Recently, I watched a video that has been making its way around social media, in which Joe DeFranco discusses the shortcomings of many football conditioning tests. You’ve probably heard of these, or maybe you were lucky enough to actually endure them as a high school or collegiate athlete: crazy sets of 110-yard sprints, the 300-yard shuttle, or sideline-to-sideline ”gasser” tests. Joe’s argument is that football is an aerobic-alactic sport, so why are those notorious conditioning tests not set up to test the demands of the sport?

I think there are a few reasons for those tests still being prevalent. First, they’ve been done forever. The sport of football can be extremely resistant to change. Second, these tests are easy to administer. They require little more than a few sets of eyes, a field, and a stopwatch. Finally, designing a new conditioning test is hard work that requires a lot of trial and error. Despite all that, the football strength and conditioning staff at Princeton set out to design a better, more specific conditioning test last year.

RELATED: Why Do We Test the 40-Yard Dash at the Combine?

When I first arrived at Princeton University, our preseason conditioning test consisted of repeat 40-yard sprints. The test consisted of 14 reps with 45 seconds rest between reps. Times were based on your best 40-yard dash time from the spring. We had the aerobic-alactic part down, but we still felt like there was room for improvement. When we ran the repeat 40 test we wound up having to ballpark the times, as it would be impossible to stop the watch at the tenth of a second cutoff. As a result, we wanted to create a test that would be easier to administer. We also encountered a number of guys pulling up mid-test due to hamstring pulls, so we needed a test that would lead to fewer soft tissue injuries at the start of camp. Another goal was to find a way to have our “bigs” (C Group, below) cover less ground during the test.

We began experimenting after the season with having our “bigs” run 20-yard sprints instead of 40-yard sprints, but found that more explosive guys would get off the line hard and then coast. Another issue was that with the shorter work interval came a shorter rest interval, and by the time that 300-pounder slowed down and got back on the line for the next rep, he was already late.

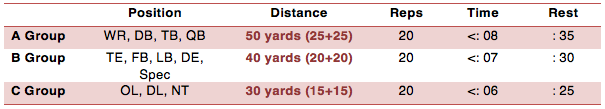

This led us to implement a short 30-yard shuttle (15 yards down and back), which proved to be an equalizer for our explosive “bigs”, as they would now have to decelerate into the turn and accelerate out. The work interval is also longer, which allows a longer rest period and gives the guys time to get back on the line before the next rep. We liked the test so much that we extrapolated the times and distances for the rest of the team and completely overhauled our test. We also required our guys to hand-touch the line on the turn of each rep — right hand for the first 10 reps, left hand for the last 10 reps. We ended up with the following:

This protocol allowed us to test the correct energy system for football and reduce injuries. Since the athletes never had to open up for a long sprint, we didn’t see a single soft tissue injury while administering the test last fall. We also found that it was significantly easier to administer than the repeat 40-yard sprint test, and our guys were better able to train this test if they were away from campus for the summer. While it doesn’t have the same nostalgia to it as the 300-yard shuttle or old school gasser test, our position coaches easily saw the practical application, and the test was challenging enough that we felt it accurately revealed who was ready for camp.

Terry Joria is in his first year as the Head Football Strength and Conditioning Coach at Princeton University. Joria has been at Princeton University since September 2014 in an assistant strength coach role. Prior to Princeton, Joria was a graduate assistant and an assistant strength coach at Illinois State University, where he received his master's degree in 2013. He can be contacted at tjoria@princeton.edu.

Header image courtesy of Ievgen Onyshchenko © 123RF.com

2 Comments