If you ascribe to the works of Aristotle, you will know there are five primary senses: hearing, sight, taste, touch, and smell. As coaches, we can manipulate the frequency, magnitude, and type of input into each of these senses to attempt to ensure an optimal training environment that adequately stimulates the ability of the athlete to learn.

Having said that, unless you are running a Pavlovian-style training program, I don’t see where the taste and smell really come into play (if you do, comment and let’s talk… perhaps use of essential oils in yoga? Snacks for good reps?). Whilst we could deliver feedback through all of these sensory mediums, I am going to focus on touch in this article.

Most coaches have been in a situation where they have been training an athlete who “just can’t feel it” every time their spine turns into a pretzel on a squat, or they go hyperlordotic on an overhead press. I believe one strategy to fix this common issue (assuming there are no other underlying issues such as mobility) is through the manipulation of the balance of internal and external feedback given via touch.

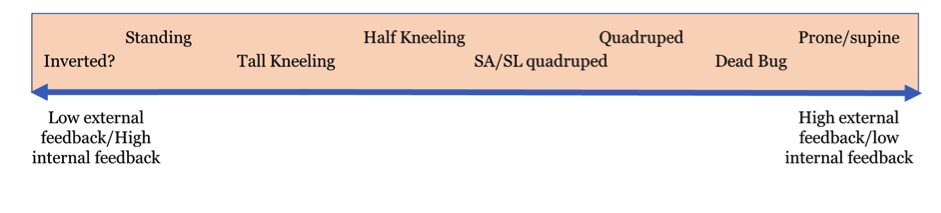

Think of internal feedback as our awareness of our body’s position in space, and external feedback as our ability to identify when, where, and how strongly we are being touched. I like to think of internal and external feedback inputs, in this context, as being inversely related. This isn’t strictly true, but generally, in positions where the athlete has a high amount of external feedback, there will be a lower reliance on internal feedback and vice versa.

Note I’ve said there is a lower reliance on internal feedback for balance, not that there is less actual internal feedback. What I would contend is important is that we utilise this inverse relationship to our advantage and look at the feedback environment of the athlete as something that can be manipulated.

One of the ways that I like to progress athletes is to move from states of high external feedback and lower internal feedback to a low external feedback, high internal feedback environment. I believe that this method of progression works well for athletes that “just can’t feel it.” The image below shows a basic model for the progression of internal and external feedback:

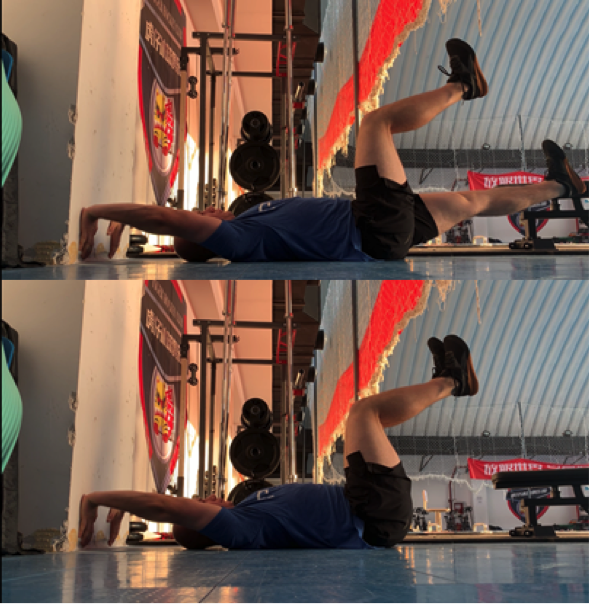

For those who are unaware of these positions, here are some pictures to provide illustration. You will note that as you move along the above model from left to right, the stability demands slowly become less and less. Furthermore, not all of these positions would necessarily be appropriate for every scenario where you may want to fix a deviant movement pattern.

What these positions do is provide a basic framework for how you can manipulate the body’s position to change the balance of internal and external feedback. One of the things I really like about the positions toward the higher external feedback conditions is that they also provide more opportunities for external cueing for the coach. For example, wherein an overhead press a coach may cue ribs down, in the dead bug position, we can now cue to press flat into the floor.

So, how do we apply the above concepts practically in the weight room? Really, this is up to the imagination of the coach. What I will present here is a basic way I have used this concept in the past to build the overhead pressing position. It’s important when you go down this track that you have confirmed it is not a mobility, injury, or strength issue that is causing the poor pressing position. If the athlete passes these basic clearances and still presents with hyperlordosis when pressing, the below may be a series of exercises to help build awareness of their position.

Exercise 1: Prone Stick Hold

With this exercise, we can not only cue good overhead position but also strengthen the scapula stabilisers responsible for holding these positions.

Cues:

- Chopsticks on your wrists.

- Stomach off the floor.

- Legs together, knees locked.

- Feel like you are being stretched.

- Create length from hand to heel.

Exercise 2: Wall Press Dead Bug

Here we are really drilling in on our trunk control when pressing overhead, specifically targeting the anterior musculature. We have the feedback from the ground so the athletes should become immediately aware when they start to go excessively lordotic. A small plate under the lower back can make a big difference to the efficacy of this exercise, as it drastically increases the amount of external feedback present.

Cues:

- Actively push away the wall.

- Squeeze into the ground.

- Maintain even pressure through the hips and lower back when moving the lower body.

Exercise 3: Wall Press Bird Dog

This is the first exercise where the trunk doesn’t have the ground to provide feedback as to the position of the spine, so now we are relying more on the athlete’s internal feedback. Whilst in the dead bug position, we were challenging the anterior trunk musculature to provide stabilisation; now we are using this bird dog variation to challenge the trunk extensors. Both are important in ensuring a strong overhead position. An added challenge here is to get your training partner to provide light perturbations to the ball whilst you try and maintain stability.

Cues:

- Push the ball into the wall.

- Create length from heel to hand.

- Neutral head.

- Neutral spine.

Exercise 4: Single-Arm Half-Kneeling Kettlebell Press

Now just for a second, imagine the Wall Ball Bird Dog with the top leg bent to at the knee and flipped 90 degrees. Voilà! We now have the Single-Arm Half-Kneeling Press. This position still has different stability demands as we are now upright, but we still have a large base of support and three points of contact with the ground. Make sure you press with the arm of the leg that is down, that way you still have to control the trunk musculature with full hip extension.

Cues:

- Roll the hips under.

- Maintain stability and balance.

- Keep your shoulders away from your ears.

Exercise 5: The Overhead Press

Congrats, you made it here. This is just a normal overhead press — what you were working to try and fix.

Cues:

- Stay neutral throughout.

- Build power through the ground. Your feet, legs, hips, and core should all be working to give stability to the system.

- Drive back through your ears.

- Keep shoulders away from your ears.

Exercise 6: Handstand

This is kind of an extra step. The point of this part of the article was about what to do if your press is lacking, and generally, I would say regressing people is the best way to go about it. But the inherent demands of the handstand are to have excellent control over the rest of your body, and the balance requirements will mean that you will get a tonne of feedback that might just help some people in sorting out their press. It is also an incredible exercise for shoulder strength and scapula stabilization. If you can hold a perfect handstand line, I think your overhead press might be A-OK.

Disclaimer: I’m not a handstand guru. Go and see someone that is if this paragraph lit some curiosity inside of you.

Cues:

- Spread your hands and grip the ground.

- Create length from hands to toes.

- Maintain a neutral spine.

This article has given you a model for how to manipulate the sense of touch to create an altered feedback environment for your athlete. How you use the interaction between internal and external feedback will be based on how you have assessed the athlete and what you feel their needs are.

Hopefully, I’ve stimulated you to think about things outside of improving mobility and strength when trying to create an optimal environment to improve an athlete’s technique.

I’d love some questions, so if you have any, feel free to shoot them through below.

Key Points:

- Positions whereby the athlete has a high amount of external feedback, there will be a lower reliance on internal feedback and vice versa.

- By manipulating the feedback constraints of an exercise, you can change the learning environment for an athlete.

- Consider how exercise variations can create external cueing options for the coach.

References

- McGill, SM. (2015) Low back disorders: evidence-based prevention and rehabilitation: Human Kinetics.

- McGlone F., Wessberg J., and Olausson H. (2014) Discriminative and Affective Touch: Sensing and Feeling. Neuron 82: 737-755.

Disclaimer

Any advice given here is general in nature. It should not be taken out of context, and any individual wishing to apply any of the advice should seek a fitness professional to assess their individual situation. If you forego this advice, you could be doing yourself more harm than good.

Charles Dudley is a performance coach based out of Beijing, China, and is working for the Chinese Olympic Committee. He has previously worked privately as a strength and conditioning coach for a number of sports, such as rugby union, tennis, and hockey, in addition to coaching a number of national-level weightlifters. Charles has also been a tactical coach in rugby union and rugby 7s at the schoolboy and academy/elite pathway levels.

1 Comment