Christmas is approaching on a cold and still night. I'm sitting at my kitchen table under a cone shaped light. My kids are in bed, and I exhale after a day of work. My iPhone dings with a message from one of our coaches wanting to introduce me to one of his player's parents who needs advice. I oblige and ask the parent to call me.

Chasing the Athletic Edge

This is almost a weekly occurrence. Parents frequently ask for lifting, running, or nutritional recommendations to give their kid an edge. My nutritional guidance is generic because I am not an RD. I do not like sharing lifting advice for student-athletes who I am not working with privately, but running programs are easy to prescribe.

Student-athletes feel it's necessary to train year-round, emulating Ronaldo's or Messi's TV ads at every workout where they're dripping sweat and succumbing to exhaustion. The elite youth soccer environment revolves around promises of scholarships and media—everyone adhering to more is better.

We've pushed our kids into an ultra-competitive environment where student-athletes no longer have a true off-season.

It is a common fact that no time off may lead to overuse injuries like runner's knee, Achilles' tendonitis, shin splints, and plantar fasciitis (5). Many student-athletes never have a chance to rest, heal, try other sports, cross-train, or be kids. The ones that could use the off-season to focus on building specific attributes like strength or speed typically don't have sufficient time to do so.

Yearly Breakdown for Student-Athletes

From a soccer and conditioning standpoint, we provide our athletes with high-level coaching and year-round fitness programming. They receive adequate, age-appropriate training for long-term soccer and athletic development. While there is certainly room for a better strength training protocol, we provide everyone with the means to become more efficient in bodyweight strength training basics that include but are not limited to the squat, hip hinge, and push-up.

Our club consists of six girl teams and six boy teams ranging in ages from 13 to 18 years old. We have over 240 student-athletes. The year looks like this for our players:

Fall (September – Mid-December)

- In-season

- Private school kids also play high school

- Periodic double header weekends (Saturday and Sunday games) with a minimum of one game per week

- Three days of training per week

Winter (3 weeks)

- Two college showcase tournaments (three games in a weekend)

- Indoor or futsal leagues/training

Spring (Mid-January – June)

- In-season

- Public school kids also play high school

- Periodic double header weekends (Saturday and Sunday games) with a minimum of one game per week

- Three days of training per week

Summer (July – August)

- Two college showcase tournaments (three games in a weekend)

- College ID camps (between one and three on average per player)

- Local soccer camps

The schedule is robust but manageable, right?

Imagine you're a kid navigating the aforementioned program while working with a private trainer for soccer skills development and playing other sports. Let's add additional time with other coaches or tutors for weightlifting, second languages, homework, or after-school activities. In some situations, you may also need to complete extra running because a coach deviated from the periodization design or said you're not fit enough.

Speaking purely from observation, we are in no danger of overtraining syndrome.

Kids are resilient, and there are natural breaks they do receive where they can get additional rest such as family vacations or weather cancellations (snow or excessive heat).

I appreciate the desire to work, but not everyone works efficiently to balance all their activities. Balance prevents overuse injuries and can build weaknesses instead of training everything year-round.

This is the current climate in elite youth soccer. The machine is big, and the beliefs run too deep for anyone to make instantaneous changes.

Parents always want more for their buck. Colleges want ID camp money. Local soccer clubs run camps for additional income. Leagues want tournament dollars while personal trainers advertise by convincing athletes/parents they need their services. Skills coaches also want a piece of the pie.

Not knowing what they need and don't, kids assume they need it all!

There is a lack of strength training presence in youth organizations across the country. I studied exercise science at Virginia Commonwealth University, earning my CSCS in 2013 and maintaining it throughout my 10-year professional soccer career. As my own guinea pig, I bounce ideas and beliefs off strength coaches, physical therapists, athletic trainers, and orthopedists as I continue to read and study.

Protocols for Athlete Injury Prevention

My experience enables me to evaluate and recommend periodization and injury prevention protocols for our athletes.

Student-athletes and parents need to realize a couple of things. From the time they are pre-teens until their junior or sometimes senior year, their bodies are growing at a tremendous rate.

They are at risk for conditions like the aforementioned overuse injuries related to their growth and training habits.

Unless you are at a national team caliber, colleges won't recruit you until your sophomore year of high school. Most programs won't even seriously consider players until their junior year. There is plenty of time from 12 until 17 to improve. And if the athlete doesn't want it as bad as some of these parents, guess what? It is not worth the time or money.

I can't keep kids from using unqualified personal trainers. These are people who do not take into consideration all the activities kids are involved in, adjust for physical asymmetries, introduce injury prevention protocols, or can effectively periodize a student-athlete's training away from the field.

We can try to influence and educate players, parents, and coaches when the opportunity presents itself. Since the majority of the athlete's time is with us, I want to cultivate an environment that adjusts for all the extra-curriculars the players have going on.

Youth Soccer Conditioning Program

Before I arrived in 2019, our coaches used Raymond Verheijen's book on soccer periodization (Original Guide to Football Periodisation Part1).

Raymond works with professional soccer players at the elite level in Holland. There are some cool concepts you can pull from his work.

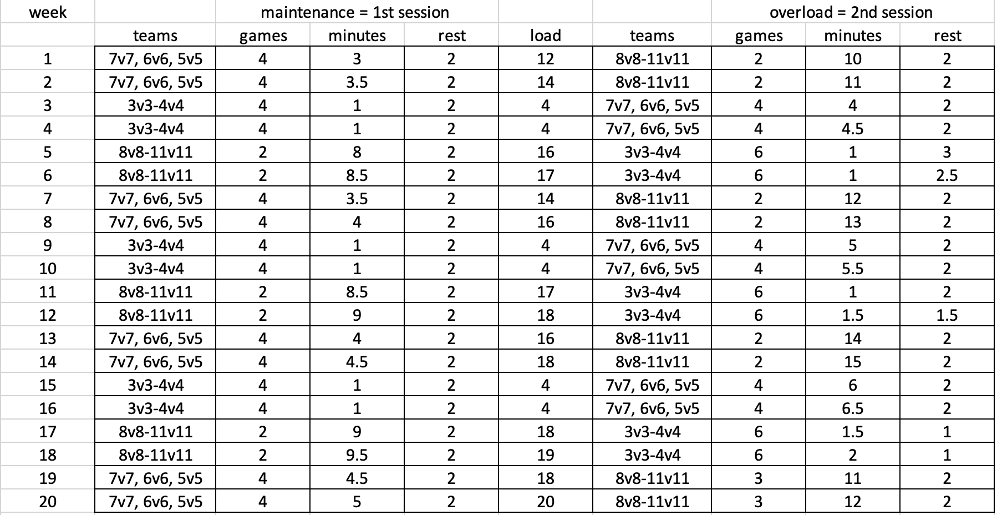

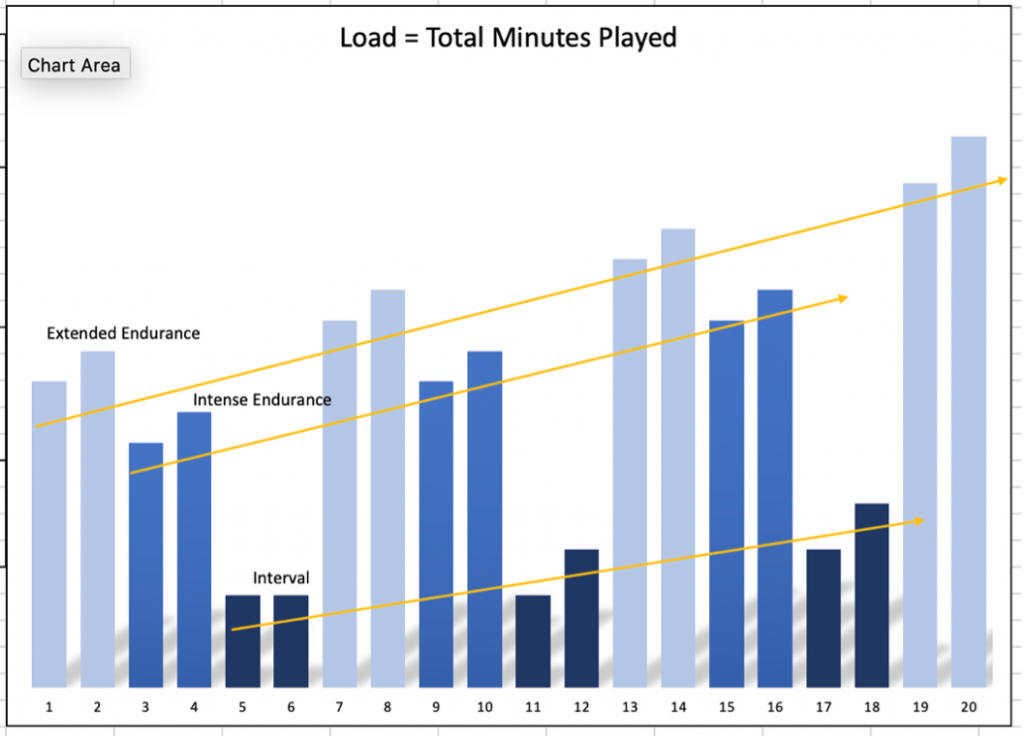

Because we loved his concepts in fitness through play, I adapted the periodization for teenagers and pre-teens. The field sizes and numbers of players in training exercises cycle between training lengths and rest times to achieve different fitness goals. Smaller fields of 3v3 or 4v4 are more intense and require shorter, repetitive sprinting with less rest. A larger field with 9v9 or 11v11 requires more sub-maximal efforts between brief intense actions. We also play with 5v5 and 7v7 variations.

Football Fitness Through Play

Through this method, we can achieve football fitness by playing our sport. Athletes naturally address their cardiovascular fitness through this method of training in combination with weekend games. I look to the value of sprinting for our additional conditioning work. I program a few minutes of sprints at the end of training Day 1 and Day 2, leaving Day 3 for recovery and tactical preparations for the weekend. Sprints cycle between longer sprints and more rest with shorter sprints and less rest.

Sprinting at the end of practice achieves a couple of things:

- Mental toughness, because max effort runs at the end of training, are difficult.

- Competition—no one wants to be last.

- It forces the smart, skilled, or lazier players to do work. Skilled players can find ways to pace themselves in training by relying more on their skills in team training exercises.

- Adds higher intensity runs to compensate for any potential lack of adequate training space. This is a common issue for some youth soccer clubs.

Strength Work

Our strength work is micro-dosed into the warm-ups. Every kid has a Thera-band they use in warm-ups to activate and strengthen their hips. We do variations with on-field lunges, squats, hip bridges, and planks because we don't have a weight room.

We use bodyweight exercises to achieve our strength goals and prevent injury. I created an instructional YouTube video and passed it along to all the teams and players, giving the captains the responsibility of carrying out the exercises.

Bodyweight training teaches athletes to use their own bodies relative to their size and ability. Without load, they are less likely to hurt themselves if I am not there to correct form. Single leg movements additionally introduce different levels of stability training that has shown to decrease lower limb injuries (3, 4).

Student-athletes can benefit from being taught how to properly squat, hinge, and perform a push-up for later carry over into the weight room. When they become proficient in these movements, I am happy to introduce them to a qualified strength coach in our area.

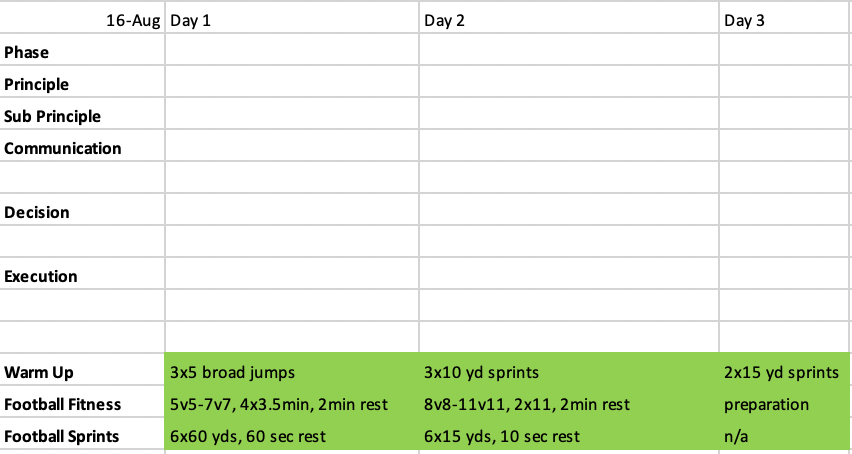

Below is just one example from our periodization folder. The head coaches use the Phase through Execution to address their team session goals. I go in and prescribe the Warm-up, Football Fitness, and Football Sprints in green:

As I mentioned, the kids already know the strength and stability work from my YouTube video. I will sometimes apply it myself if I am with their team on that day. The video also has instructions for various warm-up movements in horizontal and lateral planes, including skipping, lateral shuffles, karaoka, backpedal, backward skipping, skipping for height, high knees, and butt kickers. I like to throw in some broad jumps because the exercise requires full triple extension, or we use sprints to activate the nervous system to prepare athletes for training.

Football Fitness is the portion coaches use as their guide to achieve conditioning within their sessions. In this example, on Day 1, they are to perform 5v5 or 7v7 (depending on their numbers for training that night) for 4 sets of 3.5 minutes with 2 minutes of rest between bouts.

In this example, Day 1 uses a shorter duration of exercise with more frequent sprinting on a medium size field. Day 2 calls for a longer duration of exercise with less frequent sprinting on a larger field.

High-Intensity Short Sprinting

Our third option includes repetitive, high-intensity short sprinting, and little rest between intense bouts from a 3v3 or 4v4 game on a small field. The field sizes correlate with the number of players. Coaches know approximately what those are, so I have not plugged in those parameters.

In the example, Day 1 is a maintenance day for the Football Fitness with an overload on sprinting (using total sprint distance as our measure for load).

Day 2 is an overload on Football Fitness because we extended playing times but kept the total sprint distance shorter. Day 3 is always for game preparation, allowing for a deload and coaches to organize tactically for the weekend. Each week the three focuses will rotate so that one will be applied on Day 1 under maintenance and the other on Day 2 as an overload.

The Football Fitness looks like this (load = total minutes played):

The graph below depicts Day 2 (aka the second session). We create overload by extending playing times:

Football Sprints are applied after training. Application is self-explanatory and previously discussed.

I have them running longer distances on Day 1 with more rest. Day 2 is shorter distances with less rest. This variation challenges athletes with a different stimulus each night. As the season progresses, we slowly add in more repetitions. The main goals are, again: mental toughness, competition, and concentrated sprinting.

Conclusion

This model is simple and easy to follow. Head coaches don't want fluff and often don't care about the science. A program like this is easy for anyone to reference quickly and complete without much instruction. Without a weight room, time, funds for additional staffing, and expensive technologies, we routinely challenge our methods to improve injury prevention and performance.

The elite youth soccer environment needs a change. To combat deep seeded beliefs surrounding soccer fitness, education is key to teaching parents, players, and coaches.

The more people we connect with, the more people will seek out our advice. Controlling our environment while considering all the extracurriculars our athletes are involved in is our best option for assuring balance, lower injury risk, and safely improving the performance of our athletes.

References

- Andrzejewski, Marcin, et al. "Sprinting Activities and Distances Covered by Top level Europa League Soccer Players." International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching. February 2015, 10(1):39-50.

- Andrzejewski, Marcin, et al. "Analysis of Sprinting Activities of Professional Soccer Players." PubMed. August 2013, (8):2134-40.

- Dawson, Samuel, et al. "Improving Single-Legged–Squat Performance: Comparing 2 Training Methods with Potential Implications for Injury Prevention. PubMed. September 2015, 50(9): 921–929.

- Palmer, Thomas. “Single-Leg Balance Training: An Intervention Tool in the Reduction of Injuries.” Human Kinetic Journals. Volume 12, Issue 5, pages 26-30.

- The Five Most Common Overuse Injuries. Southeast Orthopedist Specialists. https://se-ortho.com/common-overuse-injuries/

Header image credit: stockbroker © 123rf.com

Andrew Dykstra played men's soccer for Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia, earning his BS in Exercise Science (2008) and MS in Sports Leadership (2010). He played professional soccer for 10 years in Major League Soccer (Chicago Fire 2009-2010, Charleston Battery 2011, DC United 2012-2016, Sporting KC 2017-2018, and Colorado Rapids 2018). After retiring, he became the Director of Goalkeeping and Director of Sports Performance for Virginia Development Academy in Woodbridge, VA. Andrew is responsible for the conditioning periodization and injury prevention protocol for over 290 soccer players (7 boys teams, 7 girls teams) ranging in ages from 13 to 23 years old. He holds his CSCS (since 2013).

Love the breakdown of how you wave your running volume.