A powerlifting competition has, to a certain degree, what I like to call controlled chaos. As the conditions at the meet venue are different from where you train, there inevitably will be aspects that could throw you off a little or a lot depending on the variables.

The variables are too numerous to count, in fact. Without the meet even beginning, one can see and feel many of them. You feel the anticipation as you are waiting to weigh in the day before. There is no weigh-in when you go train at your gym. You see it, when you look at the venue and you get a twinge in your stomach from the nerves. There are no nerves when you train at your gym. You can hear it; when you are at that international meet and you hear the big and powerful Russian lifters speaking in their native tongue, trust me my friend, that can throw you off. There is no huge contingency of elite Russian lifters at your gym. You simply don’t have these variables when you go to train at your gym, but the variable are there in force at the meet. Then there is the big variable: the amount of time you have to warm up prior to the meet starting. You definitely don’t have that constraint when you go to train at your gym, ever.

Truth be told, you get to your gym to train after eating, with no weigh-in needed, no nervous stomach, no ominous European powerlifting monsters waiting for you, and you start lifting when you are darn good and ready. No one tells you when your big sets are, as they happen when they happen. Everything is different.

RECENT: Choose Your Box Squat Height Wisely

Let’s talk more about the amount of time to warm up prior to hitting your opener. Not enough warm up time prior to first attempts and you are not warmed up enough to hit your big third attempt and you might not get in your opener if you picked an aggressive opener to start off the day. Warm up too early and then you either cool down, thus risking injury perhaps missing the opener and throwing a wrench in the works for your second attempt which is of course the critical foundation for that big third attempt. Or perhaps you warm up too early and have to stay warmed up thus spending precious energy that should be conserved for the big third squat attempt. In either case, the warm-up has served to impact your performance and that is not acceptable.

The purpose of this article is to help you with a huge variable and major piece of a meet’s controlled chaos: the warm-up time allotment for the squat. This one variable can be the most stressful and not only negatively impact your total but literally make or break a meet (which I have seen happen over and over again).

For this illustration, we are going to go back in time to the beginning of this meet’s training cycle. Some of the best advice I got when I was a beginning powerlifter some 26 years ago was to compete often — not so much for the sake of setting PRs or records, but to sharpen my meet skills so that when I was ready for the big important meets, and I had already put up some big numbers, I would have some road under my belt and would be better equipped to handle any controlled chaos that might come my way, thus hopefully not letting any variables, in this case the pre-opener warm up, impede my performance when I was at that big meet. I competed a ton, sometimes making the meet just a training day. So in other words, learning about competing was (in the beginning) of greater importance than the numbers at the end of the day because, as a new lifter, the numbers are pretty much going to continue to go up if the training, technique, programming, nutrition, health and mind-set are all there.

Seminars like the Powerlifting Experience II can help lifters of all experience levels hone in on these essential keys to a successful meet.

Seminars like the Powerlifting Experience II can help lifters of all experience levels hone in on these essential keys to a successful meet.

With that said, what I did, and what you might consider doing is this: Hone in on your warm-up time, just as you hone your technique. Just like you record your max numbers on a lift in order to tweak the numbers you are going to base your training on, you are going to begin timing how long it takes you to get to what would be your first squat attempt from the time you walk into the gym. This does not mean you rush things; this means you document things.

Data is powerful. A good lifter uses data to get stronger in the gym. A great lifter uses data to use that strength successfully in a meet. There is a world of difference.

IPF World Powerlifting Champion, Dr. Rob Keyes of MGG, knows the importance of timing your warm-ups at the big international meets as well as the local level meets.

IPF World Powerlifting Champion, Dr. Rob Keyes of MGG, knows the importance of timing your warm-ups at the big international meets as well as the local level meets.

So, if you get to the gym around 8:00 AM, note about how long it takes you to get to the weight that would be the equivalent to an opener at a meet. So for example, you get there at 8 AM and by 9:30 AM, you are ready for that opener amount of weight, that is 90 minutes. From this point you are now going to cut out the non-meet items. For example, we are going to cut out that conversation you have at the gym in between sets, because at the meet, if your mind is right, you are not going to be concerned with John Doe’s bogus social media post, or where you are going to eat after the workout. You are going to need to record the amount of time it takes for you from your arrival at the gym, changing into your lifting attire and going through a thorough warm-up routine (including foam rolling, using bands to warm up, pulling the sled, whatever it is you do), the time in-between warm-ups all the way to the time you put opener weight on your back to squat. You are going to want to record that data because you will be using that amount of time the day of the meet to maximize your warm-up and pre-meet prep prior to your squat opener.

With all that said, let’s take a look at the lifter. In this case we shall call him, Dave (seems like a good powerlifter name, right?) and see how this works in practice, not just theory.

For this example, we will say that Dave is a newer lifter and lifts RAW so there are not a lot of variables like time needed to squeeze into his Metal briefs, suit, etc. Dave in this case is also a younger lifter so the jumps he makes are pretty much plate, quarter type jumps. It takes Dave about seven minutes in between warm-up jumps, and Dave always takes seven warm-ups to get to his opener. We know all of this because Dave took copious notes over the 10 week training cycle and now he has one less variable to concern himself with at the meet.

So, here is the data:

- Arrival at the gym to finishing foam roller: 12 minutes

- Number of warm-ups needed: 7

- Time needed between warm-ups: 7

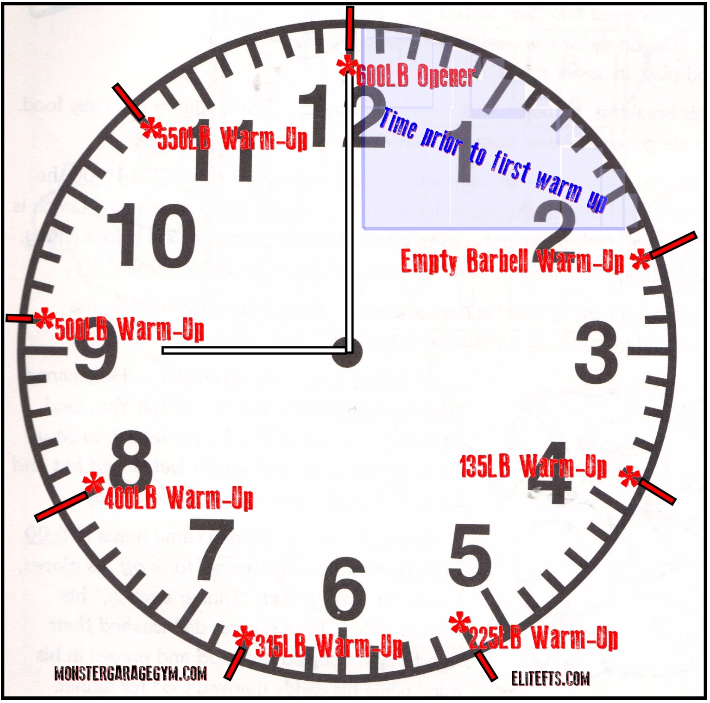

So, based on that 10 weeks of data, and since Dave rolls old school, Dave would wear a wrist watch in the warm-up area and knowing the data Dave, would know that if he is in the first flight and it starts at 9 AM, looking at his watch, he would see his watch this way:

1. Arrive by 8 AM

2. Finish his pre-barbell warm-up around 8:10 AM

3. Take his first warm-up at 8:12 AM

4. Take a subsequent, predetermined warm up every seven minutes after

- 135 pounds at 8:19 AM

- 225 pounds at 8:26 AM

- 315 pounds at 8:33 AM

- 400 pounds at 8:40 AM

- 500 pounds at 8:46 AM

- 550LBS at 8:53 AM

5. Dave is ready for his 600-pound opener as the meet starts at 9 AM

If Dave chooses to use technology, he will have this all programmed into his smart phone. I personally like the watch, as I don’t need the traffic of social media, text and the like that come with the phone to distract me when I am trying to keep up a specific pace. In either case, Dave is not guessing when should he start his pre-barbell warming up, he is not guessing when he should take his first warm-up with the barbell, and he is not guessing how much time to take in between warm-ups. Dave knows the exact times for all of these things and he just needs to stay in the moment and be mechanical with his warm-ups and know that come 9 AM, all the hard work that he has put in for this meet will not be negatively impacted by guessing at these variables.

MORE: The Gear Is Ready to Go Heavier, But Are You?

Some asides that are important to note:

- If it takes you much more than 10 minutes between warm-ups, you might want to consider some GPP, because the bigger, more important meets more often than not run very smoothly, thus very quickly. At the WPC World Powerlifting Championships in 2014, when it came to the open division, the pace was fast to begin with because it is a well organized meet, and there is a team of experienced spotter and loaders there. Throw in the fact that several lifters bombed during the squat (some for the very reason I am helping you to avoid) and the flight moved even faster. Those who were not in the best GPP shape suffered the consequences for that missing aspect of their training. This year’s IPF Worlds was like a race when it came to the master lifters. Big meets can go fast, and this whole exercise is about getting you prepared for the warm-up room variable when you get to the big meets. If you need more than 10 minutes between warm-ups, pick up an elitefts sled or prowler and get your meet GPP up to par. The lifters that are flying half way across the planet to compete are not lacking in GPP, I can guarantee you that.

- If you wear gear, you might start off with warm ups five to seven minutes apart and then might grow to 10 minutes as it takes time to get into gear, especially tight multi-ply gear. Remember, it is not the amount of time in-between the warm-ups that matters, but that you stick to the plan you have developed based on the amount of time you have allotted yourself in-between warm-ups.

- Try to get an order of lifters at your warm-up station. Either you or your handler needs to be the alpha and establish a rotation and make sure that when it is a given lifters turn, they are ready and wrapped (if wraps are allowed).

- If you are a really strong squatter, and your flight starts at 9 AM, you might take that last attempt as close to 9 AM so you don’t cool down prior to your first attempt. Conversely, if you are not the best squatter, take a good hard look at the flight board as you might be first then you should have adjusted your numbers so you are done say at 8:50 AM.

- These numbers you honed during the training cycle will, over many meets, also be further fine-tuned as you learn more and more and you grow in your meet sophistication. Nothing is written in stone and as you compete, you might realize you need a little more or a little less time prior to your opening squat.

- If at all possible, make jumps that use 25’s and 45’s. If your numbers are smaller, be sure to find the two, five, and ten-pound plates prior to your warm ups and keep them at your warm-up station, as looking for plates in the chaos of a warm-up room will take time away from your war- up clock.

- If you are NOT in the first flight, things get tricky. I would personally recommend timing the first attempts, add that time by the other two attempts in that flight, and take your predetermined warm-up clock and adjust it to that projected start time.

There will be variables you can’t control. Misloads, injuries, equipment issues, etc., might all happen as you are prepping and there is nothing you can do about that. But for the most part, meets run with very few of these issues, especially the more high profile meets. The main part is that you have accounted for a very big variable: taking the guess work out of the warm up.