A common question I receive is “How do I make my own muscle-building diet?” This is a complex question, but today I’m going to answer that and take you through the complete step-by-step process. By the end, you’ll have a complete nutrition program set up and ready to go.

We’ll also cover what to do after your diet ends, which is a topic that is hardly ever addressed but is critically important for maintaining your gains.

RELATED: Nutrition, Supplement, and Drug "Facts" Explained

Finally, we’ll cover how to integrate this process so you can rinse and repeat until you reach your desired body weight.

At the end of this article, all of the major points will be summarized into a step-by-step process of 10 bullet points that will take you from zero to having your complete kick-ass diet ready to go.

Why You’re Not Gaining Weight

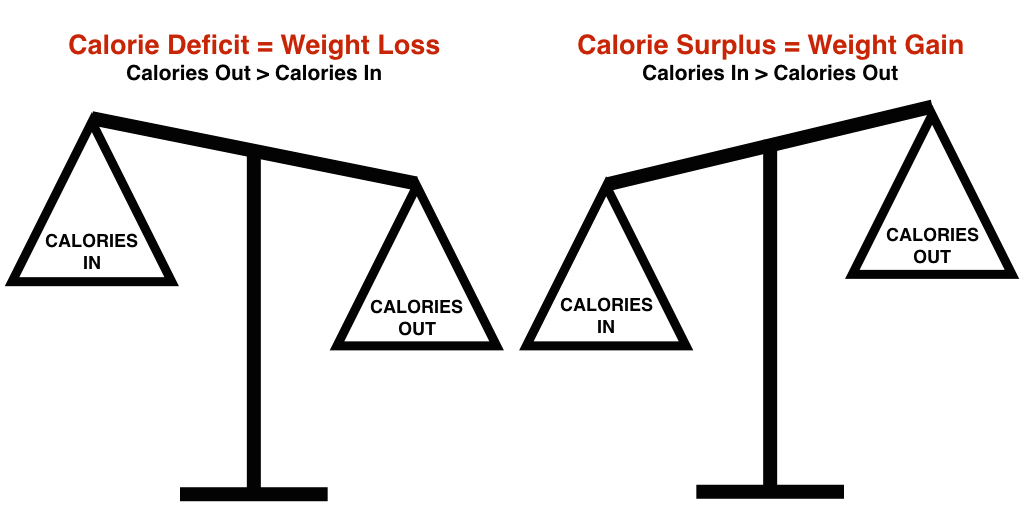

The only factor that directly regulates bodyweight is your caloric intake, often referred to as energy balance (1). Energy balance describes the relationship between the total amount of calories consumed via food and drink in comparison to the number of calories you expend throughout the day via metabolism and physical activity. Essentially, if you consume more calories than your body burns throughout the day, you will gain weight (this is referred to as a caloric surplus); if you consume fewer calories than your body burns throughout the day, you will lose weight (this is referred to as a caloric deficit).

This is an important concept to understand because it simplifies things. If you’re not gaining weight, regardless of how much you think you’re eating, you’re not in a caloric surplus. Utilizing apps like My Fitness Pal can be useful, but at the end of the day, they’re still just estimations and may not be accurate (2). So if the app has you eating at a 500kcal surplus and you’re not gaining weight, it just means your energy requirements are higher than what the app estimated. So, in this case, what we need to do is create a new surplus.

How to Determine the Correct Surplus

The optimal rate of weight gain for a beginner or intermediate bodybuilder is 0.25 to 0.5 percent of your bodyweight gained each week, and for advanced athletes, the rate will be slower (3). This rate of weight gain will maximize gains in lean mass and minimize fat mass accumulation. A 2019 paper titled “Nutrition Recommendations for Bodybuilders in the Off-Season” recommends introducing a caloric surplus of 10 to 20 percent (3). This means increasing your maintenance caloric intake by 10 to 20 percent. There are many equations to calculate caloric intake, but since they are all inaccurate to some degree or another, they are just a starting point.

To set initial calorie targets, I use the following equation: body weight (kg) x 30-40. I’ll use myself as an example. My current body weight is 127kg (278.0 pounds), and I’ll choose to multiply that by 35 because it’s right in the middle.

127 x 35 = 4,445kcal

Here’s why it’s important not to get too attached to the numbers you get from these equations. My actual maintenance calories are 3,300kcal, which is a 1,105kcal difference from the result above. Every other equation I’ve used is also way off, but either way, it doesn’t really matter because it’s just a starting point. I will say that I am an outlier, and my energy intake relative to my body weight and level of activity is very low. But it is what it is.

From an evolutionary perspective, bodyweight fluctuations are not favourable, so we have developed significant adaptive processes to mitigate these alterations (4). This means that your maintenance energy intake is not always a static number and can actually be more of a range. Using myself as an example again, my maintenance range is from 3,100-3,700kcal. This means if I consume any amount of calories within this range every day, I will not fluctuate in bodyweight.

Everyone has their own range, and the breadth of the range will vary from person to person. Knowing this, we can establish a predetermined timeline to measure progress before making further adjustments. I generally recommend increasing calories at a frequency of at most once every four to six weeks.

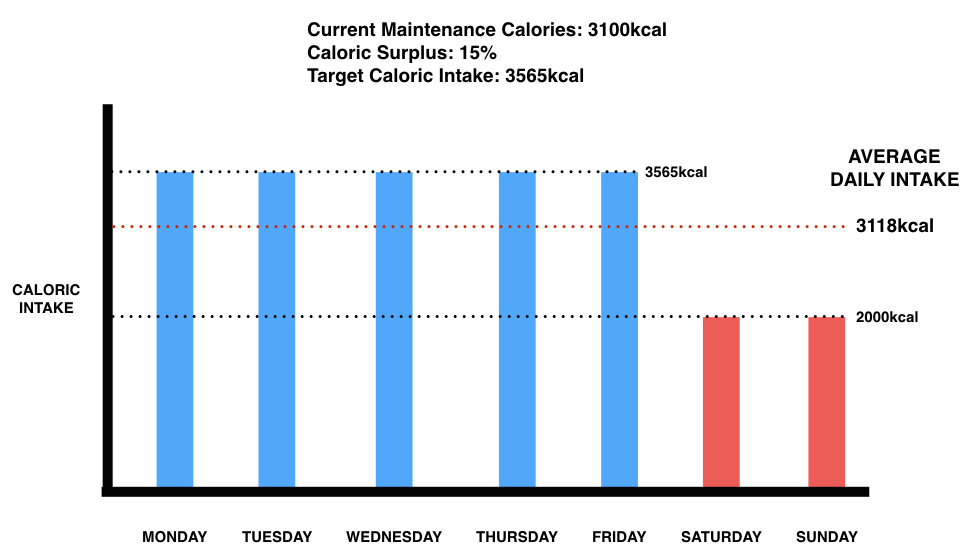

This is in part because most people need time to establish consistency in their diet in order to begin seeing progress, but also because it takes time to determine how your body is responding to the surplus. Changes should only be made if your bodyweight stalls for a period of two weeks; this period is to ensure the stall is not simply a result of measurement error or a reduction in adherence. Caloric intake within a 24-hour period is important, but so is your weekly caloric load. If you follow your diet throughout the week, but over the weekend you fail to hit your caloric requirements, it can literally undo all of your hard work.

The diagram below gives a visual representation of this.

In the diagram above, the individual’s maintenance caloric intake is 3,100kcal. However, since over the weekend, they failed to reach their calorie target, it reduced the daily average throughout the week significantly enough to prevent any potential weight gain. Ensuring consistency throughout the entire week is necessary to ensure you’re gaining lean mass.

Setting Up Your Macronutrients

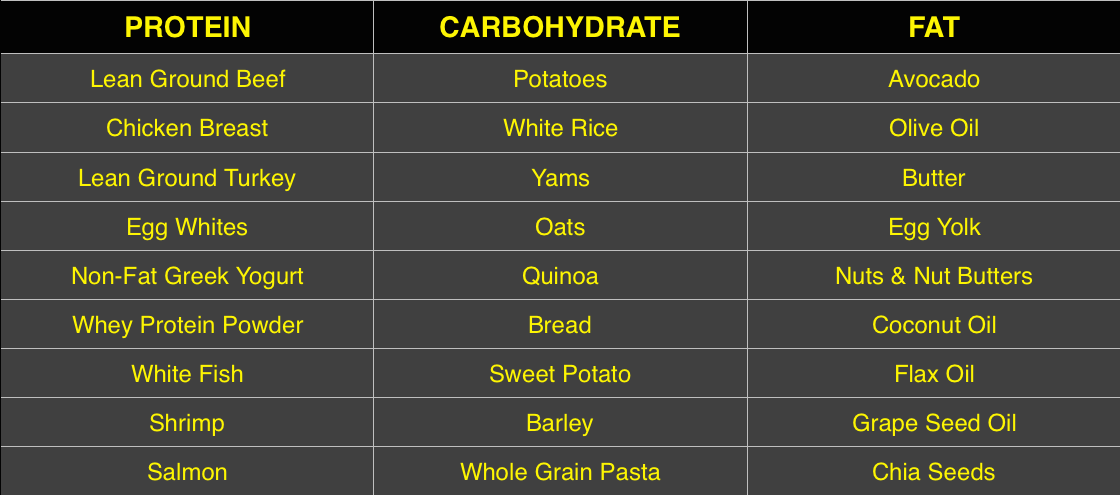

Macronutrients are the primary source of energy we receive from our diet and are comprised of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats (5). When it comes to weight loss virtually all diets produce near identical results when calories are equated (6). However, there are significant differences in body composition that can occur when comparing diets that preference certain macronutrients over others. Weight loss diets that involve high protein intake often increase lean body mass and decrease fat mass to a much larger degree than low protein interventions (7). With regard to building muscle, a lot of the same rules apply and the ratio of fats, carbohydrates, and protein is important.

- Carbohydrates: Carbohydrates function as the primary fuel source for your muscles. As one paper wrote, “A high-carbohydrate diet remains the evidence-based recommendation for athletes who engage in hours of physical activity on a daily basis... Consumption of a variety of carbohydrate foods ensures adequate muscle and liver glycogen restoration between bouts of physical activity” (8). Essentially what this means is that carbohydrates play an important and complex role in optimizing athletic performance especially as exercise intensity increases.

- Fats: Dietary fat is a critical macronutrient with a wide array of functions, ranging from supporting cell growth to hormone regulation. However, once the minimum daily requirement has been met, the impact on performance of increasing fat intake is in some cases neutral but more often negative (9) (10) (11). From a performance standpoint, it is better to preference protein and carbohydrate intake over fat.

- Protein: Proteins are molecules that act as building blocks for many tissues and metabolic functions. The most notable functions of protein with regard to this article are its roles in building new muscle mass (7) and triggering the muscle protein synthesis (MPS) response, which is the primary impetus for muscle growth (12).

Below is a non-exhaustive list of high-quality foods from each macronutrient category:

A paper by Iraki et al. makes the following recommendations for macronutrient consumption (3):

- Protein: 1.6-2.2g per kg of bodyweight consumed per day

- Fats: 0.5-1.5g per kg of bodyweight consumed per day

- Carbohydrates: at least 3-5g per kg of bodyweight consumed per day

The following are not macronutrients but are important and are good general guidelines:

- Fiber: 30-40g per day

- Water: 0.7oz per pound of bodyweight

Integrating Meal Timing and Frequency

Meal timing has gone through phases where one week it’s touted as the be all end all, then the following week it gets dismissed entirely in place of total protein and calorie intake. The truth is both groups are right but to varying degrees. Meal timing and frequency with regard to body composition account for roughly five percent of overall results, according to Dr. Mike Israetel (13). This brings up two very important perspectives. The first is that since adherence is of critical importance to the long-term success of dietary intervention, a tactic that requires significant time investment but produces only a five percent improvement may not be worth the effort for some individuals.

On the other hand, if you don’t find it inconvenient, a five percent improvement is nothing to scoff at. So why not take advantage of this tactic if it’s available to you?

This is a strategy that comes down to the individual, their long-term goals, level of dedication, and what they are willing to sacrifice. Both perspectives are correct; it just depends on the circumstance.

With regards to meal frequency, the research shows two meals are better than one and three meals are better than two when calories and protein are equated. But beyond that, there really doesn’t seem to be any significant benefits of increased meal frequency outside of very specific circumstances (14). So, once again, it comes back to individual preference. If you feel better eating smaller, more frequent meals throughout the day, that’s fine. If, however, you choose to stick with three larger meals, that’s also fine.

I sometimes encounter pushback on this idea because anecdotally pro bodybuilders tend to eat seven or more meals per day. The reality is these athletes need to consume upwards of 6,000kcal daily. It would be very impractical to attempt to consume everything in just three meals. Add the use of anabolic sport supplements, and you’ve now just increased the complexity of the conversation. But for natural lifters wanting to get maximally jacked, three or more meals seem to be sufficient.

Next, we can look at the post-workout anabolic window. This is the holy grail of muscle growth for many people. Research conducted by Krieger et al. found that in order to maximize MPS post-workout, you only need to consume 20 to 25g of protein either just prior and/or after training (15). However, there is no detriment to consuming more than 25g per serving and contrary to common thought it will not simply be “wasted.” In fact, a 2017 study by Young Kim et al found a benefit to consuming up to 70g of protein in a single serving: “as in the healthy young adults, we found in older adults that the whole body anabolic response increases linearly with increasing amount of dietary protein without showing a sign of plateau, largely through a greater suppression of protein breakdown” (16).

READ: Fat Loss Advice That Is Complete Bullshit

Consuming a mixed protein intake where servings range from 25 to 70g can positively impact the anabolic response to muscle growth through various direct and indirect mechanisms. This is especially relevant for individuals at a heavier body weight since logically it makes sense that a 250-pound male would have an increased requirement for protein per serving than a 125-pound female.

Iurii Golub © 123rf.com

It’s also important to note that the anabolic window is not limited to 30 minutes as most people assume. Research conducted by Brad Schoenfeld and colleagues demonstrated that the post-workout anabolic window is likely closer to several hours (17). This is helpful because in the case where you forget your protein shake at home, you won’t lose any gains.

Supplements

Supplements can be beneficial for building muscle. But it’s important to remember that they are only there to add a small benefit to an already well-balanced diet. However, supplements will not fix bad nutritional habits. In his book, The Renaissance Diet 2.0, Dr. Mike Israetel suggests that supplements can impact overall body composition results by roughly two to five percent (13).

The idea that a magic supplement is the secret to getting jacked is just not true. That being said, research does show that specific supplements have some added benefits to building muscle.

- Protein Powder: Sufficient protein intake is a prerequisite for increasing muscle mass (18). If you struggle to meet your daily protein requirements, supplemental protein can have a big impact on your progress.

- Creatine: Creatine is another supplement that has a significant positive impact on hypertrophy (19). Although all of the mechanisms are not fully understood, it’s hypothesized that results come from its impact on muscle protein synthesis and myogenesis (the building of muscle) (20). A dosage of 5g daily is sufficient to gain the benefits from this supplement.

- Caffeine: Caffeine has ergogenic (enhancing physical performance) properties, which may decrease pain and perceived effort and increase anaerobic performance (21) (22). As a result, many athletes and bodybuilders in particular use caffeine to gain performance enhancements (23). A 2019 study found “an [performance enhancing] effect have used high dosages of caffeine (5 to 6mg per kg) which is at the upper limit of what is considered a safe dosage” (24) (25). This is typically the recommended dosage to see performance benefits and should be taken roughly 30 minutes prior to training.

There are potential cases to be made for a few more supplements, but in my opinion, the research hasn’t convincingly demonstrated an effect on performance and/or muscle growth yet.

Measuring Your Progress

An expression often attributed to Peter Drucker is “You can’t manage what you don’t measure.” With regards to building muscle, it’s absolutely critical to have a measurement system in place. This is important for two reasons:

- If you don’t monitor your rate of weight gain, it might be too fast leading to higher levels of fat accumulation.

- If you don’t monitor your progress, you may look more muscular subjectively, but after three months, you haven’t actually put on any appreciable size.

Although measurements are important, it’s equally important to understand the utility and limitations of different measurement forms. For the individual whose primary goal is to gain muscle and minimize fat accumulation, the tools I would recommend are the following:

- Bodyweight scale

- Photos

Things like calipers and DEXA can also be valuable but they certainly are not necessary. Plus there’s also the issue of convenience and potential measurement error. Virtually everyone has access to a scale and all phones now come equipped with cameras, so from a practicality standpoint, these measurement tools are very good.

MORE: Popular Diets, Simplified

Sergey Rasulov © 123rf.com

Body weight fluctuates throughout the day, and the time of day you measure can be the difference of five to fifteen pounds. These fluctuations primarily come from differences in hydration and food in your system and are also observed in women during menstruation. So ensuring that there is a consistent time of measurement can eliminate most of the inconsistencies. Take your bodyweight naked first thing in the morning, after you go to the bathroom and before you eat or drink anything. Do this daily, and at the end of each week, take the average. The reason to use averages rather than weighing once per week is accuracy. If you weigh yourself on an off day where you are heavier or lighter than usual, it will alter the data. This means you may choose to adjust calories based on inaccurate information, which can either prevent you from gaining weight or make you gain weight far too fast and become fat.

Using averages smooths out a lot of these inaccuracies. If your weekly average is going up by slower than the recommendation of 0.25 to 0.5 percent each week, it means you need to increase your calories. If the average is going up by more than 0.5 percent per week, you might need to reduce your calorie intake. After you make the necessary adjustment, just repeat the process until you are gaining weight at the recommended rate. If from one week to the next you plateau, before making an adjustment, ask yourself if the stall is due to lack of adherence or because it’s time to increase calories. If you’re unsure, just wait another week. Then, if your weight goes up, you know it was likely due to measurement error; if your weight is still stalled, you know it’s time to increase your calories again.

Photos should be taken at the same time: First thing in the morning and ideally with natural lighting. Don’t use filters or different lighting to trick yourself into seeing progress that just isn’t there. I would take photos once every two weeks or once per month. If you take pictures more frequently than that, you will likely not see any significant changes.

The Importance Of Maintenance Phases

A maintenance phase with regard to dieting is where you intentionally maintain your bodyweight for a predetermined period of time. People don’t often associate the word maintenance with progress, but maintenance phases play a critical role in successful dietary interventions. As previously mentioned, your body is resistant to fluctuations in weight, and in many cases, it will adapt to prevent fluctuations that veer too far from baseline (26).

Maintaining a new bodyweight allows your body to reset its homeostatic line. Essentially, it accepts your new weight as the baseline, which minimizes fluctuations up or down. This is also important because it will improve muscle retention during a cutting phase where you are at greater risk of muscle loss.

There are also several psychological benefits to a maintenance phase. Knowing there is an end date tends to make the difficult process of dieting more manageable for many people. During a maintenance phase, the objective is to maintain your bodyweight intuitively. You can do this by weighing yourself daily and ensuring your weight doesn’t fluctuate more than one to three pounds from your baseline. This reduction in tracking various metrics can come as a welcomed break for many dieters.

LISTEN: Table Talk Clip — Are Cheat Meals Worth It?

One paper found “Intuitive eating consistently predicted lower levels of disordered eating and body image concerns” (27). In addition, neuroticism is often associated with eating disorders (28) and maintenance phases allow a reprieve from tracking and other behaviours that are sometimes associated with neurotic perfectionism (a predictor of disordered eating) (29).

I tend to agree with the approach Dr. Mike Israetel takes, which is to have maintenance blocks lasting two-thirds of the length of the diet (13). So, if you diet for three months, your maintenance will last two months before returning to another dieting block.

Andriy Popov © 123rf.com

Andriy Popov © 123rf.com

When To Cut And For How Long

The purpose of a cutting phase is to reduce body fat while preserving muscle mass. So, you’ve spent three to four months building muscle at the recommended rates of weight gain. You’ve finished your maintenance, and now it’s time to shed some of the fat you accumulated during your bulk. The way to structure your cutting phase is quite similar to a massing phase.

A paper by Helms et al. titled “Evidence-Based Recommendations For Natural Bodybuilding Contest Preparation: Nutrition And Supplementation“ recommends losing at a rate of 0.5 to 1 percent of your body weight each week (30). Protein intake is often higher during a cutting phase to minimize muscle loss. Recommendations are 2.3 to 3.1g per kg of lean body mass per day (30). The length of the cutting cycle should not extend much beyond three months in length, or you risk diminishing returns at a significantly increased difficulty (13).

After the cut, you complete a maintenance block that’s two-thirds of the duration of the cut. This is followed by another massing phase. Then simply repeat this process until you’ve reached your ideal body weight and composition.

Important Considerations When Dieting

Self-determination theory (SDT) recognizes “a consideration of innate psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness” (31). Each of these is a type of intrinsic motivation, and rather than focus on how much motivation you have, it’s critical to understand the types of motivation instead. When evaluating the effectiveness of any dietary intervention, the individual’s experience and final outcome trump most other things.

The reason I place significance on the experience is if you absolutely hate the dieting, even if you reach your goals, there’s a high probability your adherence will drop off and you will regress back to your old state. But when you find enjoyment in the process, long-term maintenance becomes much more realistic. One of the primary reasons the failure rate of diets is 85 percent is because the dieters in question are incompetent. I don’t mean this as an insult; I just mean they don’t have the right education and experience in this area.

For example, think of your absolute favourite exercise. Most likely it’s something you’re already good at. Everyone has a genetic predisposition for certain exercises over others, and it’s common to be drawn to train exercises where we have a natural predilection. This will inspire you to further increase your competency, increase your motivation to work harder, and increase your success rate proportionally.

Knowing this, it’s important to accurately evaluate your starting point (how competent are you?), the difficulty of the task, the variables involved, and the time required to reach the target. Having a clear understanding of what things will look like better prepares you for the challenges you will invariably face.

Dieting is a skill. Most people don’t view it that way because in their minds, it’s just eating, and they have done that for the entire duration of their existence. However, the lifestyle you adapt your diet to and the methods and strategies you implement all combine to make up a rather complex system. Developing contingency plans for when you’re on vacation or at a wedding, where it’s not feasible to stick to your diet, will offer guidelines so you don’t completely fall off track. This is just one aspect of the competency component.

That being said, it’s important to move into a diet knowing you’re not going to be perfect. I recommend adopting a mindset where you set realistic goals for each diet block. Then, with subsequent blocks, the goal is to be a little better each time. This is the autonomy portion. As individuals, we need guidance, but we also need to be allowed to make mistakes and learn from the process.

In this regard, maintenance blocks are very important because the goal is to manage your diet while only measuring your weight. This develops your dieting ability because you get direct feedback through your daily weigh-ins that inform your actions moving forward. This has a high translation to free-living scenarios, where calories and macros are not as tightly controlled as you would find in a metabolic ward study.

In the end, results dictate how effective your plan was. If you failed miserably, it’s likely your plan was poorly constructed or inappropriately applied. Over time, coaches have adopted approaches that appear to produce relatively consistent and reliable results for their clients.

Research consistently shows that dietary interventions, which apply flexible control and better predict dietary success than rigid control (32). This runs contrary to the idealized fitness freak that follows their diet perfectly every day of the year. Most people have a hard time accepting that more flexibility will often produce better results long-term.

There seems to be a significant dogmatic/ideological component to this. What I mean by that is if you eat “bad foods,” you’re a bad person, and if you eat “good foods,” you’re virtuous. It sounds absurd when you read it, but this is a legitimate portrayal of a significant percentage of the population and their relationship with food.

This also goes in line with what we know about dichotomous thinking and nutrition. Identifying foods as “good” or “bad” without really applying context to the situation can often lead to disordered eating behaviour and poor weight management (33) (34).

Adopting an 80/20 rule where your diet is comprised of 80 percent whole foods and 20 percent fun foods can go a long way in increasing dietary adherence. It will also reduce some of the diet fatigue or burnout often experienced when faced with more extreme dietary measures.

TRY THIS ON FOR SIZE: Gain Weight in Your Off-Season with This Meal Plan

Keep in mind that adherence is by far the most critical factor for dietary success. A mediocre plan executed perfectly will beat a perfect plan followed poorly.

The Step-By-Step Process Covered Throughout This Article

- To find your maintenance calories, multiply your body weight in kilograms by 30-40. Follow this maintenance intake to see if you gain weight or lose weight. Remember, these equations are just there to give you a starting point; no equation is 100% accurate.

- Once your weight has stabilized increase your calories by 10-20% to create your surplus. As a beginner or intermediate, aim to gain at a rate of 0.25-0.5% of your body weight each week. Advanced athletes should aim for slower rates of weight gain. I’d recommend starting with a 10% surplus and scale accordingly if you’re not gaining at the recommended rate. This minimizes fat accumulation while maximizing muscle gained.

- Recommendations for macronutrient requirements are as follows:

Protein: 1.6-2.2g/kg of bodyweight consumed per day

Fats: 0.5-1.5g/kg of bodyweight consumed per day

Carbohydrates: at least 3-5g/kg of bodyweight consumed per day

The following are not macronutrients but are good general guidelines:

Fiber: 30-40g/day

Water: 0.7oz/pound of bodyweight - Meal timing accounts for roughly 5% of your body composition results. This is a non-negligible amount, but it’s also not a make or break scenario either. Protein feedings should be between 25-70g/meal to stimulate muscle protein synthesis and mitigate protein breakdown. Aim to consume 25g of protein immediately prior to training or within 2 hours post-workout to take advantage of increased anabolic signaling and MPS. The research shows that 3 meals are better than 1 or 2 but beyond that more meals don’t seem to have much of a beneficial effect (practical considerations aside). Adopting a meal frequency of 3 or more meals per day seems to be optimal.

- Supplements are mostly non-efficacious; however, there are some that I do recommend that seem to have a clear beneficial effect on muscle growth. Whey protein helps to increase your total protein intake throughout the day if you struggle to get it in. Although all of the mechanisms are not fully understood, it’s hypothesized that results from creatine monohydrate come from its impact on muscle protein synthesis and myogenesis (the building of muscle). The recommended dosage is 5g per day. Caffeine has ergogenic (enhancing physical performance) properties, which may decrease pain, perceived effort and increase anaerobic performance. The recommended dose for performance enhancement is 5-6 mg/kg of bodyweight taken 30 minutes prior to exercise.

- Although there are several measurement tools available, the two most practical that are available to everyone are daily bodyweight measurements and photos taken bi-weekly. Take your bodyweight naked first thing in the morning, after you go to the bathroom and before you eat or drink anything. Do this daily, and at the end of each week, take the average. The reason to use averages rather than weighing once per week is accuracy. Take your photos in the same room, ideally at the same time of day and under the same lighting. This will give you accurate feedback on your progress.

- Maintenance blocks are phases where you intentionally stall your weight to establish a new baseline, prevent muscle loss, take a break from dieting and measuring and learn to manage your weight without all of the obsessive tracking of calories and other metrics. During this time, ensure your weight does not fluctuate more than 1-3 pounds up or down from baseline. All adjustments to your diet are to be made intuitively, and daily bodyweight should still be tracked throughout the maintenance block. Maintenance phases are typically recommended to be two-thirds of the length of the diet. So if you dieted for 3 months, you would have a maintenance block of 2 months.

- Dieting to build muscle or lose fat should not run much more than 3 months at a time. Cutting cycles that follow massing and maintenance phases should aim to lose weight at a rate of 0.5-1% of your bodyweight each week. During this time, protein intake recommendations are 2.3-3.1g/kg of bodyweight consumed each day. This prevents muscle loss during a caloric deficit. Once you’ve completed one full cycle of massing, maintenance, cutting, and another maintenance phase, simply repeat the process until you’ve reached your desired bodyweight and composition.

- Adherence is the most critical aspect of successful dietary interventions. A flexible structure to your diet where you adopt a composition of 80% whole food and 20% fun food can help increase adherence and reduce diet fatigue and disordered eating behaviours. Adopting an ideological perspective on dieting where dichotomous thinking is present predicts poor weight management and disordered eating behaviours. Understanding that context matters when labeling food choices as good or bad can help mitigate this.

- Self-determination theory suggests that increasing autonomy, competence, and relatedness will improve intrinsic motivation and adherence. Understand that dieting is a skill, and it’s unlikely that you will be amazing at it from the get-go. Assume it will take time, accept that you will fail, learn from your failure, and develop your ability over time. It’s similar to the approach you would take with education. No one goes into university on their first day and expects to write their thesis. There is a lot of experience and learning that needs to take place before you become an expert. Don’t set a goal to be perfect because invariably you’re going to fail since no one is perfect. Set a goal of doing a little better each time, and watch it add up over several weeks and months until eventually you become an expert at dieting.

Now you’ve got all the tools you need to design a kick-ass muscle-building diet and get jacked. Lift big!

References

- Hall, Kevin D, et al. “Energy Balance and Its Components: Implications for Body Weight Regulation.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, American Society for Nutrition, Apr. 2012, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3302369/.

- Griffiths, Carly, et al. “Assessment of the Accuracy of Nutrient Calculations of Five Popular Nutrition Tracking Applications.” Public Health Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2018, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29534771.

- Iraki, et al. “Nutrition Recommendations for Bodybuilders in the Off-Season: A Narrative Review.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 26 June 2019, https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4663/7/7/154/htm.

- GJA, Stefan, et al. “Weight Loss, Weight Maintenance, and Adaptive Thermogenesis.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 27 Mar. 2013, https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/97/5/990/4577235.

- Carreiro, Alicia L, et al. “The Macronutrients, Appetite, and Energy Intake.” Annual Review of Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 17 July 2016, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4960974/.

- Sacks, Frank M, et al. “Comparison of Weight-Loss Diets with Different Compositions of Fat, Protein, and Carbohydrates.” The New England Journal of Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 26 Feb. 2009, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19246357/.

- M, Thomas, et al. “Higher Compared with Lower Dietary Protein during an Energy Deficit Combined with Intense Exercise Promotes Greater Lean Mass Gain and Fat Mass Loss: a Randomized Trial.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 27 Jan. 2016, https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/103/3/738/4564609.

- Murray, Bob, and Christine Rosenbloom. “Fundamentals of Glycogen Metabolism for Coaches and Athletes.” Nutrition Reviews, Oxford University Press, 1 Apr. 2018, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6019055/.

- Fleming, Jesse, et al. “Endurance Capacity and High-Intensity Exercise Performance Responses to a High Fat Diet.” International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2003, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14967870/.

- Hargreaves, Mark, et al. “Pre-Exercise Carbohydrate and Fat Ingestion: Effects on Metabolism and Performance.” Journal of Sports Sciences, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Jan. 2004, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14971431/.

- Stepto, Nigel K, et al. “Effect of Short-Term Fat Adaptation on High-Intensity Training.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Mar. 2002, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11880809.

- Pennings, Bart, et al. “Whey Protein Stimulates Postprandial Muscle Protein Accretion More Effectively than Do Casein and Casein Hydrolysate in Older Men.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 93, no. 5, Feb. 2011, pp. 997–1005., doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.008102.

- Israetel, Mike, et al. “The Renaissance Diet 2.0.” Renaissance Periodization, https://renaissanceperiodization.com/the-renaissance-diet-v2.

- Jon, Brad, and Alan Albert Aragon2. “How Much Protein Can the Body Use in a Single Meal for Muscle-Building? Implications for Daily Protein Distribution.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, BioMed Central, 27 Feb. 2018, https://jissn.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12970-018-0215-1.

- Schoenfeld, Brad Jon, et al. “Pre- versus Post-Exercise Protein Intake Has Similar Effects on Muscular Adaptations.” PeerJ, PeerJ Inc., 3 Jan. 2017, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28070459.

- Kim, Il-Young, et al. “Anabolic Response with Higher Protein Intake Is Largely Achieved through Suppression of Protein Breakdown in Older Adults.” The FASEB Journal, 1 Apr. 2017, https://www.fasebj.org/doi/abs/10.1096/fasebj.31.1_supplement.1036.2.

- Schoenfeld, Brad Jon, and Alan Albert Aragon. “Is There a Postworkout Anabolic Window of Opportunity for Nutrient Consumption? Clearing up Controversies.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, vol. 48, no. 12, 2018, pp. 911–914., doi:10.2519/jospt.2018.0615.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Military Nutrition Research. “The Energy Costs of Protein Metabolism: Lean and Mean on Uncle Sam's Team.” The Role of Protein and Amino Acids in Sustaining and Enhancing Performance., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Jan. 1999, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK224633/.

- Nunes, João Pedro, et al. “Creatine Supplementation Elicits Greater Muscle Hypertrophy in Upper than Lower Limbs and Trunk in Resistance-Trained Men.” Nutrition and Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2017, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29214923.

- Farshidfar, Farnaz, et al. “Creatine Supplementation and Skeletal Muscle Metabolism for Building Muscle Mass- Review of the Potential Mechanisms of Action.” Current Protein & Peptide Science, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2017, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28595527.

- “The Effects of Low-Dose Caffeine on Perceived Pain During a ... : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research.” LWW, https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/fulltext/2011/05000/The_Effects_of_Low_Dose_Caffeine_on_Perceived_Pain.5.aspx.

- Davis, J. K., and J. Matt Green. “Caffeine and Anaerobic Performance.” SpringerLink, Springer International Publishing, 23 Oct. 2012, https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/11317770-000000000-00000.

- “Training Practices and Ergogenic Aids Used by Male... : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research.” LWW, https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/fulltext/2013/06000/Training_Practices_and_Ergogenic_Aids_Used_by_Male.20.aspx.

- Green, J. Matt, et al. “Effects of Caffeine on Repetitions to Failure and Ratings of Perceived Exertion During Resistance Training in: International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance Volume 2 Issue 3 (2007).” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, Human Kinetics, Inc., 24 June 2019, https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/ijspp/2/3/article-p250.xml.

- “The Effect of Caffeine Ingestion on Mood State and Bench... : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research.” LWW, https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/fulltext/2011/01000/The_Effect_of_Caffeine_Ingestion_on_Mood_State_and.26.aspx.

- Wadden, Thomas A. “Long-Term Effects of Dieting on Resting Metabolic Rate in Obese Outpatients.” JAMA, American Medical Association, 8 Aug. 1990, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/382843.

- Linardon, Jake, and Sarah Mitchell. “Rigid Dietary Control, Flexible Dietary Control, and Intuitive Eating: Evidence for Their Differential Relationship to Disordered Eating and Body Image Concerns.” Eating Behaviors, Pergamon, 23 Jan. 2017, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S147101531630201X.

- Cervera, Salvador, et al. “Neuroticism and Low Self-Esteem as Risk Factors for Incident Eating Disorders in a Prospective Cohort Study.” International Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 33, no. 3, 2003, pp. 271–280., doi:10.1002/eat.10147.

- Davis, Caroline. “Normal and Neurotic Perfectionism in Eating Disorders: An Interactive Model.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 6 Dec. 1998, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199712)22:4<421::AID-EAT7>3.0.CO;2-O.

- Helms, Eric R, et al. “Evidence-Based Recommendations for Natural Bodybuilding Contest Preparation: Nutrition and Supplementation.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, BioMed Central, 12 May 2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24864135.

- “The ‘What’ and ‘Why’ of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior.” Taylor & Francis, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

- Meule, Adrian, et al. “Food Cravings Mediate the Relationship between Rigid, but Not Flexible Control of Eating Behavior and Dieting Success.” Appetite, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21824503.

- Antoniou, Evangelia E, et al. “The Mediating Role of Dichotomous Thinking and Emotional Eating in the Relationship between Depression and BMI.” Eating Behaviors, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Aug. 2017, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28135621.

- Palascha, Aikaterini, et al. “How Does Thinking in Black and White Terms Relate to Eating Behavior and Weight Regain?” Journal of Health Psychology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 2015, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25903250.

Header image credit: rawpixel © 123rf.com

Daniel DeBrocke is the chief content creator for Stacked Strength and is also a contributing writer for Breaking Muscle, Testosterone Nation, and Team Evil Genius Sports Performance. He is a strength and conditioning coach who primarily works with competitive powerlifters. As a competitive powerlifter, he holds a 1,700-pound raw total. Daniel's true passions revolve around getting people jacked and strong. In his spare time, he loves getting tattooed, long-boarding, researching, and nerding out about economics (fun trivia fact: his favourite economist is Thomas Sowell). Be sure to follow him on Instagram @stackedstrength and his Facebook page.

This was a fantastic article with great up to date supporting research. Not only was it concise but easy to digest as the reader. Thank you for taking the time to write this piece.

-Kyle