Disclaimer: This series is written for those that are new to the field. It is not an end all, be all on programming and periodization. It is meant to cover the basic topics and how to apply them. This is not meant to cover every aspect of said subjects, as for a new coach there is more than enough that they are attempting to learn. I have taken as many resources in strength training possible and condensed it into a "Reader's Digest" version. I am by no means the most knowledgeable person about periodization, programming, or research interpretation. The following is probably best considered as a potentially flawed but useful way to approach programming and periodization for the new coach.

Introduction

In the last article, we introduced some of the basic principles of programming and periodization. The principles introduced are important going forward, so if you haven’t read that article yet, please go back and read it. In this article, we will cover some strategies you can use to manipulate the volume and intensity, along with explaining training units used to structure training.

RECENT: The Coach's Guide to Programming and Periodization: Basic Principles and Your Exercise Bank

Remember that the assignment at the end is for your benefit. It’s to help you develop your tools so you can sit down and write an awesome program. By not taking the time to do the assignments, you’re only hurting yourself, as you are not giving yourself the tools you need as a coach. And if you’re not filling your toolbox with tools to help your athletes get better, it is a disservice to your athletes. As a reminder, the articles in this series will be divided into two sections: a science-based section and an application-based section.

Section I: Variable Manipulation and Training Units

Manipulation of Intensity and Volume

Variation, when applied to training, is simply the periodic alteration of training variables in order to stimulate specific adaptations and reduce overtraining potential. Remember, our goals for training any athlete are to elevate an athlete's performance, maximize specific training adaptations, and maintain performance capability for sports. We meet these goals through variation and achieve this variation of the manipulation of training variables. Remember that those variables are exercise choice, exercise order, volume, intensity, and rest periods. For this article, we will look at the manipulation of volume and intensity.

You as a coach have complete control over these variables. These variables must be ample enough over a period of time to facilitate a long-term training adaptation. Over the course of the program, we want our athletes to tolerate higher volumes and higher intensities. This is simply our overload principle. If you want to stimulate a stress response then the volume, intensity, and frequency must be sufficient. Just be careful, because if your volume, frequency, and intensity are too high for a long period of time, it may lead to possible injury or even overtraining. This is why proper recovery must be programmed into your athletes' programs.

The first variable we will look at is training volume. Training volume is the amount of work being done in either time or distance, from jumps to sprints to weightlifting. You can calculate volume per exercise, per workout, per week, etc. The second variable we will look at is intensity. This can be defined a few ways. The most common is the percentage of one's max. That’s where you break out the percentage chart and go to the prescribed percentage for that set. This can also be called intensity of load. The next variable is intensity of effort. This takes a little more knowledge of our athletes' bodies and is usually for more advanced lifters. Some refer to this as auto-regulation. In this case, you would use a rate of perceived exertion (RPE) scale. You can also increase intensity by changing the rest periods, increasing the reps, super-setting exercises etc. This is why it’s important to know the goal of the program. Intensity is essentially how hard you are working. We will get to the other three training variables in future articles.

There are several ways to manipulate volume and intensity in order to facilitate our goals. As a new coach, I want you to focus on only two for now, as these are the most common amongst most programs.

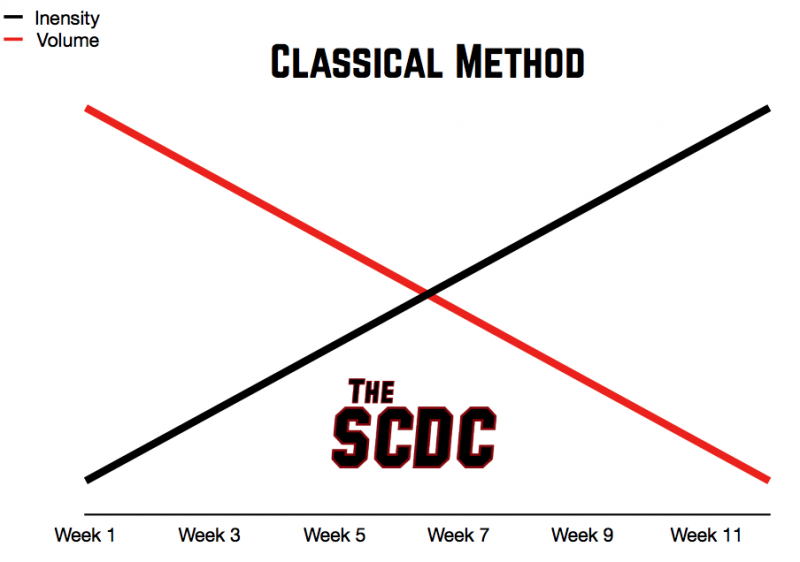

The first way we can manipulate volume and intensity is via the classical method. This is where there is a corresponding change in both volume and intensity: intensity goes up and volume goes down.

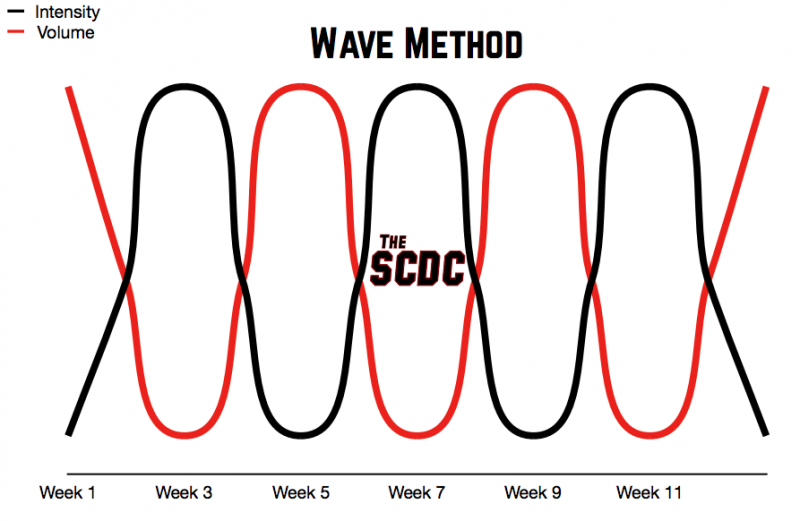

The second way we can manipulate volume and intensity is the wave method. This is where there are similar fluctuations in volume and intensity.

That’s all I want you to know for now on this topic. Know that these exist, but start thinking how it applies to your training and your athletes' training.

Training Units

In Supertraining, Verkhoshansky and Siff define periodization as, “The overall long-term cyclic structuring of training and practice to maximize performance to coincide with important competitions.” We structure and divide training into various units. Each unit will have a specific objective. Again, each unit has a specific objective. That’s an important concept to keep in the back of your mind. Everything that you do within your program has a specific objective. From the intensity to exercise selection to rest periods, they all have a purpose. Now, before we get into the fun stuff, we have to get these boring terms out of the way. The training units we use are hierarchical in nature and are as follows:

- The Multi-Year Cycle (More Than Four Years): This is a period of time that exceeds a quadrennial cycle. We typically don’t see this a lot in American culture. Think of it as taking an athlete at a young age and programming their training all the way through becoming an Olympic champion.

- The Quadrennial Cycle (Four Years, or 48 Months): This is also known as the Olympic Cycle, because "quad" means four, and Olympic Games are every four years. But another way for you as a coach to look at the quadrennial cycle is the four years of training your athlete will encounter with you at the high school or collegiate level, freshman through senior year.

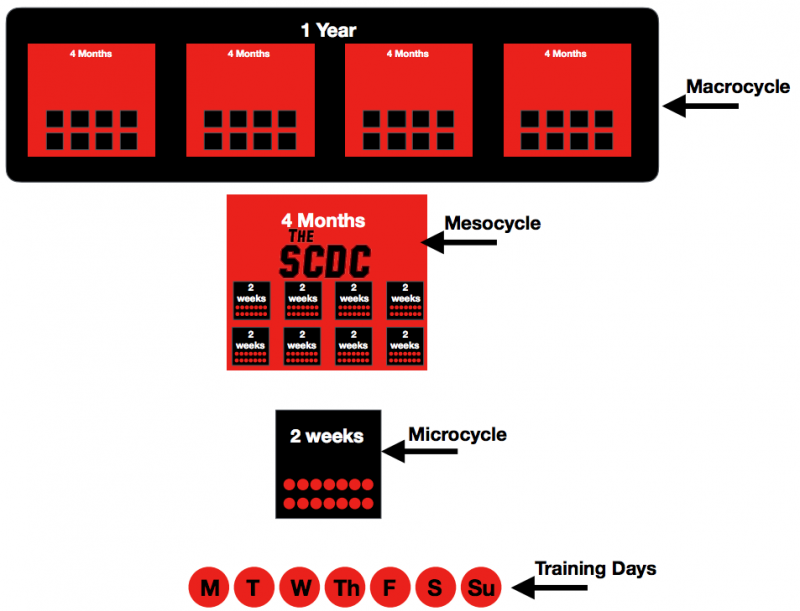

- The Macrocycle (10 to 12 Months): This is typically our yearly plan, which is divided into mesocycles (one to four months) which is further divided into microcycles (five to 14 days), which is then broken up into training days, with the training sessions making up the training day.

Here’s a visual, for those of you who are visual learners:

Section II: Building Your Annual Plan

In this section, I’m going to teach you how to design your own annual plan. This is something you will now have with you for the rest of your career. You can add to it or make it even more simplistic. As this series continues, though, we will add to it, so make sure you do this part. By developing a yearly plan it will allow you as a coach to have a foundation for the specific goals for the training year. With no foundation, we don’t have a stable structure, and without a stable structure, things don’t last very long. With a foundation in place, you can make changes as needed. Think of it as updating or renovating your house. You make these changes by monitoring your athletes, which will allow the proper adjustments to your training plan — not only for the current program but also future programs. Remember that having a plan does not mean you cannot deter from it. It is not set in stone.

When does the actual plan begin? Well, this is determined by the sport that the plan is being designed for, but your plan should begin the day after the last competition ends and the plan ends the day of the last competition of the following season. You and I could sit down and write out this awesome plan, but when dealing with athletes there are factors that arise that can throw off your plan. As a coach, you need to be prepared to handle these factors. You should list all the things that could affect a training plan when working with athletes. This includes holidays, multiple-sport athletes, fall, spring, or winter breaks, semesters or quarters, exams, length of the season, split semester sports, practice schedule, playoffs, tournaments, etc. While those are just examples, as a coach you need to take these things into consideration. Don’t spend time filling it in with anything right now.

Assignment

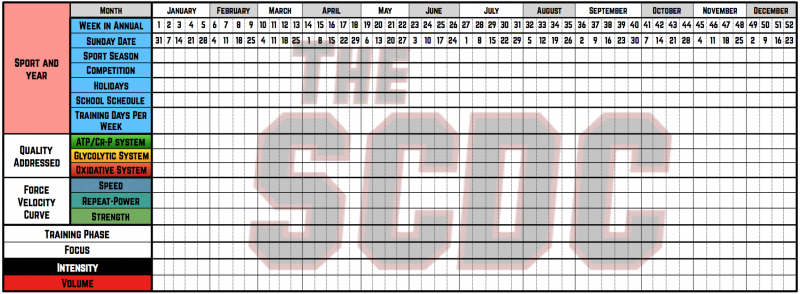

Just make a really good yearlong spreadsheet. You will use this spreadsheet with all sports. Using Excel or Numbers, create a spreadsheet like this:

This is my own personal spreadsheet. Everything on here is important to my athlete, my program, and me. Just because I have it on my plan doesn’t mean you need to have it on yours. For example, in the force-velocity curve section I know I only have three qualities listed, when in reality there are five qualities we can train along the curve. I make up for that with my intensity beneath it.

This is the setup that works for me. Create what works for you. But no matter what you create, it should include post-season, off-season, pre-season, and in-season. Within each of these stages, specific programs need to be designed. These specific programs are based on how long each stage is within 52 weeks, as well as what the goal is for that stage. Again, everything we do within these stages needs to have specific goals and objectives used to gain a positive stress adaptation and have the athlete in a better state than when they started. You should have a plan for every athlete that steps through your door on their first day freshman year until the last day of their senior year. This stuff is tedious, I get it, but that’s why we are doing these things now.

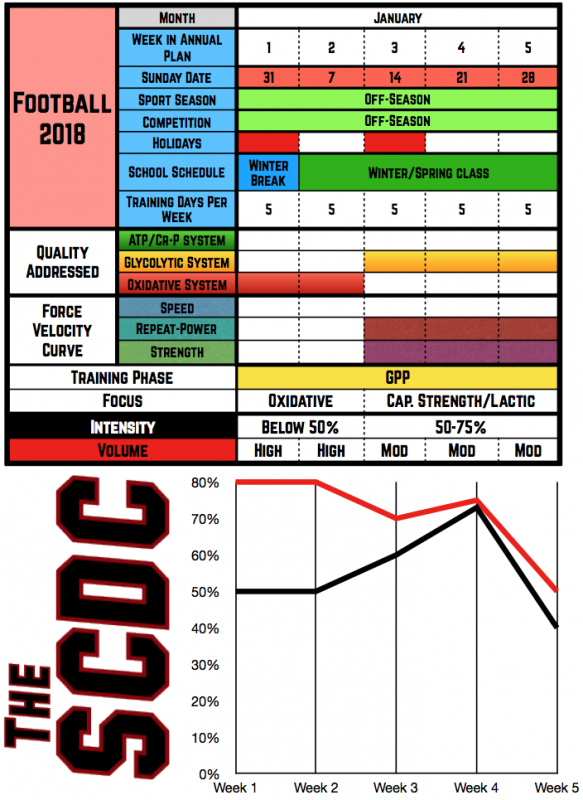

I know some of you would like to see what my spreadsheet looks like filled in, so I took part of mine for off-season football, starting in January. You can see how I’ve filled everything in. Seeing it filled in may also help some of you understand my thought process and why I set it up this way.