training

The 7 Deadly Sins of Training (And How They’re Killing Your Progress)

Most lifters don’t stall because their program sucks—they stall because their habits do. These are the 7 “deadly sins” of training that quietly wreck your progress and what to do about each one.

From 'Old Man' Knees to a Fitness Revolution: The Story of KneesOverToesGuy

Ben Patrick discusses how he overcame chronic knee issues that began at age nine by utilizing backward sled drags and eccentric loading to rebuild athletic resilience. The conversation bridges the gap between Westside Barbell principles and Patrick's "Knees Over Toes" methodology, exploring how scaling exercises like the split squat and seated good morning can facilitate longevity and pain-free movement.

4 Pro-Level Secrets for Using Floss Bands and Knee Wraps Most Lifters Get Wrong

Master the use of floss bands to achieve pain relief and increase range of motion through compression, tack and stretch, and blood flow occlusion in joints like the shoulder, elbow, and wrist.

A One-Time Chance to Join the Table Talk Crew for Life

The Lifetime Table Talk Crew Membership is open again — and likely for the last time, giving lifters and coaches a one-time chance to lock in all-access membership for just $299. No renewals, no monthly fees, just lifelong access to exclusive content, community, and support that fuels the future of the Table Talk Podcast.

The Education Echo

Everyone starts somewhere. Early on, it’s easy to look at newcomers and forget you were once guessing too. The difference between arrogance and experience is humility. If you’ve been in the game long enough, you realize the next wave isn’t your competition — they’re your continuation.

Why a 'Crazy' Mindset Wins: 5 Raw Truths on Strength and Creativity from an Unlikely Mentor

"I remember just taking that bar and exploding so fast off my chest I want to throw it right through the ceiling... it's like a drug right it's like holy fuck i just hit 405 like 45 pounds... and nobody even knows this except for me. I'm 42 years old why do I keep doing this... but it's all I know it's the greatest feeling in the world man."

THE BEGINNER SERIES: THE LIFT-OFF

In the world of powerlifting, there are many factors within your control: perfecting your technique, maintaining consistency in your training, staying fully engaged in your program, prioritizing proper nutrition, and valuing recovery as much as the time "under the bar."

The Man Who Refused to Be Done: The Jared Maynard Story

Strength coach and powerlifter Jared Maynard battled a rare, life-threatening disease (HLH) that caused total organ failure, requiring five weeks on life support. At the same time, doctors advised his family to prepare for goodbye. Despite being left legally blind, skeletal, and wrestling with profound grief, he returned to the powerlifting platform, embodying the powerful message: "You're not done yet".

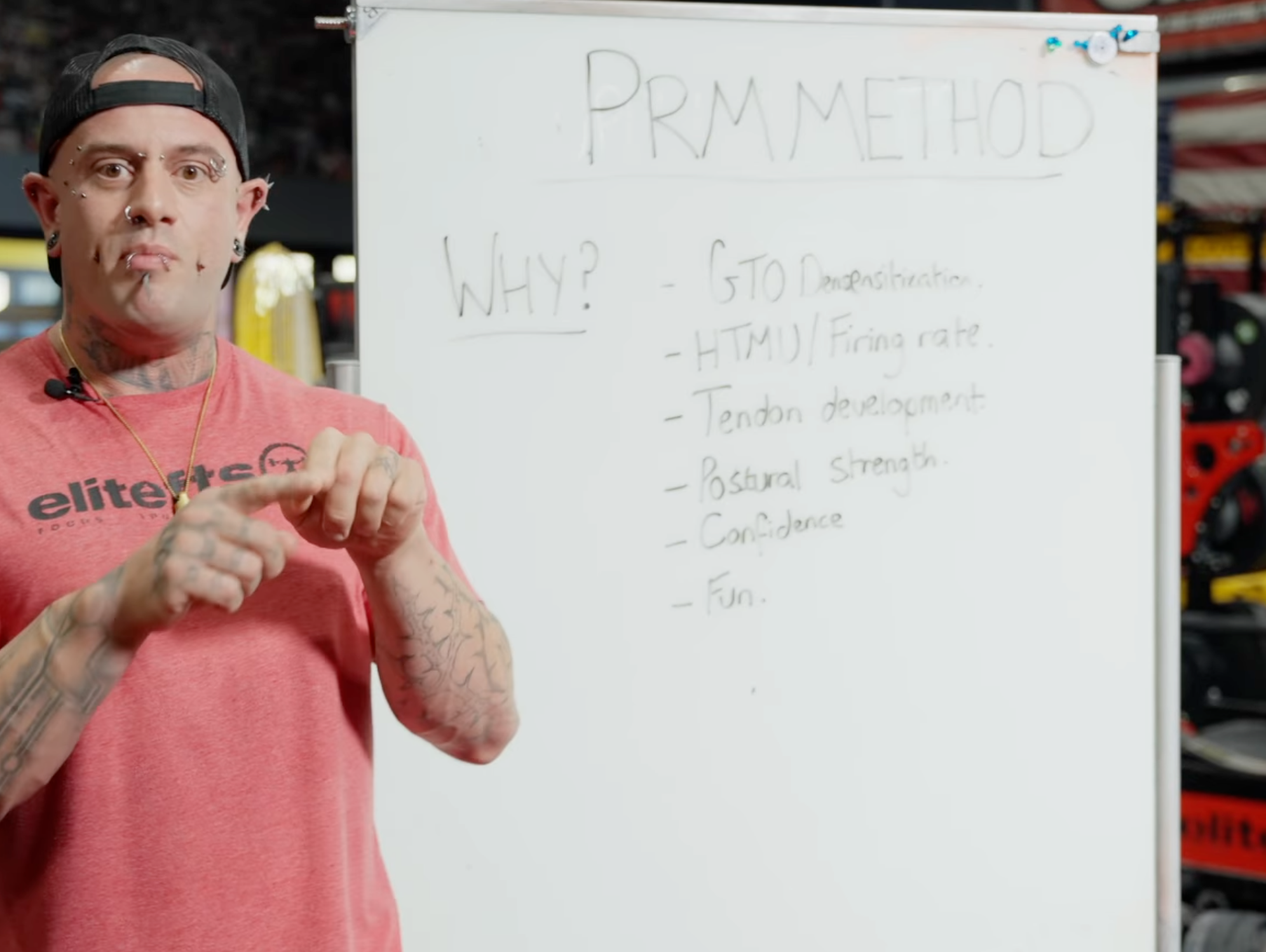

5 Counter-Intuitive Lessons on Strength from a Method Born in a Backyard Hole

This approach provides several key benefits, including the desensitization of GGI tendon organs, improved recruitment of high threshold motor units, and a significant boost in confidence when handling super maximal loads, leading to direct carryover to the full main lift

5 Counter-Intuitive Strength Lessons From a Coach Forged by Injury

Locke’s Kodiak Barbell method is a blend of conjugate, block, and DUP principles, built around diagnosing an athlete's failure as either structural (postural) or muscular. Structural failures are addressed by systematically using variations, tempo, and pauses, while muscular failures involve programming targeted accessory movements to strengthen specific weak links.

You're Doing the McGill Big Three Wrong. Here's the Secret You're Missing.

The McGill Big Three exercises: the curl-up, side plank, and bird dog are designed to challenge your core from different directions, with the ultimate goal of creating stiffness in the spine and the surrounding musculature. For both strength enthusiasts and those with low back pain, prioritizing the proper intent, maintaining a neutral spine, and ensuring alignment of the rib cage and pelvis are absolutely paramount for stability and maximizing carryover.