The concept of tonic and phasic muscles is not new. It has been most popularized by Dr. Vladimir Janda and his joint by joint theory. Both are similar in some respects but differ as well. The joint by joint approach refers to the body’s natural tendencies to give joints a main purpose. A joint is either stable or mobile — few have both. All the joints should work synergistically by performing their function and allowing the joints above or below to do their job. The tonic and phasic muscle concept is similar.

The Tonic and Phasic Muscle Concept

When we look at the body as a system, it is regulated by the big guy upstairs: the brain. It is important to understand that our neurological system (our brain) dictates heavily which muscles act passively or actively. Our neurological system is complex but can also be tricked (keep this in mind for later). Tonic Muscles These muscles operate on a rhythmic level and often dictate our body’s posture — or a better word would be position. These muscles are developed first in the womb and remain dominant throughout our developmental years as babies. Unfortunately, we didn’t have a choice in the matter, as our neurological system forced these adaptations to occur by sticking us in the womb in a fetal position. That is why this position, regardless of age, feels natural, comfortable, and like an optimal sleeping position (wink, wink). Now, it may seem that because these muscles were developed first that they are stronger, but it is a false sense of strength. We call this a neurological tightness: a tightness of a muscle that forces a change to position (posture) or function is said to be neurologically tight. Try stretching this for years and years and you’re just pissing in the wind. These muscles often include the following:

Now, it may seem that because these muscles were developed first that they are stronger, but it is a false sense of strength. We call this a neurological tightness: a tightness of a muscle that forces a change to position (posture) or function is said to be neurologically tight. Try stretching this for years and years and you’re just pissing in the wind. These muscles often include the following: - Pecs (internally rotated shoulder girdle)

- Biceps Brachii (anterior shoulder pain)

- Upper Trapezius (poor overhead movement and shoulder function)

- Quadratus Lumborum (QL)

- Piriformis (tight glutes)

- Psoas (lumbar extension)

- Hamstrings (pelvic tilt)

- TFL (glute inhibition)

- Gastrocnemius (loss of dorsiflexion)

- Mid and Lower Trap (better overhead shoulder movement)

- Rhomboids (scapular stability)

- Serratus Anterior (proper shoulder mechanics)

- Triceps (optimal elbow position)

- Rectus Abdominis and Transverse Abdominis (optimal spinal health, breathing function and force production)

- Glutes (low back health and hip function)

- Vastus Medialis (knee tracking and glute function {by establishing knee position})

- Tibialis Anterior (dorsiflexion)

Training Considerations

Our main job as trainers, strength and conditioning coaches, physical therapists, and movement specialists (still not sure what that is) is to dictate training. Volume, load, intensity, programming, and specificity are essential parts of a good training program. Unfortunately, not all of us are equipped with all the knowledge to make the best decisions, so let’s look at some training considerations. Often, in powerlifting, we prescribe a training ratio that favors the anterior chain. This means training the glutes, hamstrings, erectors, traps, and pecs (anterior) more because we often think these muscles are weaker. We think these muscles are weaker because most people are anterior dominant (quad) and we tend to train more of what we can see. If you remember from earlier, tonic muscles are often over-tight and pull us into a position (posture) that will offer greater stability. This is based on the perception of your brain — you might not even feel it. How you will know is when you start experiencing small nagging injuries continuously. So, the question of the hour is:“If certain muscles are pulling us into positions of false stability (neurological tightness) why do we dictate our training to exacerbate it?”The answer is simple: we think it’s right. Take a 300-plus-pound powerlifter who is used to training in the same position, with the same “stable” posture. Load him, move him a half-inch to the left, right, front, or back, and what happens? I’ll tell you what happens: injury. There is no true stability. It’s false. So how do we alter our training to improve this? I say “improve” because fixing it is not the answer. We do want some neurological tightness, but we don’t want to rely on it.

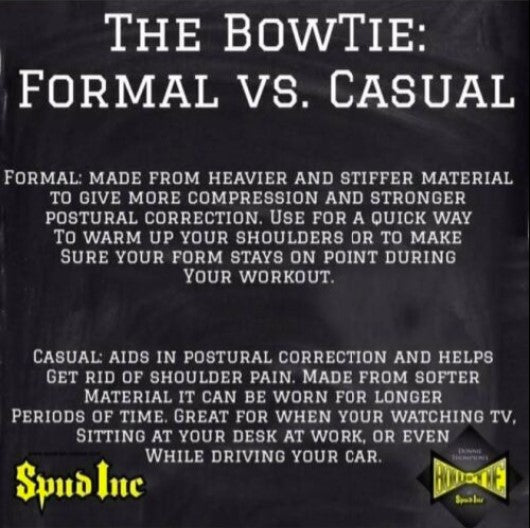

Tonic Training Considerations

Volume — In this instance, we don’t want to alter volume too much. Decreasing volume does have a propensity to decrease muscle size, and for some of us, this is not an option. Keep the volume the same, decrease slightly, or change frequency. Load — This will have one of the biggest impacts. When the load is great enough, a threat is perceived and the tonic tissues create stability. If we can decrease the load slightly and still elicit a training effect, we can decrease this perception. This is more focused towards accessory movements and not the big three. Intensity — This is the second part of the equation. When we go crazy on intensity, we jack up the wrong part of the central nervous system. It puts us in a fight-or-flight state and we again find ourselves in a mode of protection, which is essentially tightness. Create enough intensity to complete the movement and hit your desired sets and reps. No more is needed. It’s a waste of energy and it does more harm than good. Programming — This isn’t a block of training that should have a long-term focus. It should, however, be long enough to make a change, and is more suitable for off-season or your non-competitive season. The severity of the situation will differ the length of time needed to make the necessary corrections.

Phasic Training Considerations

For the phasic muscle training considerations, we basically want to do the opposite of the tonic considerations. You still want to balance your training regarding training volume, recovery, progressions, etc., but these should have more of a focus. One of the biggest staples in phasic training is stability — not stability as in standing on a BOSU ball or some dumb shit like that, but increasing the stability of the joint by using the phasic muscles listed previously. For example:- Training the middle and lower trapezius using exercises such as the YTL will offer greater stability to the scapula and lead to better shoulder health. This will also decrease the body’s need to neurologically tighten the upper traps for overhead movements.

- Training the rectus abdominis and transverse abdominis via anti-rotation, breathing, and bracing exercises will allow the tonic spinal erectors and hamstrings to down-regulate and you can then alter position.

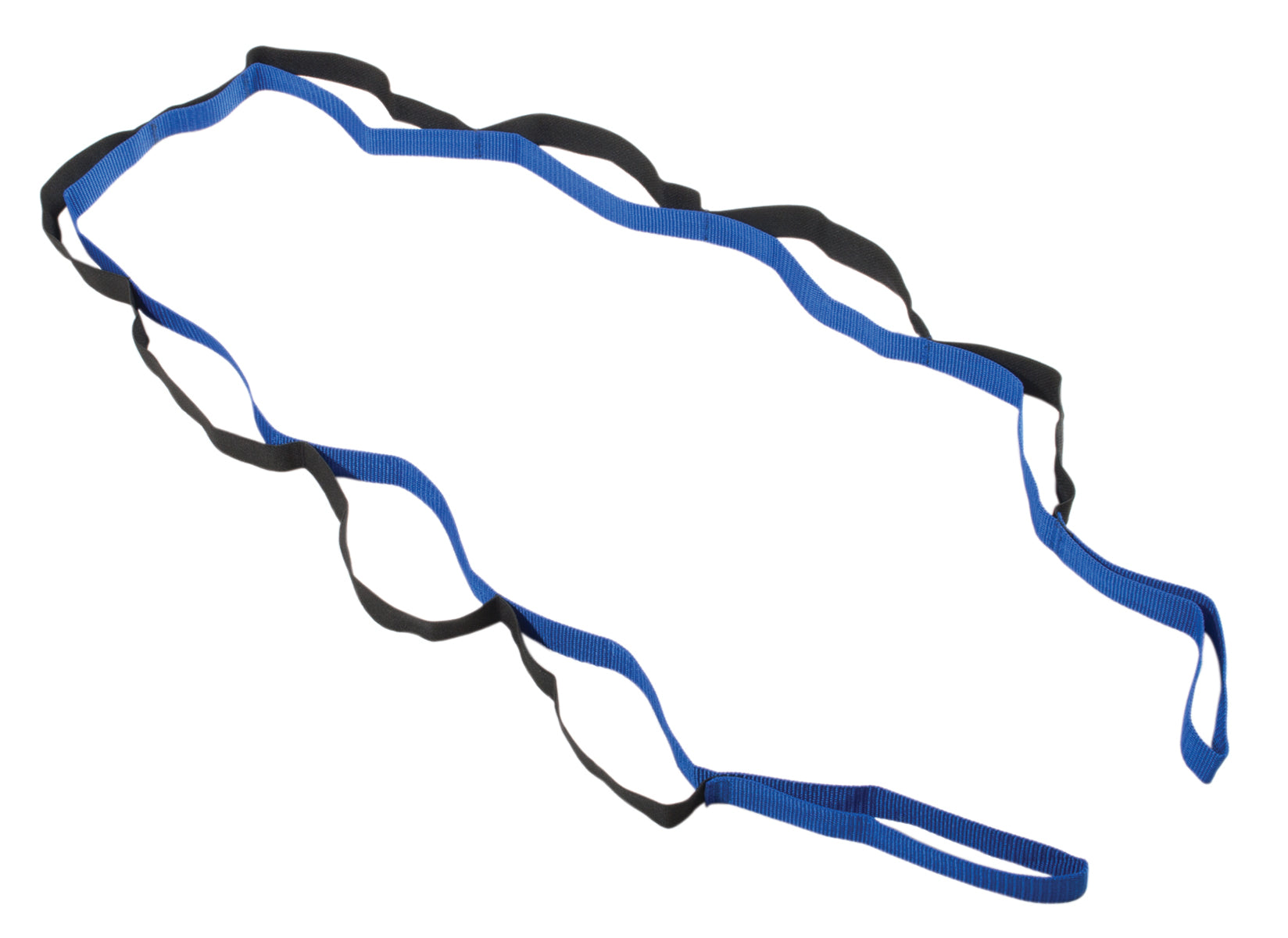

Image credit: bestdesign36 © 123rf.com

Loaded Carries for Improved Body Position and Health