elitefts™ Sunday Edition So often we get caught up in achieving a goal that we tend to overlook the obvious when problems arise. Personally, I know that I’ve been guilty of watching videos of my lifts and picking them apart to oblivion. However, to pinpoint our weaknesses, we’re often told to look at where our technique breaks down—sometimes it can be a strength issue, but sometimes it’s not. I’ve watched numerous videos of myself and of other lifters/athletes over the years, and some of the simplest cues you hear being yelled actually give us insight to a much bigger issue. "Get tight...Knees out...Breathe into your belt...Shoulder blades down and together...Break the bar!" These cues are all really indicating a lack of one thing: Stability.

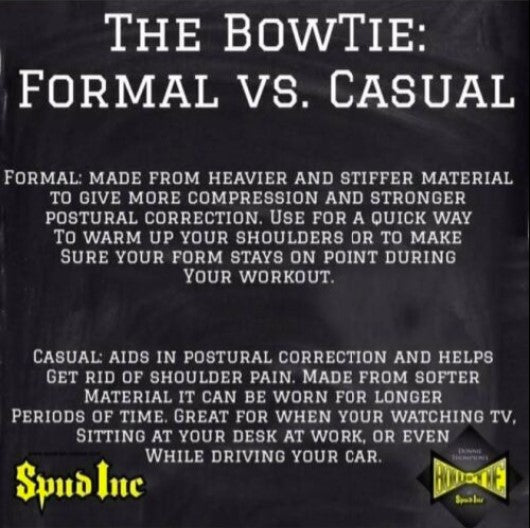

I often hear people talk about thoracic extension, hip range of motion, glute strength, etc. These problems seem to start at the body’s center and work their way outward. Let’s think about it: if your hips lack mobility, is this because you really lack range of motion? Or could it just be your body's built-in defense mechanism to prevent further damage or injury? That achy shoulder—is it because you need more direct rotator cuff work, or is your upper trap not allowing your lower trap to put your scapula in a position that allows you to better stabilize the joint? Most of us don’t even breathe properly, so do we deserve to do all of these other complicated things? I would argue and say that we need to take a step back. Before doing the single-leg-walking-overhead-twisting-leg-lift-with-a-reach, we need to look at something a little simpler that may get us faster results. Let’s look at the cues from before:- Get tight: a global cue that signals you to activate your musculature in order to make your body more rigid under load.

- Knees out: a cue to engage your hip abductors, which will help stabilize the hip and keep your knees from caving in. Essentially, you are stabilizing the lower half of the body.

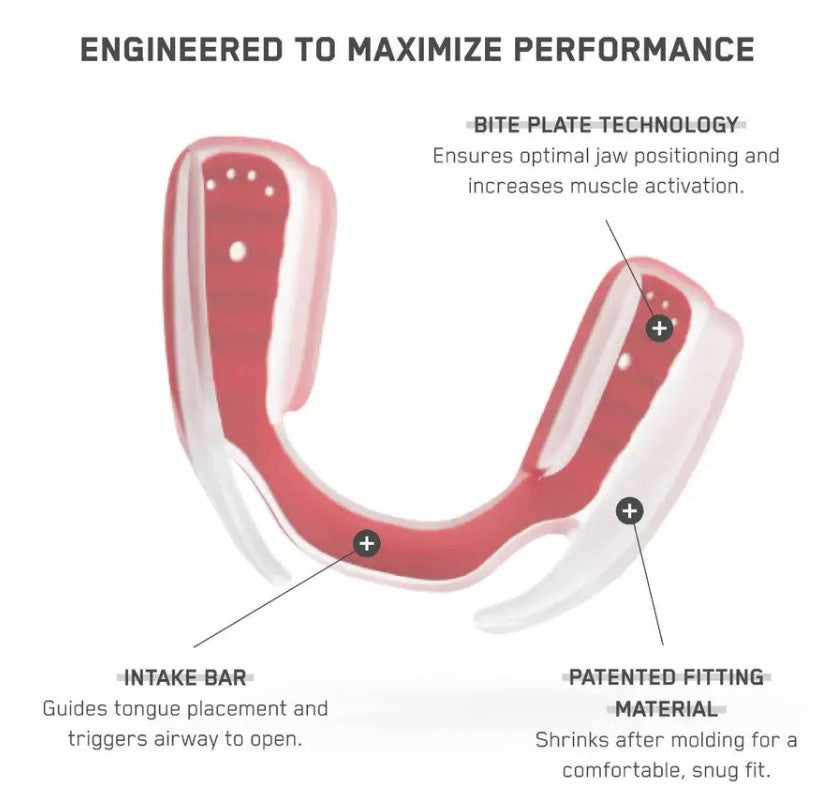

- Breathe into your belt: this should imply taking a big diaphragmatic breath—the ultimate stabilizer—by allowing you to activate your deep abdominal muscles. This helps eliminate the need for muscles like the scalenes, upper trap, and pec minor to aid in breathing and work instead to stabilize other joints.

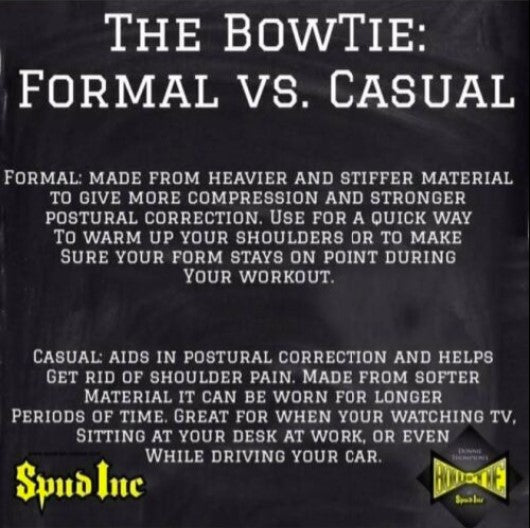

- Shoulder blades down and together: retraction and depression of the shoulder blades allows the rotator cuff to do its job and keep the glenohumeral head centered in the fossa. Using this technique allows the shoulder joint to be actively stabilized throughout its range of motion.

- Break the bar: this cue that reminds you to externally rotate the hands also activates musculature in the rotator cuff, giving you a much more stable platform from which to press.