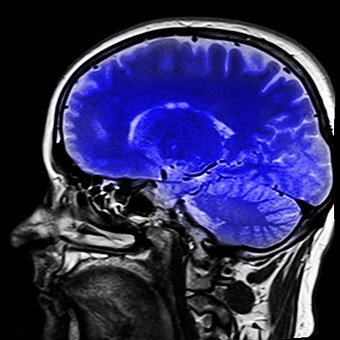

The negative health consequences of obesity are well documented, but new research from the Medical College of Georgia suggests it does more than just damage your body. It can change your brain.

In a study published in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, neuroscientist Dr. Alexis Stranahan looked at the effects of a high-fat diet on normal male mice split into two groups. The first group of mice ate 10 percent of their calories from saturated fat. The second group of mice ingested 60 percent of their calories in the form of saturated fat. Other factors, such as macronutirents and protein, were kept similar to limit variables. The diets of the mice being studied were relative to a healthy diet in humans versus a diet high in fast food.

Researchers took metabolic measurements at four, eight and 12 weeks. They also measured synaptic markers at these times to measure brain activity in the hippocampus. Although measurements were similar at four weeks, changes began to take place during week eight. The mice had normal brain activity, but were fatter than their counterparts on a low-fat diet. At 12 weeks, the mice on a high-fat diet started showing a reduction in synaptic markers, signaling a shift in the way the brain’s microglia were working.

In a healthy brain, microglia serve as the garbage men, picking up trash and infectious agents. This keeps neurons healthy and cognitive ability at optimal capacity.

“Normally in the brain, microglia are constantly moving around,” Stranahan said. “They are always moving around their little fingers and processes. What happens in obesity is they stop moving.”

The changes in the microglia also changed brain function.

“[The microglia] basically just sit there and start eating synapses,” Stranahan said. “When microglia start eating synapses, the mice don't learn as effectively.”

Although the results are significant, researchers believe the effects can be mitigated with dietary improvement. After 12 weeks, half of the mice on the high-fat diet were switched to the low-fat diet. It took two months for the mice to return to normal and a larger fat pad remained, making it easier for those mice to regain weight in the future, but brain function improved.

“The good news is going back on a low-fat diet for just two months, at least in mice, reverses this trend of shrinking cognitive ability as weight begins to normalize,” Stranahan said.

For the mice who remained on a high-fat diet, their brain function continued to be impaired as synapse counts decreased.

“Microglia eating synapses is contributing to synapse loss and cognitive impairment in obesity,” Stranahan said. “On the one hand, that is very scary, but it's also reversible, meaning that if you go back on a low-fat diet that does not even completely wipe out the adiposity, you can completely reverse these cellular processes in the brain and maintain cognition.”

The results also showed elevated inflammatory cytokines and tumor necrosis factor alpha in the brains of the fat mice. For this reason, researchers also believe existing drugs for inflammation may be able to be repurposed to help with brain health.

Header image via Pixabay