) will have a shorter post-season. The goal during this is to let the athletes rest, relax, and regenerate both physically and mentally. The exercises chosen for this period should be ones that they typically won’t perform in other aspects of their training. We want to rehab the athletes from the long season and also begin our prehabilitation programs. We need the athletes to be near 100% going into the off-season training. Understand that this is not the time to try to develop strength. We are just trying to maintain a general level of fitness while allowing the athletes to recover.

Next is the off-season. this stage can be anywhere from 10 to 30 weeks, again depending on the sport. This is the stage where we want to enhance the athlete's general physical preparedness, increase work capacity, strength, power, speed, agility, and conditioning. A good guideline in determining how long this stage should last is that it should be one to two times as long as their competitive stage (in-season). Now to determine what type of program you should run should be based on the length of the program and goals. As you progress through the off-season, the last stage needs to be designed to be specific towards the needs of your athlete's sport as they are getting close to their competitive stages of the pre-season and in-season.

The pre-season is when your athletes begin to start practices, scrimmages, pre-season games, etc. During the pre-season, we are just maintaining, as practices will be grueling. So we want the athlete's health and strength not to drop. This stage will last from the start of practices to the first real competition of the season. Your athletes need to train during their competitive stage. In-season training is paramount to not only the athlete's success but also the team's success. The goal here is to continue to improve our athlete's physical preparation for each week. We want to continue to improve strength, but remember that the athlete's practice now comes first and training in the weight room comes second. This stage lasts the duration of the season including the postseason.

During each stage, something to think about is that we are merely manipulating the force-velocity curve. And what I mean by that is that at each stage we are attempting to elicit certain training qualities along this curve.

Post-Season

Duration: 2-8 weeks

Goals: Rehab, rest, relax, regenerate. Get ready for the off-season. General conditioning is all that is needed. Nothing hard or strenuous.

Early Off-Season

Duration: 10-30 weeks

Goals: Muscular strength gains, sagittal plane dominance, teach and master movements. Force-velocity curve focus: strength-speed and speed-strength.

Focus: Increase strength and power, increase GPP, enhance mobility and flexibility, agility and speed work. Improve technical and basic skills. General strength training exercises will be the basis of the early off-season.

Late Off-Season

Duration: 10-30 weeks

Goals: Maximize strength and power development, introduce sport-specific power development, use all planes of movement. Force-velocity curve focus: power and speed.

Focus: Increase strength and power, increase GPP, enhance mobility and flexibility, agility and speed work. Tailored towards the athlete's sport. Understanding energy systems is of the utmost importance so that you can program accordingly. Anaerobic intervals that work their sport, paired with aerobic capacity training, needs to be the focus here, while maintaining a focus on power.

Pre-Season

Duration: 2-4 weeks

Goals: Optimal power development, all planes of movement. Force-velocity curve focus: strength-speed and speed.

Focus: Your athletes will now be competing in scrimmages and practices. So your training should be more of a circuit fashion. This is because of how intense the practices and scrimmages will be. Pick four to eight exercises and use movements that will help the athletes recover. These are short workouts, with low volume and intensity. Conditioning is handled by the sports coach, not the strength coach.

Early In-Season

Duration: 12-20 weeks

Goals: Rate of force development, strength-speed.

Focus: Two to three training sessions per week. We need to not merely maintain strength but instead increase strength. As in the pre-season, conditioning is handled by the sport coach, not the strength coach.

Late In-Season

Duration: 12-20 weeks

Goals: Peak power, rate of force development, sport-specific work.

Focus: Two to three training sessions per week. We need to not merely maintain strength but instead increase strength. Peak them for important games and matches. As in the pre-season, conditioning is handled by the sport coach, not the strength coach.

Assignment

Create a season chart and put into your annual plan the chart for every sport that you coach.

2 Comments