Strength-speed and speed-strength are common misconceptions that I hopefully shed some light on a while back with my article on that topic. Another common misconception is over the term “starting strength.” I’m not sure where this error arose. Was it from Mark Rippetoe’s book of the same name? Was it something that was lost in translation?

Most are under the impression that starting strength is anything that you’re doing from a dead stop. Many lifters do deadlifts to build starting strength or bench press with the bar lying on the pins. What does this actually build? Pure concentric only absolute strength. Lifters feel that it does develop something differently than the other exercises—and it does. There isn't any eccentric to increase muscle damage. A lifter is moving a heavy load very slowly (because there isn't any neurophysiological mechanism such as the stretch reflex to help out here). Is this a bad thing to develop? No. It’s a great thing to develop, especially if that’s what you want to develop. Unfortunately, some of the lifters who read the translated Soviet texts got their thoughts jumbled up and they started doing these things to develop starting strength, which didn’t develop at all. Instead, they developed something entirely different.

So what is starting strength then? I’m glad you asked. Starting strength is simply the ability to start from a dead stop and overcome your inertia as rapidly as possible. One example is a receiver out on the edge who hopes to blow by the defensive back covering him on the line. Instead of making contact, he relies on that “fast first step” to try and beat his opponent.

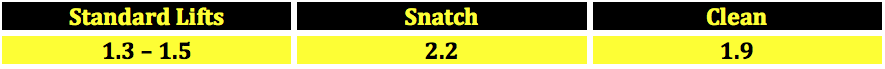

According to Dr. Anatoly Bondarchuk, starting strength is the ability to overcome inertia directly into high velocities (1). So essentially, if we were to look at a transfer of training, this would be practicing light exercises at super high velocities. If you've seen my presentation from the 2014 NSCA Coaches' Conference, I had mentioned that starting strength occurred in standard lifts at 1.3–1.5 meters/second and higher (depends on the amplitude of motion), and on the Olympic lifts, we’re probably looking at about 2.2 meters/second for a snatch or about 1.9 meters/second for a clean. (To be completely honest, those are guesses. I haven't ran any data on this, but that is my gut instinct as to what the velocities should be.)

Before moving along, I want to revisit a point made in previous articles. For the first few years of training consistently, all strengths relate back to absolute strength. So by developing absolute strength, you will improve starting strength. You will also increase accelerative strength, strength-speed, speed-strength, yielding strength, reversal strength, and so on. You will improve performance, decrease injury risk and cure what ails you just by getting stronger. If you haven't gotten strong first, you're missing the boat. Developing starting strength is something you'll want to look at after you've exhausted all other lesser velocity training means.

Before moving along, I want to revisit a point made in previous articles. For the first few years of training consistently, all strengths relate back to absolute strength. So by developing absolute strength, you will improve starting strength. You will also increase accelerative strength, strength-speed, speed-strength, yielding strength, reversal strength, and so on. You will improve performance, decrease injury risk and cure what ails you just by getting stronger. If you haven't gotten strong first, you're missing the boat. Developing starting strength is something you'll want to look at after you've exhausted all other lesser velocity training means.

As you start training traits that are faster than absolute strength, they start to improve all of the traits that are to the right of them on the velocity continuum. What is the mechanism for this? To be completely honest, I don’t know. I've never seen a study on this, but hopefully I—or someone else—can get this figured out and publish the information on it. However, my speculation is that it is simply akin to improving absolute strength. We are seeing adaptations occur from this new stimulus. At some point, the body will adapt to that stimulus as fully as it can without directly or more closely training that exact trait. So when you add in a little higher velocity, it is more closely related to the next faster trait and you see great results again.

Some may think they can cheat the system and just jump directly to that trait. Unfortunately, this usually ends with poor results. The trait didn’t have the base underneath it to maintain improvements, and while spectacular, all the results are largely transient. As soon as you stop training that trait, it is gone. It may be that the lifter is unable to use appreciable loads for this velocity because his body hasn't adapted over time to progressively overload those other traits. It is akin to the man who built his house on sand. He didn't spent any time developing the proper foundation, and when the first storm blew in, the gains were lost.

I worry about strange injuries occurring as a result of this. If the corresponding tissues haven't improved in the other strengths, I'm afraid that weird injuries such as avulsion fractures and tendon and ligament ruptures would happen because the lifter didn't develop the high speed yielding strength that would have occurred from the other traits. Again, this is speculation based off evidence that I've seen from training athletes, not peer-reviewed research.

Most people go wrong when they get too advanced for the athlete's current status. They want to write programs for highly advanced trainees, but the trainees are essentially beginners or maybe intermediates.

So how would we develop starting strength? Well, we would need to use specialized exercises. I've only tried to develop starting strength in the lower body of athletes, so I won’t be mentioning anything in the upper body. To be able to achieve such high velocities, you have to either do a ballistic exercise or find another way to alter the acceleration/strength curve that exists. Realize that for a traditional bench or squat at submaximal loads, the bar spends far more time in deceleration than acceleration. For the bench press, it’s about 37 percent of the lift in acceleration and 63 percent of the lift in deceleration. Understanding this, there are ways to improve the time spent in acceleration, which would allow you to get to those higher velocities.

My favorite way is to do ultra high band tension squats with very low bar weight. For someone who is a 600-pound squatter, you're looking at two blues on each side as a starting point on an empty bar. This leads to a virtual load of about 445 pounds at the top and probably around 75–100 pounds in the bottom, depending on squat depth. If you examine the research, maximal and circa-maximal lifts have greater amounts of time spent in acceleration to continue to overcome their extreme relative inertia. By using the accommodating resistance, you take advantage of this by increasing the loads where the body would normally have to slow down. Because the additional resistance of the band is pulling you back down, you can actually accelerate more. You are then able to achieve those higher velocities because you're accelerating for a longer period, and the lighter load, especially in the bottom, allows the velocity to reach an even higher peak.

For the bar weight, I prefer to keep that on the very low end in the vicinity of about 10 percent. To be truthful, I never get out a calculator, but I do pay attention to the actual bar weight. If I start getting a load that is equivalent to another band, I put on another band. I always err on the side of too light and too fast because speed is the key.

What do I mean by equivalent of another band? Going back to the rough estimates that Dave or one of the other guys put out in an article in the late 90s or early 2000s, a strong band will be about 100 per band with a proper choke. An average band will be about 75 per band, a light band will be about 50 per band, and a mini will be about 25 per band. So essentially, if I start to get up to the point where the bar load increases to 25s (about 95 pounds), I add on the next band up. Is that scientific? No. But it works. I know that.

Now, you may have noticed that this article deviates a little from the citations I usually use. Because this is a highly advanced technique, there aren’t many people who would be ready for it. In all truthfulness, I can count on my fingers how many athletes I've used this with, and to be brutally honest with myself, I can count on one hand how many of those who did it were actually ready for it. For me, I don’t know if it would be possible to get a critical mass necessary for a publication to look at the proper implementation of this. Until then, we will have to rely on the texts of those like Bondarchuk who have had the opportunity to work with the 0.1 percent of the elite.

References

- Bondarchuk Anatoly (2014) The Olympian Manual for Strength & Size: Blueprint from the World’s Greatest Coach. Ultimate Athlete Concepts.

And you know what the crux of it was? The program I did the year before that had APRE on squat, bench, and trap bar deadlift, some weighted jumps, traditional plyos, and a ton of posterior chain actually saw better results on improved vertical jump, sprint speed, and change of direction. I got away from the basics, and I got away from results.