Due to the tremendous amount of information available in regards to strength training, it may be difficult to determine which system works best for competitive bench pressing. There are various magazines, peer-reviewed journals, and textbooks available to the reader or athlete. There are many factors involved in the training of a competitive bench presser. Choosing a system that addresses all of these needs can be an arduous task. Textbooks in America exclusively present the Western Periodization model while the Eastern European textbooks present a non-linear type periodization, also termed the conjugate method. This literature review will delve into previous literature to surmise which system would be best for the competitive bench presser. Introduction Determining the most effective and efficient method of strength development has been a primary focus of strength coaches and strength researchers for decades (13). Sorting through the numerous models, theories, and studies is a difficult yet very important part of being able to prescribe the most appropriate training regimen for an athlete. In the case of the competitive powerlifter, a major goal is to attain a peak physical performance at a particular point in time, such as for a major competition (8). It is the intent of this literature review to present previous research regarding resistance training methods for increasing strength as they apply to bench pressing for the competitive powerlifter. This literature review will examine linear periodization, non-linear periodization, and conjugate method periodization. Summary of Selected Literature

Due to the tremendous amount of information available in regards to strength training, it may be difficult to determine which system works best for competitive bench pressing. There are various magazines, peer-reviewed journals, and textbooks available to the reader or athlete. There are many factors involved in the training of a competitive bench presser. Choosing a system that addresses all of these needs can be an arduous task. Textbooks in America exclusively present the Western Periodization model while the Eastern European textbooks present a non-linear type periodization, also termed the conjugate method. This literature review will delve into previous literature to surmise which system would be best for the competitive bench presser. Introduction Determining the most effective and efficient method of strength development has been a primary focus of strength coaches and strength researchers for decades (13). Sorting through the numerous models, theories, and studies is a difficult yet very important part of being able to prescribe the most appropriate training regimen for an athlete. In the case of the competitive powerlifter, a major goal is to attain a peak physical performance at a particular point in time, such as for a major competition (8). It is the intent of this literature review to present previous research regarding resistance training methods for increasing strength as they apply to bench pressing for the competitive powerlifter. This literature review will examine linear periodization, non-linear periodization, and conjugate method periodization. Summary of Selected Literature Periodization

Periodization can be defined as a logical, phasic method of adjusting training variables in order to increase the potential for achieving specific performance goals (19). A periodized regimen structures the training program into phases in order to maximize an athlete’s capacity to meet the specifics of strength according to the needs of his or her sport (5). Studies of periodized programs to date have investigated resistance training techniques and the variables that can be manipulated to optimize performance. These variables include the number of sets performed of each exercise, the number of repetitions per set, the number of exercises performed per training session, the length of rest periods between sets and exercises, the resistance used for a set, and the type of muscle action emphasized (e.g. eccentric, concentric, isometric). The number of training sessions per day and per week is also included with these variables (8). The effectiveness of a periodized program results from the systematic variation of these variables, allowing the athlete adequate recovery in activity levels, volume of exercise, and loading (12). Volume and Intensity Total volume is important to calculate when designing a strength training program. An excessive amount of volume may lead to an overtrained state, which is defined by a decrease in performance (9). An undertrained state, occurring from volume that is low in relation to the level of fitness of the lifter, may also result in a decrease in performance due to not enough work being done (12). Intensity is defined as the greatest amount of weight that a subject can perform for one repetition maximum. The relationship between volume and intensity is crucial when planning a program so that training is most effective and least injurious for the athlete (15). It is also important to consider that many previous resistance training studies have failed to equate training volume and intensity between subject groups. While attempting to compare training protocols that are different in sets, repetitions, resistance, frequency, and duration, it is difficult to accurately equate training volume. Failure to do so makes it impossible for researchers to attribute differences in strength gains to the program design or differences in volume or intensity between groups (13). In a study conducted by Baker, short-term training using previously trained subjects showed no differences in maximal strength when volume and intensity were equated (3). In contrast, other researchers state that equating volume might initially sound logical, but it is important to realize that the periodized model might owe its efficacy to the high overall volume made possible by the variations in volume and intensity. In other words, the training volume should be treated as a study factor and not as a confounding factor (4). It is obvious that researchers have not reached an agreement on the parameters that should be used to equate volume and intensity. Linear Periodization The traditional periodization model is commonly referred to as linear periodization because of the gradual increases in training intensity and decreases in training volume over time. These changes are typically made approximately every four weeks. The NSCA basic guidelines for linear periodized programs include the phases of preparation, hypertrophy, strength, power, competition, and active rest (12). A linear periodized program outlined by Bompa includes the phases of anatomical adaptation, maximum strength, conversion, maintenance, cessation, and regeneration (5). Fleck and Kraemer characterize linear periodization training to include the phases of hypertrophy, strength and power, peaking, and active rest (7). Although different terminology is used in the literature in describing the phases of training, all three programs incorporate the same elements in variant order. According to Fleck and Kraemer, training for the competitive powerlifter will begin eight weeks prior to a competition. The first phase of this system is devoted to hypertrophy. Fleck and Kraemer state that hypertrophy, which is characterized by high volume, low resistance exercise, is implemented to help the lifter adapt to resistance training and cause an increase in muscle mass (7). The goal of the strength/power phase is to develop maximum strength to the highest level of the athlete’s capacity. The peak phase, also referred to as the competition phase, is used to increase peak strength and power for a particular competition. The active rest phase, also referred to as the regeneration phase, completes the cycle of training with the purpose of rehabilitating and restoring the athlete both physically and psychologically (5, 7, 12). Non-Linear Periodization  Non-linear periodization, also referred to as undulating periodization, differs from linear periodization by making changes in intensity and volume on a more frequent basis, typically weekly or bi-weekly. Daily undulating periodization is also a non-linear system with alterations in training volume and intensity made on a daily basis (14). The NSCA non-linear model consists of a light day, power day, active rest, moderate day, and heavy day (12). The light day consists of two to four sets of an exercise performed for ten to fifteen repetitions, with one to two minutes rest between sets. On the power day, the lifter handles a load that is thirty to sixty percent of his one repetition maximum, with the focus on moving the bar at a high velocity. The power day may also include the performance of plyometric exercise because of its explosive nature. This is defined as a quick powerful movement using a pre-stretch or countermovement. The active rest day does not consist of specific exercises but rather any restorative movements the lifter chooses to lightly work the same muscle groups used on the previous day. On the moderate day, the lifter trains two to four sets of an exercise with a load that is five to ten percent lower than the load used for his heavy day. Heavy day follows the moderate day with three to four sets of an exercise performed with a load that allows only three to six repetitions. A one to two minute rest period betweensets is recommended. There are two additional days of active rest following the heavy day (12). Comparison of Linear and Non-Linear Periodization Models A study comparing linear periodization to daily undulating periodization for strength increases resulted in strength enhancements for both groups, although the absolute increases for bench press did not reach statistical significance at any time (13). This may have been due in part to the fact that the bench press involves the use of smaller muscle groups therefore making significant differences more difficult to achieve (22). Another study comparing the effects of three weight training programs using partially equated volumes resulted in the group that incorporated more variation in their training program eliciting greater strength gains (22). Kraemer compared an undulating model to a single-set protocol and found that one repetition maximum strength rose in the undulating group whereas the single set group displayed an early plateau (10). Non-linear periodization has proven to be as effective as classic periodization protocols in short-term studies and superior to non-periodized training methods over longer training periods (3). Deviations of the non-linear program include alternating cycles every two to three weeks and incorporating adaptability to the program design to meet the needs of various athletes. The non-linear program can be adjusted in whatever manner yields the best results for the lifter (12). This type of program sets the foundation for the conjugate method of training. Conjugate Method of Training The conjugate method of training involves the concurrent training of several motor skills or a wide multilateral skill development approach (11). Siff and Verkhoshansky describe the importance of such training when they discuss the contents of special strength training. This training should be multifaceted and include specific stimuli to produce the strength fitness required for the given sport based upon the athlete’s level of sports mastery. Therefore, the conjugate method of training maintains the advantages of the cumulative results of training as well as the accentuation of the specific training effect of the loading of a given training objective. This results in a higher level of work capacity and training fitness for the lifter (15). Verkhoshansky states that the positive accumulation of these training effects results in a more unidirectional elevation of the body to a higher and more stable work capacity (21). The conjugate system uses Prilipen’s recommendations (table 1) to regulate volume for the components of the training days (1).

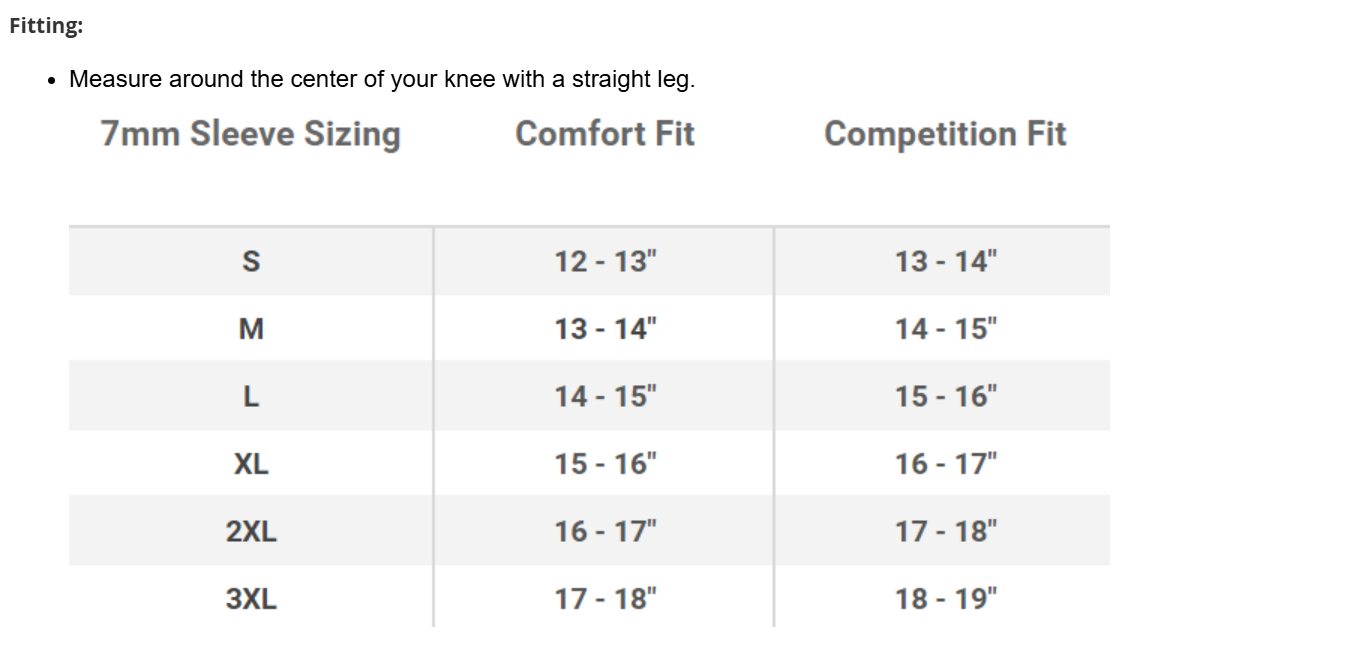

Non-linear periodization, also referred to as undulating periodization, differs from linear periodization by making changes in intensity and volume on a more frequent basis, typically weekly or bi-weekly. Daily undulating periodization is also a non-linear system with alterations in training volume and intensity made on a daily basis (14). The NSCA non-linear model consists of a light day, power day, active rest, moderate day, and heavy day (12). The light day consists of two to four sets of an exercise performed for ten to fifteen repetitions, with one to two minutes rest between sets. On the power day, the lifter handles a load that is thirty to sixty percent of his one repetition maximum, with the focus on moving the bar at a high velocity. The power day may also include the performance of plyometric exercise because of its explosive nature. This is defined as a quick powerful movement using a pre-stretch or countermovement. The active rest day does not consist of specific exercises but rather any restorative movements the lifter chooses to lightly work the same muscle groups used on the previous day. On the moderate day, the lifter trains two to four sets of an exercise with a load that is five to ten percent lower than the load used for his heavy day. Heavy day follows the moderate day with three to four sets of an exercise performed with a load that allows only three to six repetitions. A one to two minute rest period betweensets is recommended. There are two additional days of active rest following the heavy day (12). Comparison of Linear and Non-Linear Periodization Models A study comparing linear periodization to daily undulating periodization for strength increases resulted in strength enhancements for both groups, although the absolute increases for bench press did not reach statistical significance at any time (13). This may have been due in part to the fact that the bench press involves the use of smaller muscle groups therefore making significant differences more difficult to achieve (22). Another study comparing the effects of three weight training programs using partially equated volumes resulted in the group that incorporated more variation in their training program eliciting greater strength gains (22). Kraemer compared an undulating model to a single-set protocol and found that one repetition maximum strength rose in the undulating group whereas the single set group displayed an early plateau (10). Non-linear periodization has proven to be as effective as classic periodization protocols in short-term studies and superior to non-periodized training methods over longer training periods (3). Deviations of the non-linear program include alternating cycles every two to three weeks and incorporating adaptability to the program design to meet the needs of various athletes. The non-linear program can be adjusted in whatever manner yields the best results for the lifter (12). This type of program sets the foundation for the conjugate method of training. Conjugate Method of Training The conjugate method of training involves the concurrent training of several motor skills or a wide multilateral skill development approach (11). Siff and Verkhoshansky describe the importance of such training when they discuss the contents of special strength training. This training should be multifaceted and include specific stimuli to produce the strength fitness required for the given sport based upon the athlete’s level of sports mastery. Therefore, the conjugate method of training maintains the advantages of the cumulative results of training as well as the accentuation of the specific training effect of the loading of a given training objective. This results in a higher level of work capacity and training fitness for the lifter (15). Verkhoshansky states that the positive accumulation of these training effects results in a more unidirectional elevation of the body to a higher and more stable work capacity (21). The conjugate system uses Prilipen’s recommendations (table 1) to regulate volume for the components of the training days (1). Table 1. Prilipin’s table; number of reps for percent training

| Percent of one rep max | Repetitions per set | Optimal total | Range |

| 55–65 | 3–6 | 24 | 18–30 |

| 70–75 | 3–6 | 18 | 12–24 |

| 80–85 | 2–4 | 15 | 10–20 |

| Above 90 | 1–2 | 7 | 4–10 |

The force-velocity curve is an important factor in maximum effort training because as a body part gains more leverage, less force is required to move the bar to the completion of the lift (2). This is deceleration, a result of peak contraction. The peak contraction principle focuses on increasing muscle strength primarily at the weakest point of the curve. The force-velocity curve is affected by joint angular velocity. Peak contraction will occur when the external resistance is maximal and where muscular strength exertion is minimal. Zatsiorsky proposes accommodating resistance as a means of overcoming the force-velocity curve (23). Accommodating Resistance Zatsiorsky defines accommodating resistance as using special means to accommodate resistance through an entire range of motion rather than at a specific point. Simmons added the use of bands and chains to the conjugate method of training in order to address the need to accommodate resistance (16). The implementation of chains accomplishes this because as the bar is lifted, more links of the chain come off the floor and increase the load. This requires the lifter to push harder in order to keep the bar moving. The implementation of bands accomplishes this because as the bar is lifted, the bands increase the downward tension, resulting in the lifter needing to push harder to keep the bar accelerating. Training with bands and chains is a form of eccentric overloading that trains the athlete to alter the force velocity curve. Externally altering the force velocity curve is important because it allows the athlete to increase eccentric velocity due to a decrease in concentric force production. This type of training is referred to by Siff as hybrid training (15). The bands and chains are used to increase eccentric bar velocity, which in turn decreases the amount of force needed to finish a particular lift. The added downward velocity increases kinetic energy, a property of speed (18). In a study by Burke, it was hypothesized that fast bar lowering coupled with fast bar acceleration would provide additional force due to the theory of elastic energy storage, also called kinetic energy (6). Training the Competitive Bench Press The training program for a powerlifting athlete incorporates a periodized system for developing the ability to perform at a peak level with the goal to achieve a one repetition maximum (1RM) lift in the competitive arena. Simmons examined the writings of several European researchers including Ajan and Boroga, Bompa, Siff, Verkhoshansky, and Zatsiorsky. These authors gathered their data from the training logs of elite level strength athletes as the subject groups. This research concluded that there are sport specific strengths that the powerlifter needs to develop. These include speed strength for the ability to move the barbell at a high velocity, acceleration strength for the ability to move the barbell to lockout, concentric strength for the pushing of the barbell, eccentric strength for the lowering of a barbell, and static strength for holding a barbell in a locked position (17, 21). Simmons incorporated these qualities of speed, acceleration, concentric, eccentric, and static strength into the athlete’s cycle so that gains could be made continuously throughout the year with no off-season. This allows the athlete to remain in a highly trained state so that he/she is always prepared for a competition (17). Future Research A primary concern of some of the studies reviewed is the frequent use of untrained or minimally trained subjects as a measure for comparing resistance training protocols (8, 20, 3). The gains these athletes achieved may have been due to the initial adaptation that occurs when the body is responding to increased neuromuscular demands (13, 9). Therefore, the strength improvements may not be directly attributed to the training programs of the study but rather to Selyes general adaptation syndrome. This syndrome is defined as the body’s response to an acute bout of exercise (13, 9). Once the body has adapted to the demand or load, strength increases wane. However, that raises a second concern—that the studies were not carried out for long enough periods of time (9, 8). A study that is of short duration will not be long enough to indicate the onset of a plateaued state. Furthermore, these short-term results would not necessarily be applicable to long-term athletic training (8). A final problem with the studies reviewed is their applicability to the sport of competitive bench pressing. Journal research of resistance training protocols for this population of athletes was minimal at best. Therefore, the relationship of other peer-reviewed literature to this literature review is informational but not always specifically or directly comparable. It would be of great value to see further long-term research in this area, particularly with highly trained bench pressing athletes in studies designed to compare various protocols directly with the conjugate method. Conclusion

The force-velocity curve is an important factor in maximum effort training because as a body part gains more leverage, less force is required to move the bar to the completion of the lift (2). This is deceleration, a result of peak contraction. The peak contraction principle focuses on increasing muscle strength primarily at the weakest point of the curve. The force-velocity curve is affected by joint angular velocity. Peak contraction will occur when the external resistance is maximal and where muscular strength exertion is minimal. Zatsiorsky proposes accommodating resistance as a means of overcoming the force-velocity curve (23). Accommodating Resistance Zatsiorsky defines accommodating resistance as using special means to accommodate resistance through an entire range of motion rather than at a specific point. Simmons added the use of bands and chains to the conjugate method of training in order to address the need to accommodate resistance (16). The implementation of chains accomplishes this because as the bar is lifted, more links of the chain come off the floor and increase the load. This requires the lifter to push harder in order to keep the bar moving. The implementation of bands accomplishes this because as the bar is lifted, the bands increase the downward tension, resulting in the lifter needing to push harder to keep the bar accelerating. Training with bands and chains is a form of eccentric overloading that trains the athlete to alter the force velocity curve. Externally altering the force velocity curve is important because it allows the athlete to increase eccentric velocity due to a decrease in concentric force production. This type of training is referred to by Siff as hybrid training (15). The bands and chains are used to increase eccentric bar velocity, which in turn decreases the amount of force needed to finish a particular lift. The added downward velocity increases kinetic energy, a property of speed (18). In a study by Burke, it was hypothesized that fast bar lowering coupled with fast bar acceleration would provide additional force due to the theory of elastic energy storage, also called kinetic energy (6). Training the Competitive Bench Press The training program for a powerlifting athlete incorporates a periodized system for developing the ability to perform at a peak level with the goal to achieve a one repetition maximum (1RM) lift in the competitive arena. Simmons examined the writings of several European researchers including Ajan and Boroga, Bompa, Siff, Verkhoshansky, and Zatsiorsky. These authors gathered their data from the training logs of elite level strength athletes as the subject groups. This research concluded that there are sport specific strengths that the powerlifter needs to develop. These include speed strength for the ability to move the barbell at a high velocity, acceleration strength for the ability to move the barbell to lockout, concentric strength for the pushing of the barbell, eccentric strength for the lowering of a barbell, and static strength for holding a barbell in a locked position (17, 21). Simmons incorporated these qualities of speed, acceleration, concentric, eccentric, and static strength into the athlete’s cycle so that gains could be made continuously throughout the year with no off-season. This allows the athlete to remain in a highly trained state so that he/she is always prepared for a competition (17). Future Research A primary concern of some of the studies reviewed is the frequent use of untrained or minimally trained subjects as a measure for comparing resistance training protocols (8, 20, 3). The gains these athletes achieved may have been due to the initial adaptation that occurs when the body is responding to increased neuromuscular demands (13, 9). Therefore, the strength improvements may not be directly attributed to the training programs of the study but rather to Selyes general adaptation syndrome. This syndrome is defined as the body’s response to an acute bout of exercise (13, 9). Once the body has adapted to the demand or load, strength increases wane. However, that raises a second concern—that the studies were not carried out for long enough periods of time (9, 8). A study that is of short duration will not be long enough to indicate the onset of a plateaued state. Furthermore, these short-term results would not necessarily be applicable to long-term athletic training (8). A final problem with the studies reviewed is their applicability to the sport of competitive bench pressing. Journal research of resistance training protocols for this population of athletes was minimal at best. Therefore, the relationship of other peer-reviewed literature to this literature review is informational but not always specifically or directly comparable. It would be of great value to see further long-term research in this area, particularly with highly trained bench pressing athletes in studies designed to compare various protocols directly with the conjugate method. Conclusion  There is much literature available on the subject of strength training protocols. Each method is supported by research indicating that it will prove successful in enhancing the athlete’s performance. Therefore, selecting a strength training program with the goal of increasing maximum bench pressing ability is a complex and confusing decision. It would take many years to physically try each of the systems that have been investigated due to the long-term commitment required to actually determine the effectiveness of a program. Most athletes do not have the time or desire to do this due to the “down time” of training spent learning a new system while still remaining in the competitive arena. In this literature review, two distinctly different methods of training were analyzed. With so many variations of resistance training protocols studied, published, and practiced, the question remains as to which system will yield the greatest strength gains. References 1. Ajan T and Baroga L (1988) Weightlifting Fitness For All Sports. Budapest, Hungary, pg 162. 2. Baechle TR and Earle R (2000) Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, Second edition. Champaign, IL, pg 10. 3. Baker D, Wilson G, Carlyon R (1994) Periodization: the effect on strength of manipulating volume and intensity. J. of Strength Cond. Research. 8(4):235-236,241. 4. Benedict T (1999) Manipulating resistance training program variables to optimize maximum strength in men: a review. J. of Strength Cond. Research. 13(3):297. 5. Bompa T (1994) Theory and Methodology of Training, Third edition. Dubuque, IA, pgs 177, 179, 375. 6. Burke DG (1999) The influence of varied resistance and speed of concentric antagonistic contractions on subsequent concentric agonistic efforts. J. Strength Cond. Research. 13(3):196. 7. Fleck SJ and Kramer WJ (1997) Designing Resistance Training Programs, Second edition. Champaign, IL, pg 103, 238. 8.Fleck SJ (1999) Periodized strength training: a critical review. J. Strength Cond. Research, 13(1): 82-84, 86. 9. Fry AC, Webber JM, Weiss LW, Fry MD, and Li Y (2000) Impaired performances with excessive high-intensity free-weight training. J. Strength Cond. Research. 14(1):54-55, 58. 10. Kraemer WJ (1997) A series of studies: the physiological basis for strength training in American football: fact over philosophy. J. Strength Cond. Research. 11:131-142. 1997. In: Benedict T (1999) Manipulating resistance training program variables to optimize maximum strength in men: a review. J. Strength Cond. Research. 13(3):289-304. 11. Myslinski T, The Development of The Russian Conjugate Sequence System https://www.elitefts.com, pg 2. 12. Pearson D, Faigenbaum A, Conley M, Kraemer WJ (2000) The national strength and conditioning association’s basic guidelines for the resistance training of athletes. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 22(4): 16,18,19. 13. Rhea MR, Ball SD, Phillips WT, Burkett LN (2002) A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for strength. J. Strength Cond. Research, 16(2): 250-252. 14. Rhea, MR, Phillips WT, Burkett LN, Stone WJ, Ball SD, Alvar BA, Thomas AB (2003) A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for local muscular endurance. J. Strength Cond. Research, 17(1):83 15. Siff MC (2000) Supertraining, fifth ed. Denver, CO, pgs 204, 330-32, 371, 397. 16. Simmons Louie (2001) Eccentric and concentric training. Powerlifting USA,24(6):22-23. 17. Simmons Louie (2001) Special strengths. Powerlifting USA, 24(7):35. 18. Simmons Louie (2003) Virtual force. Powerlifting USA, 26(10):13-15. 19. Stone MH, O’Bryant HS, Haff GG, Koch AJ, Schilling BK, Johnson RL, Stone ME (1999) Periodization: Effects of manipulating volume and intensity (part 1) J. Strength Cond. Res. 21(2):56-62. In: Stone MH, Potteiger JA, Pierce KC, Proulx CM, O’Bryant HS, Johnson RL, Stone ME (2000) Comparison of the effects of three different weight-training programs on the one repetition maximum squat. J. Strength Cond. Res. 14(3): 332-337. 20. Stone MH, Potteiger JA, Pierce KC, Proulx CM, O’Bryant HS, Johnson RL, Stone ME (2000) Comparison of the effects of three different weight-training programs on the one repetition maximum squat. J. Strength Cond. Res. 14(3): 333. 21. Verkhoshansky YV (1986) Fundamentals of Special Strength Training in Sport. Livonia, MI, pg 39. 22. Willoughby DS (1993) The effects of mesocycle-length weight training programs involving periodization and partially equated volumes on upper and lower body strength. J. Strength Cond. Research. 7(1):3,5,7. 23. Zatsiorsky VM (1995) Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL, pgs 57, 149.

There is much literature available on the subject of strength training protocols. Each method is supported by research indicating that it will prove successful in enhancing the athlete’s performance. Therefore, selecting a strength training program with the goal of increasing maximum bench pressing ability is a complex and confusing decision. It would take many years to physically try each of the systems that have been investigated due to the long-term commitment required to actually determine the effectiveness of a program. Most athletes do not have the time or desire to do this due to the “down time” of training spent learning a new system while still remaining in the competitive arena. In this literature review, two distinctly different methods of training were analyzed. With so many variations of resistance training protocols studied, published, and practiced, the question remains as to which system will yield the greatest strength gains. References 1. Ajan T and Baroga L (1988) Weightlifting Fitness For All Sports. Budapest, Hungary, pg 162. 2. Baechle TR and Earle R (2000) Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, Second edition. Champaign, IL, pg 10. 3. Baker D, Wilson G, Carlyon R (1994) Periodization: the effect on strength of manipulating volume and intensity. J. of Strength Cond. Research. 8(4):235-236,241. 4. Benedict T (1999) Manipulating resistance training program variables to optimize maximum strength in men: a review. J. of Strength Cond. Research. 13(3):297. 5. Bompa T (1994) Theory and Methodology of Training, Third edition. Dubuque, IA, pgs 177, 179, 375. 6. Burke DG (1999) The influence of varied resistance and speed of concentric antagonistic contractions on subsequent concentric agonistic efforts. J. Strength Cond. Research. 13(3):196. 7. Fleck SJ and Kramer WJ (1997) Designing Resistance Training Programs, Second edition. Champaign, IL, pg 103, 238. 8.Fleck SJ (1999) Periodized strength training: a critical review. J. Strength Cond. Research, 13(1): 82-84, 86. 9. Fry AC, Webber JM, Weiss LW, Fry MD, and Li Y (2000) Impaired performances with excessive high-intensity free-weight training. J. Strength Cond. Research. 14(1):54-55, 58. 10. Kraemer WJ (1997) A series of studies: the physiological basis for strength training in American football: fact over philosophy. J. Strength Cond. Research. 11:131-142. 1997. In: Benedict T (1999) Manipulating resistance training program variables to optimize maximum strength in men: a review. J. Strength Cond. Research. 13(3):289-304. 11. Myslinski T, The Development of The Russian Conjugate Sequence System https://www.elitefts.com, pg 2. 12. Pearson D, Faigenbaum A, Conley M, Kraemer WJ (2000) The national strength and conditioning association’s basic guidelines for the resistance training of athletes. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 22(4): 16,18,19. 13. Rhea MR, Ball SD, Phillips WT, Burkett LN (2002) A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for strength. J. Strength Cond. Research, 16(2): 250-252. 14. Rhea, MR, Phillips WT, Burkett LN, Stone WJ, Ball SD, Alvar BA, Thomas AB (2003) A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for local muscular endurance. J. Strength Cond. Research, 17(1):83 15. Siff MC (2000) Supertraining, fifth ed. Denver, CO, pgs 204, 330-32, 371, 397. 16. Simmons Louie (2001) Eccentric and concentric training. Powerlifting USA,24(6):22-23. 17. Simmons Louie (2001) Special strengths. Powerlifting USA, 24(7):35. 18. Simmons Louie (2003) Virtual force. Powerlifting USA, 26(10):13-15. 19. Stone MH, O’Bryant HS, Haff GG, Koch AJ, Schilling BK, Johnson RL, Stone ME (1999) Periodization: Effects of manipulating volume and intensity (part 1) J. Strength Cond. Res. 21(2):56-62. In: Stone MH, Potteiger JA, Pierce KC, Proulx CM, O’Bryant HS, Johnson RL, Stone ME (2000) Comparison of the effects of three different weight-training programs on the one repetition maximum squat. J. Strength Cond. Res. 14(3): 332-337. 20. Stone MH, Potteiger JA, Pierce KC, Proulx CM, O’Bryant HS, Johnson RL, Stone ME (2000) Comparison of the effects of three different weight-training programs on the one repetition maximum squat. J. Strength Cond. Res. 14(3): 333. 21. Verkhoshansky YV (1986) Fundamentals of Special Strength Training in Sport. Livonia, MI, pg 39. 22. Willoughby DS (1993) The effects of mesocycle-length weight training programs involving periodization and partially equated volumes on upper and lower body strength. J. Strength Cond. Research. 7(1):3,5,7. 23. Zatsiorsky VM (1995) Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL, pgs 57, 149.